Angola

From Nairobi, it’s time to travel back to the west coast as we land in Luanda, Angola. After years of economic mismanagement and neglect under the Dos Santos family, the country became financially distressed long before Covid emerged.

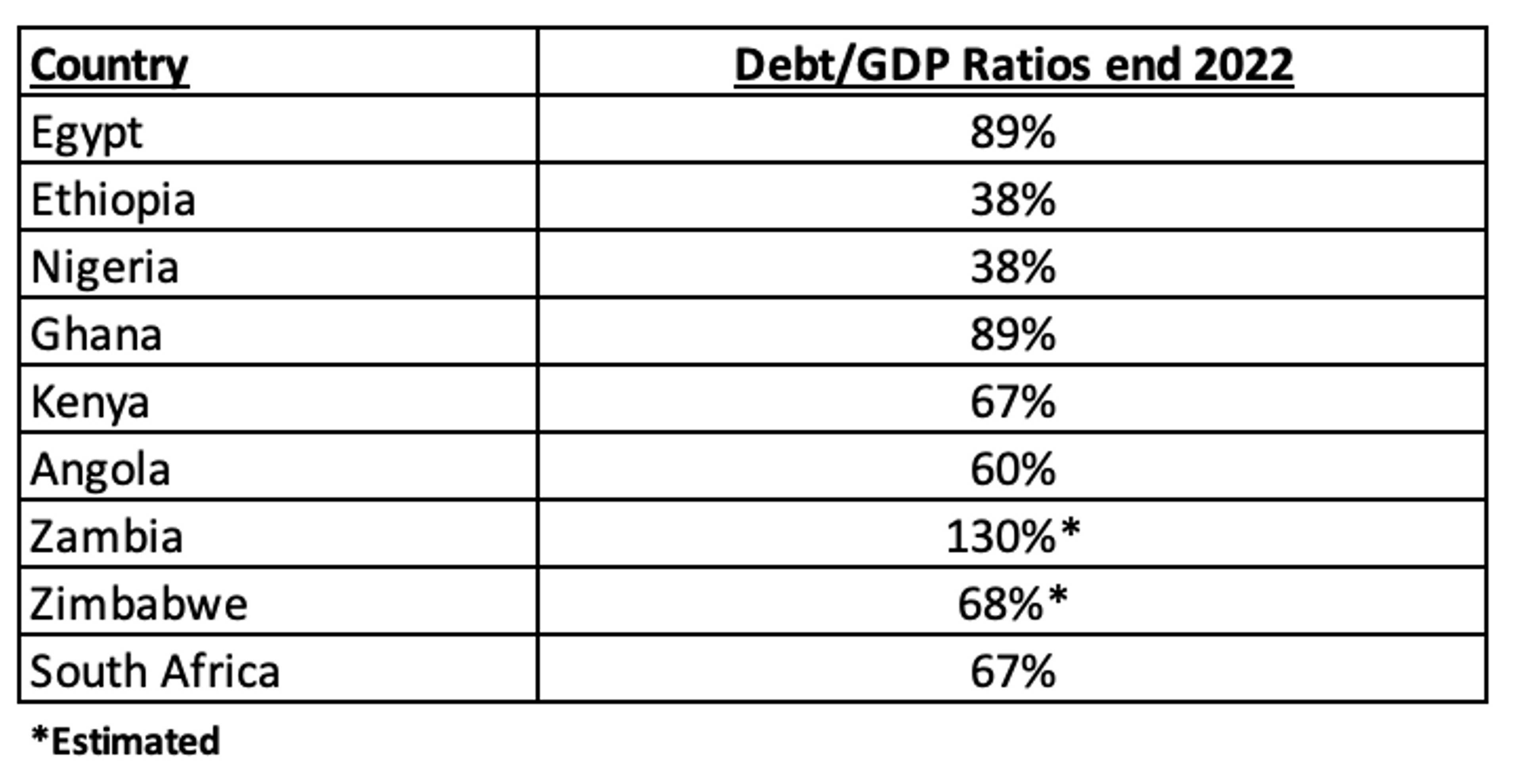

In December 2018, Angola struck a deal with the IMF to borrow $3.7bn over three years.Two years later, government debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 120%.

Angolan president Joao Lourenco (who succeeded Jose Eduardo Dos Santos in 2017) committed to an ambitious reform programme, promising to privatise 195 state assets. But many of these companies are unfit for sale and will probably have to be closed.

Lourenco moved swiftly to prosecute the Dos Santos family for corruption and recover funds believed to have been embezzled by the family. This has included targeting Isabel dos Santos, who is facing legal challenges in three countries and who has been effectively exiled in the United Arab Emirates.

With better management of its finances, the country (which is a large oil exporter) used the revenues from higher oil prices in 2022 to reduce its debt-to-GDP to 60%. This prompted an upgrade in its credit rating and allowed the country to issue a $1.75bn Eurobond last year. Angola will use some of the proceeds to repay debt that was deferred during the pandemic, and its interest costs are expected to amount to 23% of government revenues this year.

Zambia

From Angola, we head to Zambia where the country under president Hakainde Hichilema is dealing with its $28bn debt headache, most of which ($21bn) is external.

But in doing so, Zambia has found itself in the middle of a tug-of-war between superpowers competing for influence. Besides a range of western based creditors, Zambia owes money to a variety of Chinese lenders which include the Chinese government and state-owned entities. The Export Import Bank of China, for instance, is owed $4.1bn.

While creditors were being asked to take “haircuts” – financial slang for sharp write downs on the amounts they are owed, it appears China was unhappy that the IMF and World Bank were not being asked to share the pain.

There was also a feeling that China - as the largest lender to the developing world - was unhappy being dictated to, which it felt prevented it from solving Zambia’s repayment problem in other ways.

After months of negotiations, Zambia clinched a deal in June with official creditors. It appears to have secured very generous terms. By one account, it will only have to repay $750m in the next decade (as opposed to the original $6.3bn). For the first three years, Zambia is obligated to pay interest amounting to just $75m a year.

The deal also means Zambia can resume borrowing from other Multilateral Financial Institutions (MFIs). The country intends to negotiate with private creditors (who are owed $6.8bn) to try and secure further concessions that will ease its path back to financial sustainability.

With all these strained African government balance sheets, it's time to continue south. As we climb out of Kenneth Kaunda International Airport, we are confronted by the enormous mass of water encompassing Lake Kariba.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s financial predicament has been apparent for sometime. Defaulting on its obligations in the 00’s and failing to clear its arrears has disqualified the country from borrowing from MFIs which include the African Development Bank (AfDB).

Under the regime of Emerson Mnangagwa, Zimbabwe committed to a mediation process led by AfDB President, Akinwumi Adesina, and former Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano. The purpose of these engagements - referred to as “Structured Dialogues” - between the government and a team of technical experts, is to find consensus on a broad range of economic, monetary and political reforms that Zimbabwe must undertake to clear its name and normalise its relationship with the international community.

One of the key requirements is that Zimbabwe holds free and fair elections next month. But controversy over publication of the voter’s registration roll and the signing into law of a number of draconian bills, may well cast a long shadow over its chances. The threat of political violence and intimidation in the build-up to the elections looks very real.

South Africa

As we enter South African airspace, it is worth noting that while the country is not in a crisis with government debt to GDP sitting at 67%, it is not yet out of the woods. South Africa has a massive advantage over many of its peers in that it sources most of its borrowing in Rands and is largely immune from wild swings in debt repayments that come with foreign debt.

But the economy has barely grown in the last five years, as the government persists in trying to control strategic sectors of the economy through state-owned enterprises in which it appoints executives based on political allegiance and not competence. This has led to much of the rot at state-owned entities like Eskom.

And despite talk of a clean up after the dark years of State Capture, corruption and lawlessness under President Ramaphosa is arguably worse than it was under his predecessor, Jacob Zuma. Sadly, the section of the population that appears to have borne the brunt of the economic incompetence are the youth - with nearly one out of two people under the age of 30 unemployed as of March this year.

Where next?

So as we take in the magnificent sight of Table Mountain in Cape Town, we begin to appreciate the magnitude of the problem affecting citizens in all corners of the continent. Countries are at different stages of managing the crisis. There could yet be more angry public protests as governments confront hard choices about where they spend their next Naira, Shilling or Kwacha. The crisis might well see governments facing imminent elections, being voted out in favour of parties that promise less austerity.

But there also needs to be a review of foreign borrowing and the role this type of lending has played in the sovereign debt crisis. When should governments borrow in foreign currencies? What projects should be financed? What is a responsible limit? How can the process become more transparent? What changes need to be made to legislative and governance institutions in each country to enable better debt management? The answers to these questions should form the basis of preventing this crisis from happening again in the future.

For every problem there is a solution, and that is what we hope to be addressing in the coming weeks.