Data Cutoff: April 11, 2024, at 10 a.m.

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here. Follow CTP on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

- Niger. A pro-Russian and Wagner Group–linked African outlet claimed that Russian Africa Corps soldiers will “soon” deploy to Niger, supporting CTP’s previous assessment that the Nigerien junta may contract Russian soldiers to help fill the gaps left by French and potentially US forces and address the country’s deteriorating security situation. Niger’s engagement with Russia in late 2023 and 2024 shares similarities with Burkina Faso’s engagement with Russia months before Africa Corps deployed to Burkina Faso. Russian forces in Africa have been ineffective in counterinsurgency operations and would likely be more focused on advancing the Kremlin’s strategic aims in Niger, such as securing access to valuable natural resources, destabilizing Europe, and consolidating Russia’s position in Africa.

- Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has increased its rate of attacks in western Niger since the beginning of 2024, likely to establish new support zones that it can use to facilitate more regular and severe attacks on critical roads connecting Niamey and various district capitals. The group likely already established a new support zone southwest of Niamey toward the end of 2023 that it is using to support its current attack campaigns.

- Horn of Africa. Ethiopia is continuing to advance bilateral partnerships with de facto autonomous regions of northern Somalia, which is exacerbating tensions between the SFG and Ethiopia by undermining the Somali Federal Government’s (SFG) claim to legitimacy and sovereignty in these areas. The overlapping domestic and regional crises with Ethiopia and its northern regions have weakened the SFG’s counterterrorism efforts by distracting the SFG and weakening cooperation with key security partners Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

- Somalia. Al Qaeda’s Somali affiliate al Shabaab launched a complex attack targeting a district capital in south-central Somalia, underscoring al Shabaab’s ongoing resurgence in areas that Somali forces liberated during the 2022 central Somalia clan uprising and counterterrorism offensive. The group had not conducted an attack of this scale in the western half of the Middle Shabelle district since September 2023, when it launched an offensive to reestablish itself in the area. Al Shabaab will continue threatening to reestablish a foothold in the Middle Shabelle region through its control of the west bank of the Shabelle River.

Assessments:

Niger

Author: Liam Karr

A pro-Russian and Wagner-linked African outlet claimed that Russian Africa Corps soldiers will “soon” deploy to Niger. Cameroon-based Afrique Media, citing unnamed military sources, reported on April 10 that an Africa Corps contingent will arrive in Niger.[1] The Russian Ministry of Defense set up the Africa Corps in mid-2023 to establish new footholds in the Sahel and subsume preexisting Wagner Group operations in Africa.[2] Afrique Media has strong ties to the late Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin and Wagner Group personnel that have since signed contracts with the Russian Ministry of Defense, indicating it could have legitimate sources to support the report.[3]

CTP previously assessed that the Nigerien junta may contract Russian soldiers to help fill the capacity gaps left by French and potentially US forces and address the country’s deteriorating security situation.[4] The Nigerien junta initially showed interest in a Wagner Group deployment in its first days in power, when it faced a potential regional invasion to restore democratic rule.[5] The junta has met with Russian defense officials linked to Russian military personnel in Africa since the threat of invasion ended and signed several unspecified defense agreements in December and January.[6] US officials have also voiced concerns about growing Nigerien military cooperation with Russia in 2024, and they gave broad public warnings to regional states to avoid collaborating with Russian mercenaries.[7]

The report could be a Russian information operation that would presumably intend to increase public support for an Africa Corps deployment or startle the West. Afrique Media has a media-sharing agreement with RT and has regularly spread pro-Russian and pro-Wagner information campaigns.[8] The article does not describe an imminent Africa Corps deployment as fact outside of its title and first sentence and instead relies on assessment language that describes the deployment as hypothetical. The article notes that “everything suggests” an Africa Corps deployment is imminent and that an Africa Corps deployment “would constitute” an important step for the Nigerien junta.[9] Such an information operation would presumably either aim to foment pro-Russian public sentiment to encourage the Nigerien junta to pursue an Africa Corps deployment or scare off Western countries like Italy and Germany that have continued to try and work with the Nigerien junta.[10]

Niger’s engagement with Russia in late 2023 and 2024 shares similarities with Burkina Faso’s engagement with Russia months before Africa Corps deployed to Burkina Faso, which occurred with little immediate warning. One hundred Africa Corps soldiers arrived in the Burkinabe capital on January 23.[11] The Russian deputy minister of defense met with Burkinabe officials in September and discussed defense cooperation but did not publicly disclose if Russian military personnel would deploy to Burkina Faso.[12] The only clear precursor to the Africa Corps deployment was the arrival of 20–50 Russian soldiers in early November 2023 that likely engaged in preliminary discussions and groundwork for the deployment.[13] Reputable France-based outlet Jeune Afrique reported at the time that an anonymous military source claimed the delegation was responsible for constructing barracks in a town near Burkina Faso capable of accommodating 100 soldiers, which is where the initial 100-strong Africa Corps contingent is currently stationed.[14]

Russian forces in Africa have been ineffective in counterinsurgency operations and would likely be more focused on advancing the Kremlin’s strategic aims rather than degrading insurgent support zones in western Niger. The Russian contingent of 1,000–2,000 troops in Mali has failed to degrade the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the country but is gaining increased access to valuable natural resources.[15] The Kremlin’s smaller deployment in Burkina Faso is primarily concerned with training and regime protection to boost the pro-Russian junta’s legitimacy and potentially secure access to valuable natural resources in the country.[16]

Niger’s strategic location at the crossroads of the Sahel creates even more opportunities for the Kremlin to advance aims, such as threatening Europe and consolidating its own position in Africa. Russia has systematically weaponized migrant crises in Europe and is looking to foment greater refugee flows to affect European elections in 2024, and Niger sits along a major and increasingly used trans-Saharan migration route to Europe.[17] A share in Niger’s large uranium deposits would increase its grip on the nuclear energy market to improve its leverage with countries seeking to cut Russian energy purchases.[18] CTP has previously noted that the Kremlin could use Niger-based drones to threaten critical areas along NATO’s southern flank, although this is unlikely in the near future, and Russian forces in Africa do not currently have their own drones.[19] Russian basing in Niger would also be centrally located and help close the logistics air gap between its positions in North and sub-Saharan Africa.[20]

Figure 1. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Clingendael Institute; Norwegian Center for Global Analyses.

Figure 2. Prospective Range of Iranian-Made Shahed 136 Drones from Agadez, Northern Niger

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian forces or drones in Niger.

Source: Liam Karr.

Figure 3. Russian Mercenary Facilities in Northwest Africa

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian forces or drones in Niger.

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

JNIM in Niger

Authors: Liam Karr and Matthew Gianitsos

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has increased the rate of its attacks in western Niger since the beginning of 2024, likely to establish new support zones that it can use to facilitate more regular and severe attacks on critical roads connecting Niamey and various district capitals. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) nearly doubled its number of attacks in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the fourth quarter of 2023.[21] The majority of these attacks occurred within 75 miles of the capital, including one attack in January that was one mile from the Niamey city limits.[22]

Two attack campaigns west of Niamey are driving the uptick in operational tempo. CTP has previously assessed that JNIM is likely seeking to establish new support zones with these campaigns.[23] JNIM has attacked the area between Samira and Gotheye at least six times since January 1.[24] These attacks mostly targeted civilians and civilian militias.[25] Security forces have relied on drone strikes to contest JNIM in the area and have been generally inactive in the area since February, indicating that JNIM has established a strong foothold in the area.[26] These types of operations signal that JNIM is aiming to remove Nigerien forces from the area and coerce civilians so it can ensure freedom of movement and access to resources.

JNIM has also carried out at least another six attacks near Ouro Gueladjo, which lies at the midpoint of a road connecting two district capitals, since January 1.[27] Security forces have maintained a presence in Ouro Gueladjo, but a continued high rate of JNIM improvised explosive device (IED) and ambush attacks around the town indicate that they have been unable to degrade JNIM’s capabilities in the area.[28] These kinds of attacks signal an effort to keep security forces out of surrounding rural havens so that JNIM can maintain freedom of movement and access to resources in these areas.

Figure 4. JNIM Escalates Attacks in Western Niger in 2024

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

JNIM likely already established a support zone southwest of Niamey toward the end of 2023 that it is using to support its current attack campaigns. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Database recorded at least nine instances of JNIM militants extorting “taxes” from villages in rural areas of the Torodi district in November 2023.[29] The group’s only activity in this area since was an IED attack in January 2024 targeting Nigerien security forces attempting to move through the area.[30] This area is situated between JNIM’s two major attack campaigns in Samira and Ouro Gueladjo, indicating that the group is using this haven to support those campaigns.

Additional support zones in southwest Niger would allow JNIM to expand the geographic scope of future attack campaigns, enabling it to amplify pressure on the roads surrounding Niamey during the coming year. JNIM’s attack campaigns near Samira and Ouro Gueladjo are near key roads leading to the capital. JNIM has already used its havens around Ouro Gueladjo and the Torodi district to attack the RN6 connecting Torodi town and Niamey. Militants can use the same havens they use to attack Ouro Gueladjo to facilitate attacks on the RN27, which connects Say and Niamey. Support zones in the Gotheye department would also enable attacks along the RN1 or RN4 highways that run along the Niger River and connect several department capitals in northwestern Niger to Niamey.

Degrading Nigerien lines of communication around the capital fits JNIM’s historical pattern of avoiding decisive battles for large population centers in favor of siege tactics that isolate security forces and spur favorable negotiations.[31] JNIM has been conducting such an attack campaign around the Malian capital since early 2023.[32]

Horn of Africa

Authors: Liam Karr and Josie Von Fischer

Ethiopia is advancing bilateral partnerships with de facto autonomous regions of northern Somalia, which is undermining the SFG’s legitimacy in these areas and exacerbating tensions between the SFG and Ethiopia. Ethiopia and the de facto independent breakaway region of Somaliland announced at the beginning of January that they had signed a deal that would grant Ethiopia land in Somaliland for a naval base in return for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[33] Ethiopia and officials from the de facto autonomous Puntland region have met multiple times in Ethiopia and Puntland in recent weeks to discuss security, economic, and political cooperation.[34] Ethiopian engagement with both regions legitimizes their existence as autonomous entities at the expense of the SFG’s de facto sovereignty over these regions.

Both regions’ cooperation with Ethiopia has inflamed preexisting tensions between the SFG and the regional governments. The SFG does not recognize Somaliland’s independence and has repeatedly rejected the port deal as a violation of its sovereignty since neither Ethiopia or Somaliland consulted the SFG about it.[35] The announcement scuttled potential dialogue between Somalia and Somaliland that aimed to ease tensions.[36] The recent flurry of diplomatic activity between Ethiopia and Puntland came days after Puntland announced it would function as an independent government until the SFG addresses its grievances surrounding the ongoing Somali constitutional revisions.[37]

The Somali government responded to the cooperation by expelling the Ethiopian ambassador from Mogadishu on April 4, recalling its ambassador, and ordering the closure of Ethiopian consulates in Puntland and Somalia.[38] Both Somaliland and Puntland have stated the SFG does not have the authority to close Ethiopian consulates in their respective regions, while Ethiopia has not publicly acknowledged the SFG’s decision.[39] SFG said it took these steps because of the Somaliland port deal.[40] However, the timing and rhetoric about Somalia’s internal affairs indicate that the moves were also in reaction to Ethiopia’s more recent engagement with Puntland.[41] The move risks further escalating the diplomatic crisis by placing Ethiopia in violation of international law, since the international community recognizes the SFG’s sovereignty over Puntland and Somaliland.

The overlapping domestic and regional crises with Ethiopia, Puntland, and Somaliland have weakened the SFG’s counterterrorism efforts. The SFG has given priority to these issues over its counterinsurgency campaign against al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab, undermining the fight against the group and contributing to its retaking territory in central Somalia.[42] The fallout surrounding the Ethiopia-Somaliland port deal has also weakened counterterrorism cooperation with Ethiopia and the UAE, which have been critical partners in recent years. CTP assessed that Somalia’s agreement with Turkey alienated the UAE, which is close to Ethiopia and competing with Turkey for influence in the region, contributing to the UAE decreasing financial and training support for Somali forces.[43] The diplomatic standoff between Ethiopia and the SFG also jeopardizes military cooperation with Ethiopian forces fighting al Shabaab in Somalia, which the SFG had hoped to use as part of a counterinsurgency offensive in southern Somalia.[44]

Somalia

Author: Liam Karr

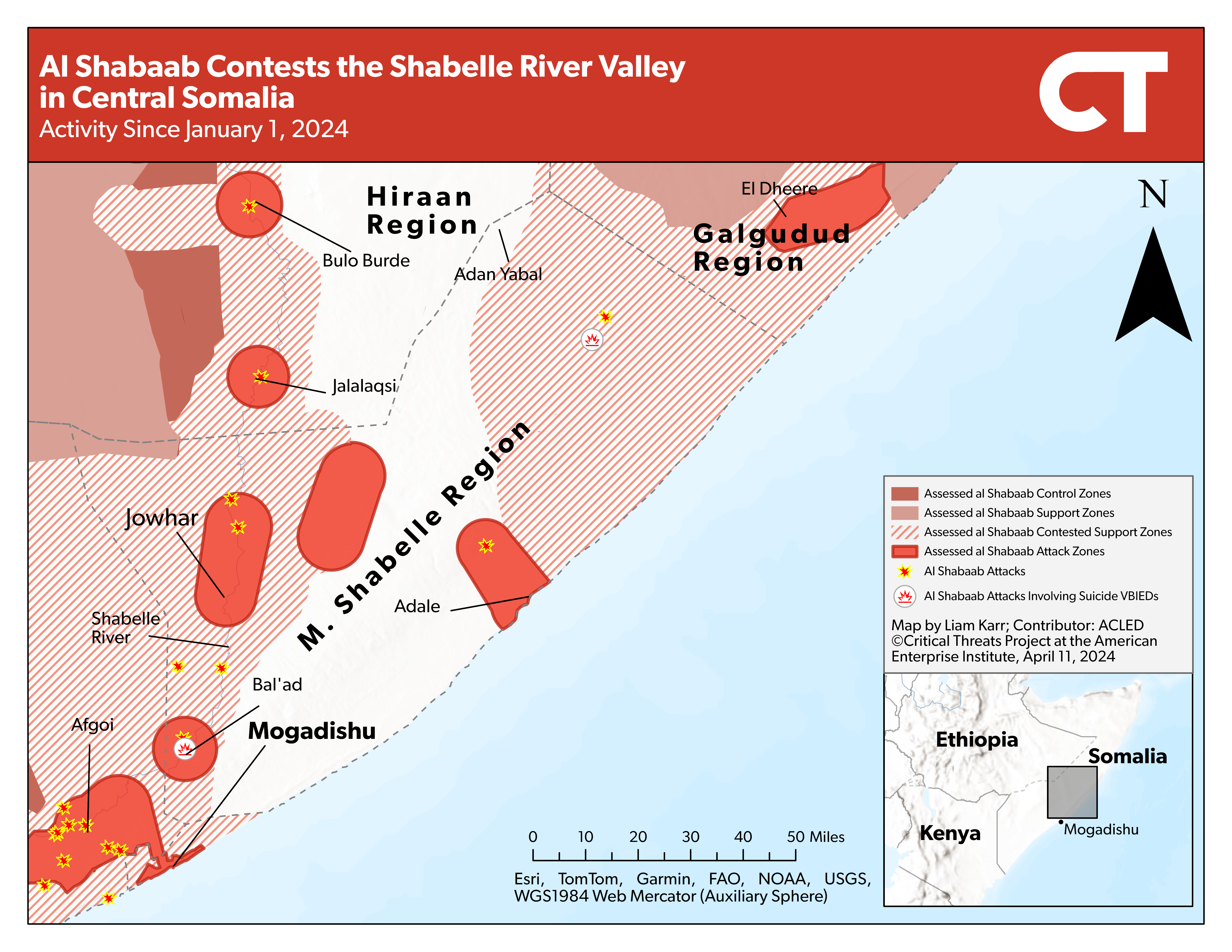

Al Shabaab launched a complex attack targeting a district capital in south-central Somalia, underscoring al Shabaab’s ongoing resurgence in areas that Somali forces liberated during the 2022 central Somalia clan uprising and counterterrorism offensive. Al Shabaab launched a three-pronged complex attack involving a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (SVBIED) targeting three security checkpoints and the regional intelligence headquarters in Bal’ad on April 6.[45] Bal’ad is a district capital 25 miles north of Mogadishu in the Middle Shabelle region. Somali officials claimed that security forces repelled the attack and killed 11 militants at the cost of at least four Somali soldiers.[46] The attack is the second involving a SVBIED in central Somalia and the fourth across the country since the beginning of Ramadan on March 10.[47]

Figure 5. Al Shabaab Contests the Shabelle River Valley in Central Somalia

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

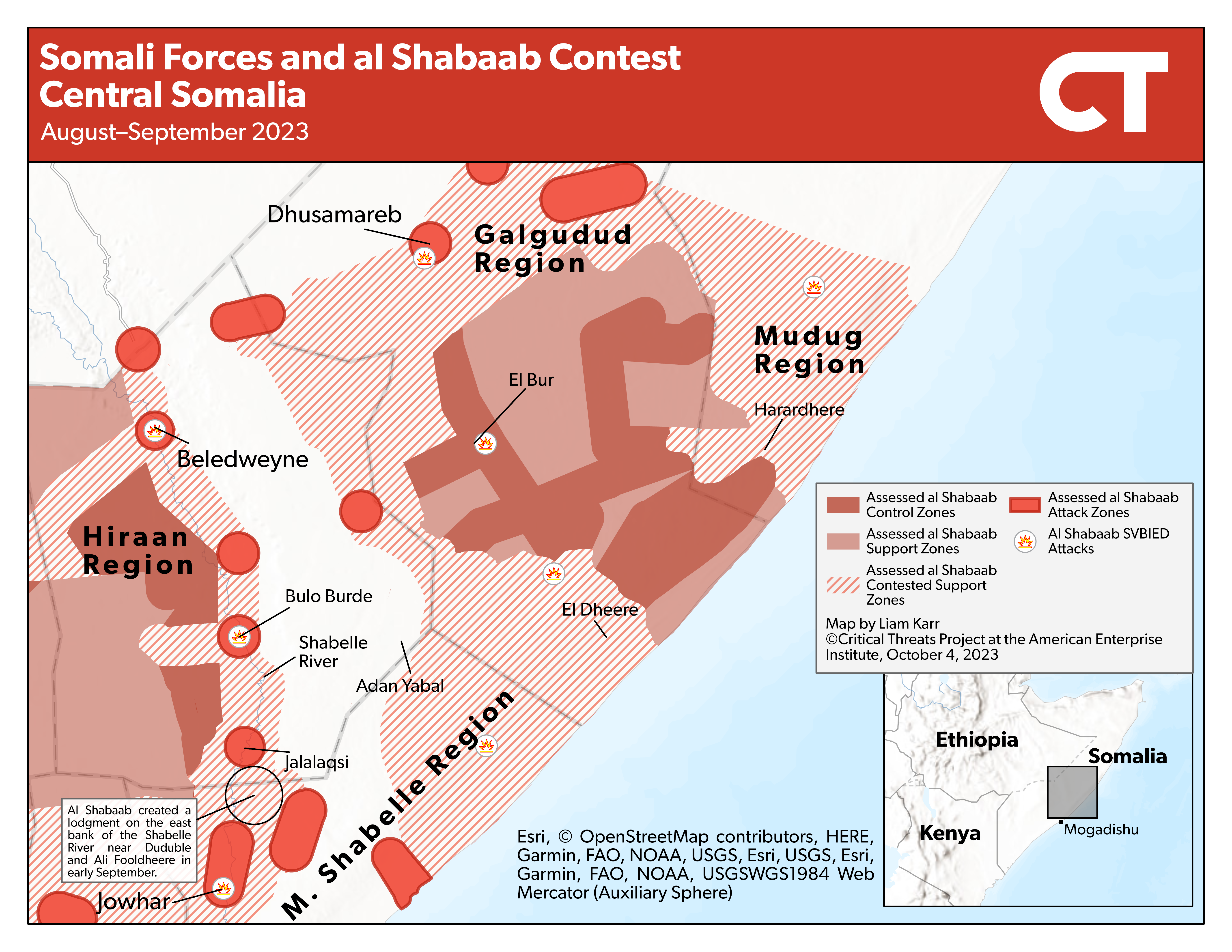

Al Shabaab had not conducted an attack of this scale in the western half of the Middle Shabelle district since September 2023, when it launched an offensive to reestablish itself in the area. The group conducted an offensive in the neighboring Jowhar district in August and September that involved a separate SVBIED attack on Jowhar town.[48] The group also launched an unsuccessful large-scale operation to establish a lodgment on the east bank of the Shabelle River.[49] The offensive and operation were 30 and 50 miles north of Bal’ad, respectively.

Al Shabaab had not conducted an attack this sophisticated in the Bal’ad district specifically since Somali forces cleared al Shabaab from most of the Middle Shabelle region in the fourth quarter of 2022.[50] Somali forces and local clan militia cleared al Shabaab from the Bal’ad district in October 2022 and liberated the last al Shabaab–controlled town in the wider Middle Shabelle region—nearly 125 miles northeast of Bal’ad—on December 22.[51]

Figure 6. Somali Forces and al Shabaab Contest Central Somalia: August–September 2023

Source: Liam Karr.

Al Shabaab threatens to reestablish a foothold in the Middle Shabelle region through its control of the west bank of the Shabelle River. CTP assessed in October 2023 that al Shabaab would be able to use these havens to continue manufacturing VBIEDs and staging fighters for attacks like the April 6 attack on Bal’ad.[52] Several unconfirmed claims on Twitter say that the group sent a separate group of fighters across the Shabelle River in early April 2024 to reestablish a foothold in various rural areas of Middle Shabelle, repeating the tactics of its failed offensive in September 2023.[53] Al Shabaab has used a combination of SVBIED and large-scale infantry assaults to successfully retake areas of north-central Somalia, where the group’s havens, supply chains, and local bomb-making facilities have remained similarly intact.[54] Somali forces will eventually have to clear these remaining areas to safeguard their successes from 2022.