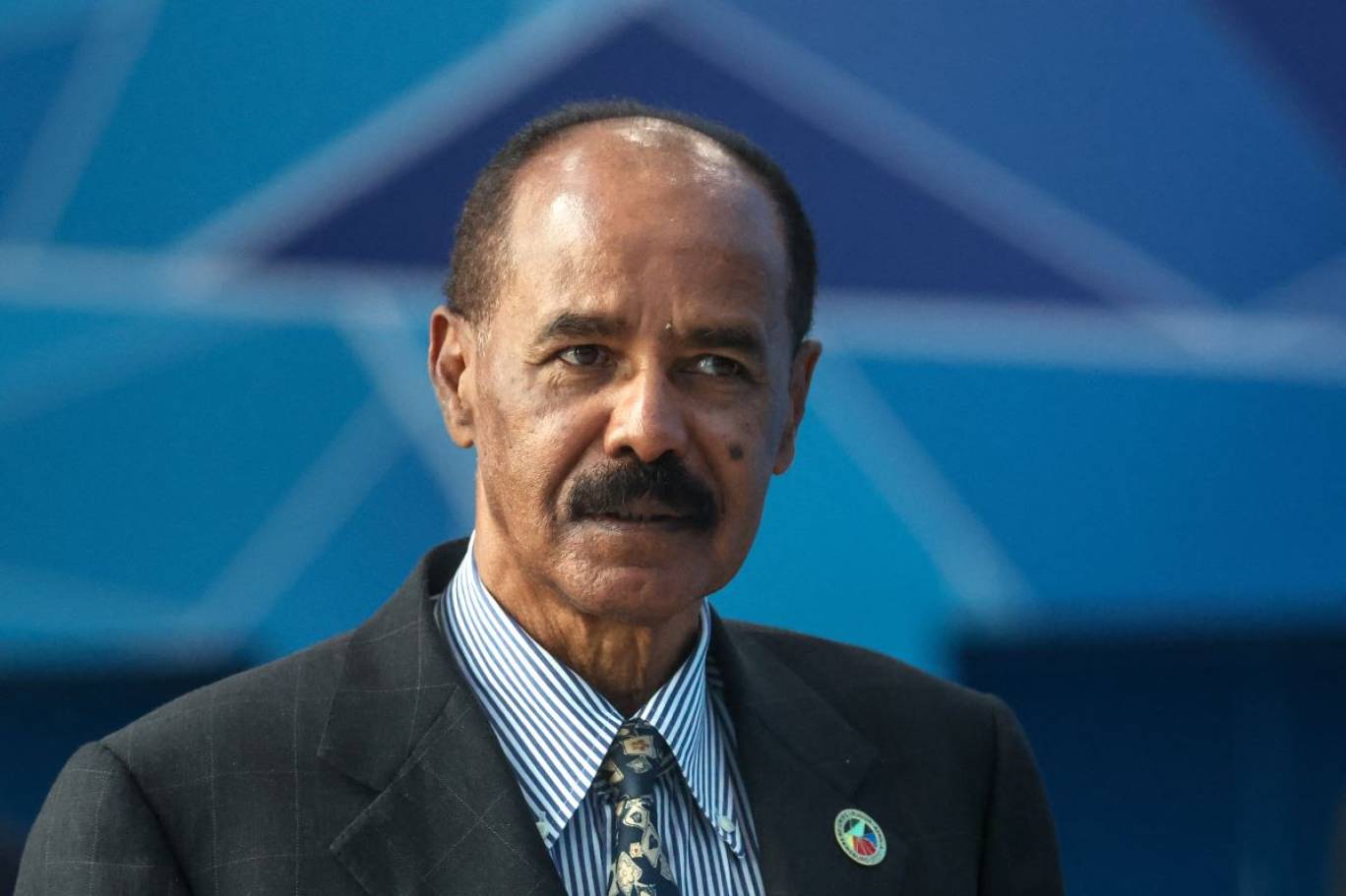

This Saudi vision aligns with a clear Eritrean understanding of the opportunities presented by the current regional situation. Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, known for his cautious policies, recognizes that the growing Sudanese vacuum could become a threat to his country's border security, whether through increasing Ethiopian pressure or through the expanding smuggling and arms trafficking routes that accompany the disintegration of the Sudanese state. Therefore, he is actively working to build an undeclared tripartite axis linking Asmara with Riyadh and Cairo, in response to the rise of Ethiopian influence and Addis Ababa's desire to redraw its spheres of influence in the highlands and the Red Sea.

Afwerki's visit to Cairo came at a sensitive time, coinciding with indications of Ethiopia's desire to secure a sea outlet by any means possible, whether through economic agreements, political bargaining, or security deals. Egypt understands that any Ethiopian maritime arrangements would disrupt the historical balance in the region, not only because of their connection to the Nile water issue, but also because any Ethiopian expansion in the Red Sea could reshape the balance of power between the Arab and African shores.

Hence, Cairo's hosting of Afwerki was part of a joint strategy with Asmara to contain Ethiopian influence and protect Red Sea waterways from politicization or use as tools of pressure. European and American research centers indicate that Cairo is coordinating with Asmara to prevent the creation of new power balances that exclude traditional transit countries, particularly Sudan, which is experiencing political paralysis that renders it less capable of defending its maritime or land interests.

This tripartite Egyptian-Saudi-Eritrean initiative coincides with the African Union and IGAD's sponsorship of an agreement between the Ethiopian government and some Amhara factions—an agreement lacking representation and replicating the Tigray scenario, albeit under a different political guise. The Ethiopian model for conflict management relies on producing superficial agreements signed in the name of the factions, while their social and military bases reject them. This allows Addis Ababa to reshape the conflict to its advantage and creates disrepresented adversaries that can be dealt with without political cost.

According to the Ethiopian context and the experiences stemming from it, this agreement serves two objectives: the first is internal, which is to fragment the power of the Amhara Fano militias and ensure their inability to threaten the center of power, and the second is external, which is related to giving Ethiopia a greater margin for bargaining with Sudan and Eritrea, and turning all Amhara tensions into leverage against Cairo and Riyadh by opening border files with Sudan and linking them to the issue of influence in the Red Sea.

The impact of this agreement extends beyond Ethiopia's borders, as the resulting instability spills directly into eastern Sudan, where supply lines expand, smuggling operations are facilitated, and the influx of mercenaries increases, all amidst the collapse of the Sudanese security apparatus. Furthermore, Eritrea views this agreement as an attempt to marginalize its regional role within the Ethiopian highlands by creating artificial political realities under the auspices of IGAD and the African Union—realities that could become a direct threat to its national security. This is compounded by Sudan's absence from influencing current developments, despite its geographical location and political history, because it lacks the administrative capacity to translate these resources into influence.

Over the years, the lack of centralized decision-making and the multiplicity of power centers have eroded Sudan's position within the Red Sea system, allowing Eritrea to easily advance regionally and subsequently build and solidify significant international influence. This is particularly true given Asmara's integrated strategy: expanding coordination with Khartoum when border stability benefits it, deepening cooperation with Riyadh on maritime security issues, and re-establishing ties with Cairo to counterbalance Ethiopian influence. Afwerki's movements, from Port Sudan to Cairo and Riyadh, demonstrate that he is building continuity and sustainability in his interactions with these capitals, rather than engaging in sporadic visits.

In summary, the rapid pace of regional developments reveals that Eritrea is operating within a clearly defined strategy, while Sudan is operating within an increasingly widening strategic vacuum. Eritrea possesses a clear objective, consistent decision-making, and a deep understanding of regional power dynamics, while Sudan possesses the geography but lacks the institutional will to utilize it effectively. While Eritrea is building cohesive networks of cooperation with Riyadh and Cairo and cautiously confronting Ethiopian expansionism, Sudan remains incapable of formulating an independent approach that defines its priorities and ensures it does not become an open arena for others' conflicts.

The overall regional landscape indicates that the Red Sea is entering a phase that will not wait for those who hesitate. Powers that define their position early will secure their share in the arrangements of the coming decade, while those that remain captive to their internal crises will have their position imposed upon them by others according to their own perceptions and interests.