High-profile political violence in Ethiopia has brought into question Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s ability to implement long-awaited political reforms. Abiy inherited a divided country, and his primary tasks are to reduce violence, encourage a more participatory political system and establish free elections. Importantly, he needs to create a more unified federation – Ethiopia has rarely been able to maintain civil order in such a politically decentralized system. So for Abiy, the challenge is twofold. He needs to figure out how to govern a multinational state, and he needs to define a government that has struggled to define itself ever since the end of the Cold War.

A Rise of Militias

But reforms tend to upset one side or another, and in Ethiopia’s case, they have stoked ethnic tensions that have led to political violence. On June 22, the governor of Amhara state met with his chief of staff to discuss the rise of nationalist militias. Both of them were fatally shot in what the central government called an attempted coup. Shortly thereafter, the chief of staff of the Ethiopian army, an ethnic Tigray, was shot and killed by his bodyguard, who just so happened to be ethnically Amhara.

The federal government in Addis Ababa blamed the attacks on Gen. Asaminew Tsige, a well-known Amhara nationalist who had recently called for the growth of Amhara militias. It was particularly problematic given his position as the head of Amhara’s Peace and Security Bureau – a post to which he was appointed to appease Amhara nationalists who were upset at the federal government and the Amhara Democratic Party’s role in it. (The ADP is a partner of the ruling coalition.) The plan to cater to the nationalists clearly backfired.

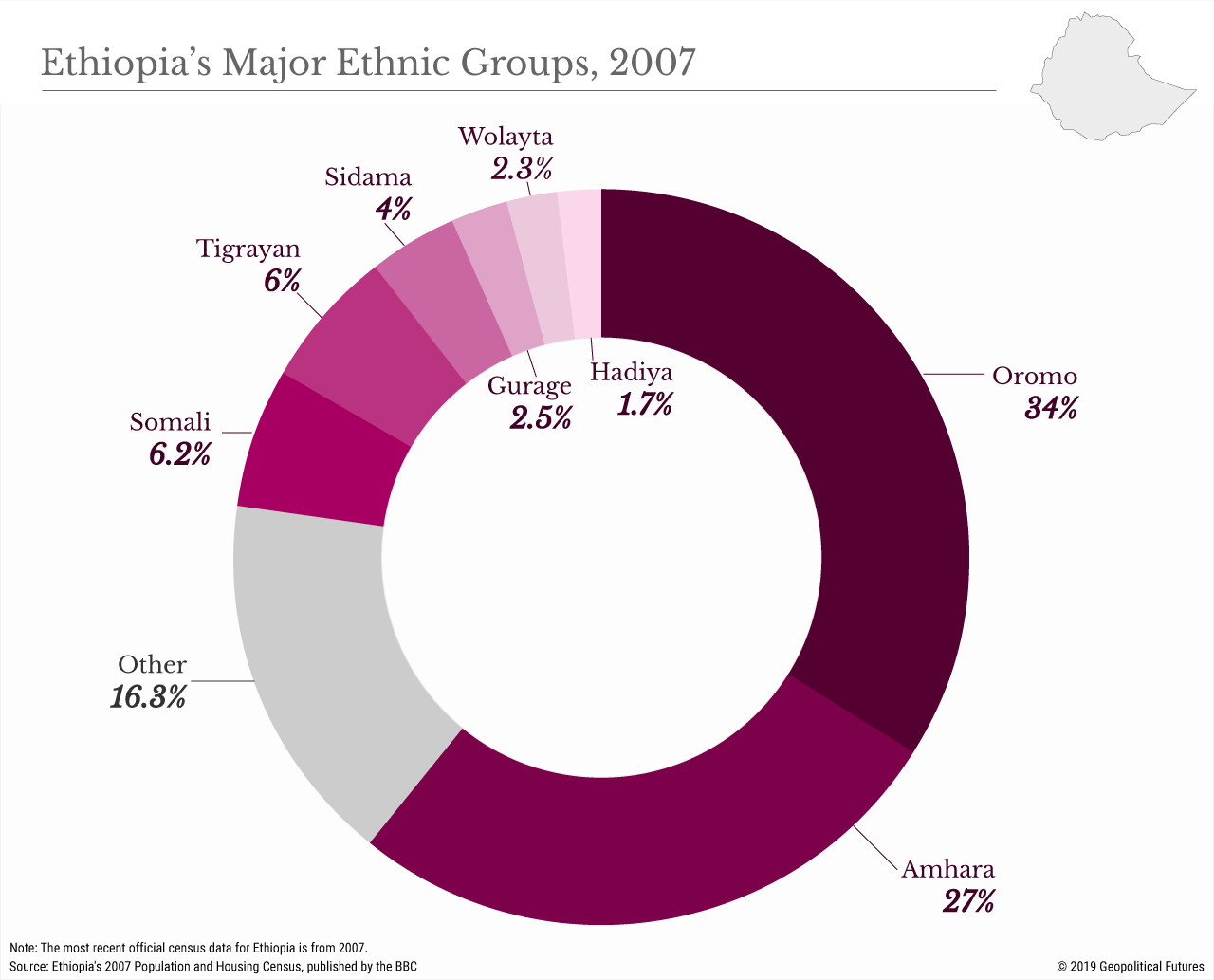

The symbolism of the assassinations wasn’t lost on the government – or the Ethiopian people. Ethnic nationalism has long been a countrywide issue. Social unrest associated with it was, after all, the impetus behind former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn’s resignation and replacement by Abiy. The public generally welcomed the changing of the guard, but Abiy’s promises for reform were quickly halted by political reality. Ethiopia is a diverse country with a lot of competing interests, and it’s difficult to satisfy all those interests even with adequate resources – which Ethiopia lacks.

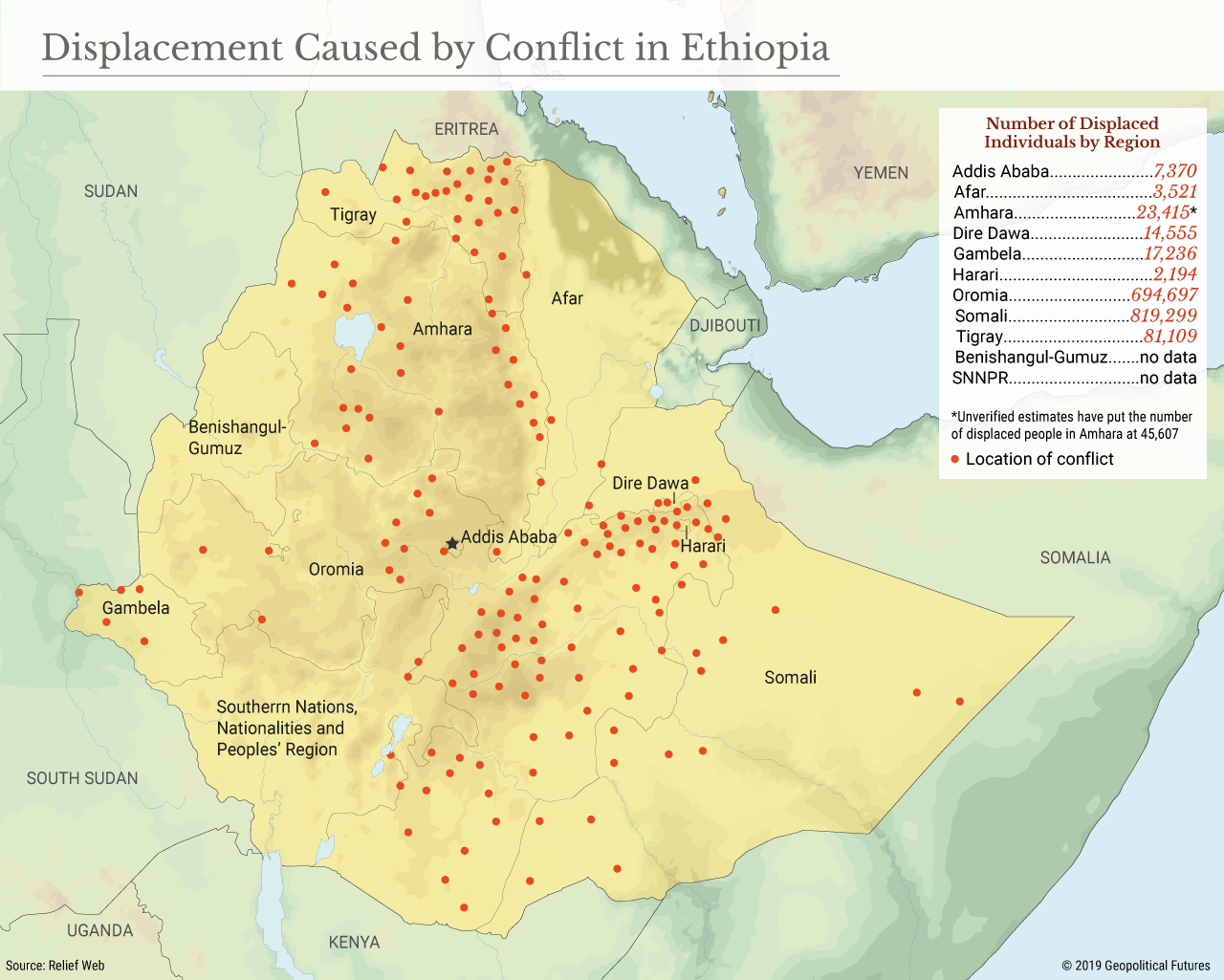

As a result, ethnic militias are mobilizing throughou t the country to protect and even advance their interests. The Somalis have the Somali Special Force; the Oromo have the armed wing of the Oromo Liberation Front. Fighting between the militias of the ethnic Gujis and Gedeos in the Guji zone of Oromia has displaced countless citizens. Amhara and Tigrayan forces routinely clash at contested points along their border. In Harar, some ethnic Hararis have been forcibly removed from their homes by Oromo, and a string of retaliatory clashes have recently been reported in the region of Benishangul-Gumuz.

t the country to protect and even advance their interests. The Somalis have the Somali Special Force; the Oromo have the armed wing of the Oromo Liberation Front. Fighting between the militias of the ethnic Gujis and Gedeos in the Guji zone of Oromia has displaced countless citizens. Amhara and Tigrayan forces routinely clash at contested points along their border. In Harar, some ethnic Hararis have been forcibly removed from their homes by Oromo, and a string of retaliatory clashes have recently been reported in the region of Benishangul-Gumuz.

The size of any given militia group varies. Oromo militias, which are among the largest, can number a few thousand and have training camps large enough to invite military airstrikes (which happened last February). Others number in the hundreds or even less. And some militias are certainly more capable than others. The Amhara, for example, carried out coordinated assassinations in separate cities. More sophisticated groups will also have more access to better firearms than others.

The formation of the militias, moreover, comes at an inopportune time for the government, which is restructuring and reforming its own security forces. The reforms are intended to make the armed forces more representative of the country’s population. But Abiy is also purging the military of his potential enemies and consolidating control. His anti-corruption campaign targeted the old guard of his predecessor and included the removal of at least 160 generals and dozens more leading officers from military intelligence. He is meanwhile trying to gain entree with the rank and file, pacifying, for example, several hundred protesting soldiers last year by paying them more. All told, it’s a disruptive process that has naturally created tension within the military as reforms play out. After the recent assassinations, Abiy reiterated his authority as commander in chief, praised the military for its work and reminded them of the need for a unified federation. And though he controls the Defense Council and much of the military intelligence, there are still pockets of discontent. The bottom line: With so much uncertainty in the military, and with an ethnic militia in nearly every corner of the country, it’s a bad time to stretch soldiers so thin.

The presence of these militias obviously raises questions of independence or secession. At least 10 ethnic groups in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region, Ethiopia’s most ethnically diverse and heterogeneous region, for example, have filed petitions to create their own state within the federation of Ethiopia. (The Ethiopian constitution grants ethnic groups the right to petition for the creation of their own state.) Sidama zone may soon hold a referendum on statehood. Others, however, are going a step further by calling for outright secession. The most recent call has come from the Tigray, who have accused the federal government of ethnic violence against them. Their accusations are not without merit. The Tigray disproportionately dominated the political system that Abiy took over, so Abiy’s purges have disproportionately targeted them. Technically, the constitution also allows for legal secession, but it’s never been tried, and the belief that a nation that did secede would have the arduous tasking of trying to survive on its own tends to discourage calls for secession. More likely, disgruntled regions will cause some trouble and make some noise, which creates the kinds of problems present in Ethiopia today.

Three Attempts

These problems take place just as Ethiopia tries to function, for the third time ever, as a united federation without an authoritarian central government. Modern Ethiopia’s first attempt at federalism occurred under Emperor Yohannes (1872-1889). As he expanded his domain, rulers of newly acquired territories were given a high degree of autonomy, so long as they still answered to the emperor. (His successors ultimately opted for more centralized control.) The second attempt of was made by the Derg military government (1974-1991). The Derg was only nominally federal, however, and it cracked down violently on nationalist regional movements.

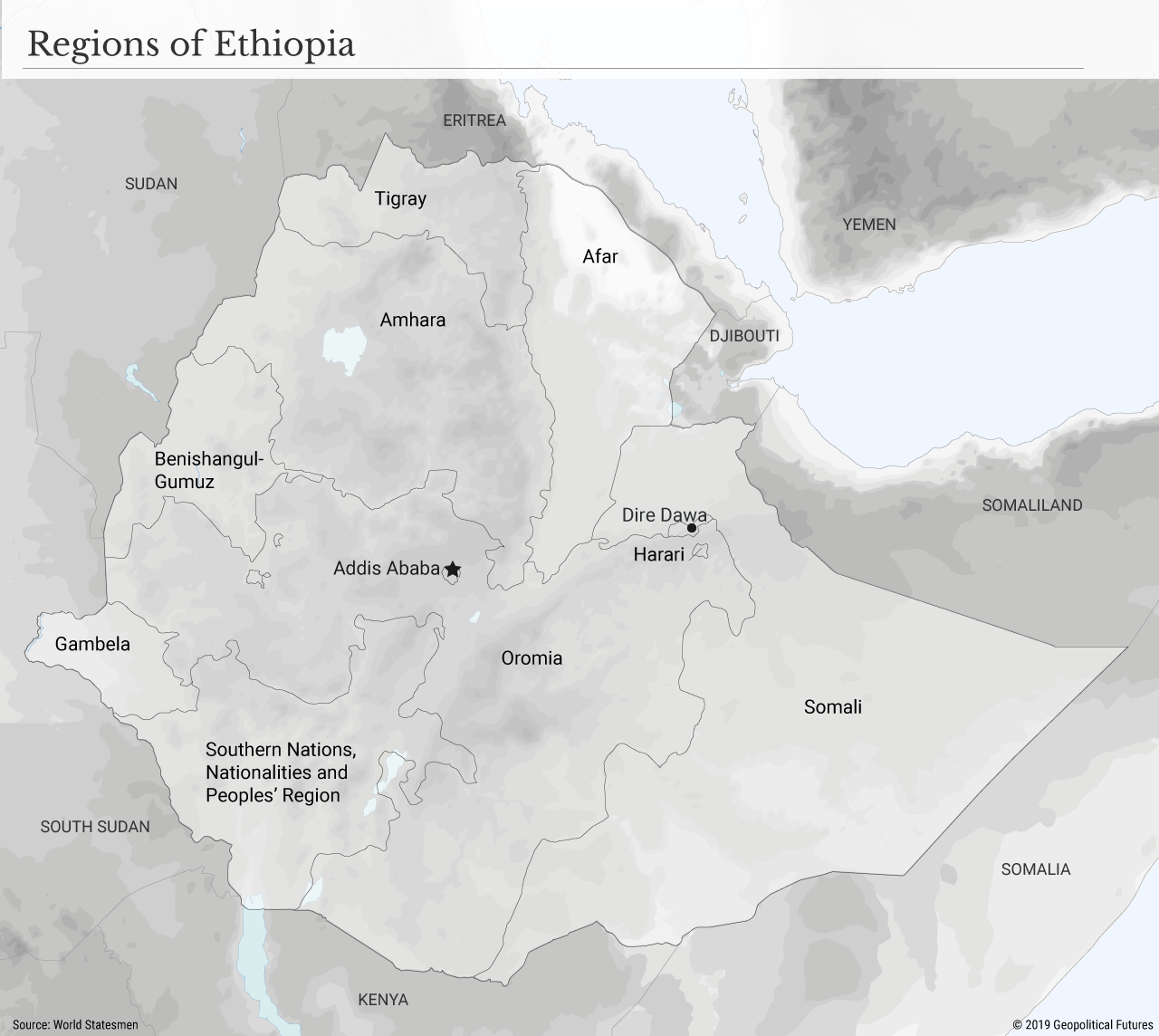

The third and current attempt is a product of the 1994 Constitution, which has proved to be a well-intended but flawed document. The authors understood that the country’s ethnic diversity needed to factor into the state’s political organization, but the administrative regions as constituted aren’t completely homogeneous either. The ethnic group that is considered indigenous to each region has rights to land, government jobs, and representation in local and federal bodies that minorities do not. The federal system, in other words, is demarcated along ethnic, not geographic, lines.

The 1994 Constitution, moreover, still indirectly encourages centralized power. The document was heavily influenced by Marxism, Leninism, revolutionary democracy, democratic centralism and so on. So the ruling party tends to dominate the system despite the higher degrees of autonomy afforded to the regional governments. It also creates an extensive patronage system that induces fealty to the ruling party. It’s a top-down style of governance that leaves little wiggle room for regional authorities.

You can start to understand why ethnic violence is endemic in a country like Ethiopia, and why the violence casts doubt on Abiy’s ability to honor his promises of reform. The recent assassination attempts may just be the beginning of more unrest to come. Some groups have broached the possibility of constitutional reform, with the All Ethiopian Unity Party calling for the removal of Article 39 on the grounds it poses a threat to Ethiopian unity. The national census may be delayed for a fourth time because of security concerns, and if those concerns are not addressed, they could interfere with the long-awaited elections of 2020. It’s not implausible, then, to think Abiy could centralize even more power for the sake of security.

When Abiy introduced the idea of reform, he opened the floodgates to demands that have been suppressed for decades. It’s unclear if Abiy can manage them. But it is clear what kind of constraints he has to overcome to manage them. The move requires transcending structural issues that plague the country and will inevitably include violence along the way.