The emperors made us speak one language to bring us together. It failed, but it also succeeded.

Participants of the Great Ethiopian Run wear a t-shirt with the message “Empower Women, Empower a Nation” in Amharic on the back. Credit: UNICEF Ethiopia/2014/Sewunet.

This is the fifth article in the seven-part series Living In Translation about language and identity. They are guest edited by Nanjala Nyabola and will be published across this week. See all the articles published so far here.

Like most African nations, Ethiopia brims with difference and diversity. Among our 100 million people, we have around 80 ethnic groups and nearly a hundred languages. These variations in identity form the centre around which much of today’s politics revolve. Ethiopia’s controversial federal structure is just one example of its attempt to recognise complex internal differences while remaining united.

And yet, among all this swirling diversity, one particular language has come to dominate this complex country. Although the Amhara are just one of Ethiopia’s myriad ethnic groups – and only the second largest, accounting for 27% of the population in the 2007 census – Amharic has become the country’s official language. (This is a rarity in Africa, where most official languages are that of the former coloniser.)

Across Ethiopia, regional governments may use different languages appropriate to their constituencies, but the federal government operates in Amharic. The vast majority of the population speaks Amharic, either as a first or second language. The nation’s working language in commerce is Amharic.

How did this language – considered by some scholars to be Africa’s most advanced – come to be so widely used? What does it mean that this tongue – adopted from the ancient Ethiopian language of Ge’ez – has become the country’s official mode of communication? How does the use of this distinctly northern language – with its unique fidel script made up of 33 characters, each with seven forms depending on the vowel sound – affect questions of identity in Ethiopia?

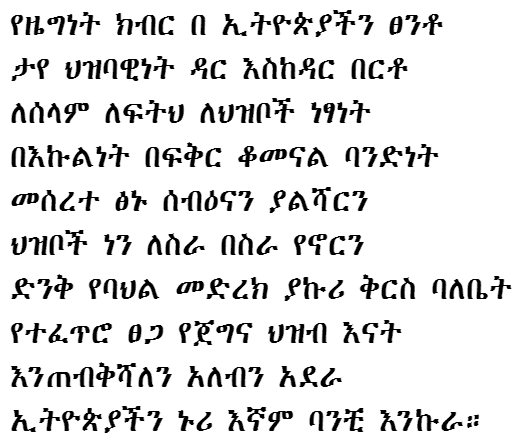

The lyrics to Ethiopia’s national anthem in Amharic.

Amharic has been used in official circles since the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty in 1270, but it was the actions of various emperors in the 19th and 20th centuries that gave the language the significance it has today. In different ways, they used Amharic as a way to help unite their diverse empires.

Teweodros II (1855-1868) was the first to make Amharic a literary language, elevating it into written form. He ensured his royal chronicles were written in Amharic rather than Ge’ez like those of his predecessors. Yohanes IV (1872-89) followed his lead, using Amharic in his correspondence with regional kings; although a Tigrigna-speaker himself, he believed Amharic could help unify the state. Minilik (1889-1913) then further spread the language as he expanded his territory, incorporating new ethnic groups and local elites into his power structures as he went along. Under him, Amharic became the language of Ethiopia’s rulers.

It was Emperor Haile Selassie (1930-1974), however, who declared Amharic Ethiopia’s official language. He came up with a legal framework and language policy with aim of easing communication across the empire’s myriad linguistic groups. While Minilik had focused on making Amharic the mode of communication among the elites, Haile Selassie targeted the general population. During this reign, Amharic was the only language used in primary schools and for government activities.

The ideology behind the policy was to create a centralised homogenous state. Amharic was treated as a symbol of unity, and language was utilised as a tool for nation-building. Many, however, criticised the way in which it forced people to assimilate. They felt alienated by the favouring of one Ethiopian language above all the nation’s vast array of others.

Today in Ethiopia, the legacy of this history lives on. Amharic has become the country’s lingua franca and one has to master it to climb the political ladder. The language dominates politics, education and the media. It is generally perceived to have more prestige than other local tongues.

Among other things, the spread of Amharic has also facilitated the diffusion of northern culture to other parts of Ethiopia. Language is intrinsic to identity and, to some extent, Ethiopian-ness has become closely associated with the culture of the north, where the Amhara and Tigray regions are located.

Language also remains a deeply political subject. Because modern Ethiopia was created through territorial expansion and subjugation, questions of ethnicity and language remain central to today’s political discourse. In the 1960s, the student movement that opposed the government was driven by grievances over nationality as well as land.

Although the exact relations between Ethiopia’s many ethnic groups have shifted significantly over time, many historical and fundamental questions about identity in the country are still yet to be resolved. For many, the legacy of the empire’s Ethiopianisation – or, as some call it, Amharanisation – needs to be re-examined and addressed.

The history of Amharic is thus highly complex and contested. The fact that Amharic was imposed on the people by elites from one particular group is well-known and keenly-felt among Ethiopians. This plays into feelings of marginalisation and emphasises the divisions within the diverse population.

And yet, at the very same time, there is the inescapable fact that Amharic does bind Ethiopian society together as the emperors had envisaged. Its widespread use does allow people from across the vast nation to communicate easily. It is telling irony – and one that encapsulates Ethiopia’s historic uniqueness and contradictions – that even those who decry the dominance of Amharic today must do so in Amharic if they are to reach many of their compatriots.

Nanjala will be doing a twitter chat from the African Arguments handle on Thursday 9 May at 10am GMT (i.e. 11am West Africa standard time; 12pm Central Africa Time; 1pm East Africa Time). Chat to her and ask her about all things language and identity using the hashtag #LivingInTranslation.