Date: Thursday, 20 September 2018

By Sydney Deatherage

September 19, 2018

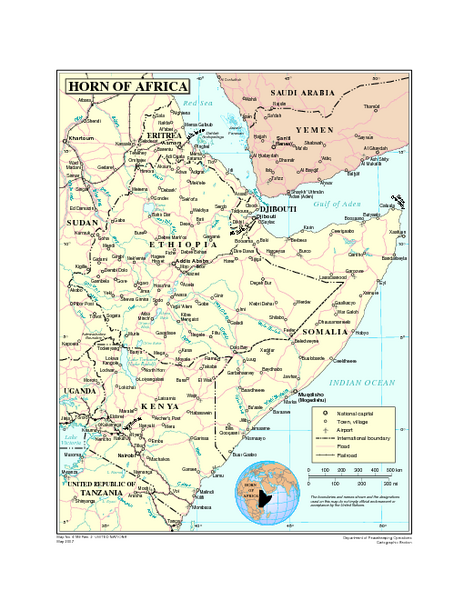

Since June 2018, a wave of political change has swept through the Horn of Africa, where long-entrenched hostilities have contributed to insecurity and economic stagnation. The latest of these events took place on September 6, 2018, when the presidents of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia held high-level meetings in Djibouti, and Eritrea and Djibouti agreed to normalize relations. This event was preceded by Ethiopia’s restoration of ties with Somalia on June 16, Eritrea and Ethiopia’s formal end to their 20-year war on July 9, and Somalia and Eritrea’s normalization of ties on July 30. Hopes are high in the Horn, but what are the stakes?

The Players

Ethiopia: Ethiopia is the economic and military powerhouse in the Horn, but it has struggled with ethnically based political turmoil. The Tigray minority—hailing from the region bordering Eritrea—has dominated Ethiopia’s government and military for decades through the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). After years of political repression, escalating protest from the Oromia region and a new

alliance between Oromo and Amhara activists have put pressure on the TPLF. As a result, the Ethiopian government replaced unpopular Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn with Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, in May.

Countries of the Horn of Africa. (Source: United Nations,

Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Cartographic

Section, Map No. 4188, Rev. 5. March 2012.

http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/map/profile/horne.pdf.)

Eritrea: Under the 25-year regime of President Isaias Afwerki, Eritrea remains one of the most isolated and undemocratic countries in the world, with compulsory long-term military conscription, a suffering command economy, and one of the world’s worst human rights records. Eritrea has been subject to international sanctions since 2009 for its support of al-Shabaab militants in Somalia and aggression against Djibouti. It has justified its perpetually militarized state on the basis of its border conflicts with Ethiopia and Djibouti, as well as general hostility toward Somalia. Eritrea has never held elections, and ailing 72-year-old President Afwerki has not named a successor.

Somalia: Somalia remains the most unstable regional state. Its government has made uneven progress against the al-Shabaab insurgency, lacks control over large swaths of territory, and is plagued with clan violence and corruption. President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmaajo, who came to power in 2017, has had some success in sustaining popularity across clans and garnering donor support.

Djibouti: Djibouti, which has been under the regime of President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh since 1999, is the most politically stable in the region. Its strategic location at the intersection of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden is the basis of its economy, and it hosts the most diverse array of foreign military bases in the world, including those for the United States, France, Great Britain, Japan, China, and Saudi Arabia. Djiboutian ports have been one of few points of sea access for Ethiopian exports.

The Stakes

Interstate tensions in the Horn are deeply rooted and enduring. Ethiopia and Eritrea have existed for 20 years in a state of “no war, no peace.”Tensions have troubled relations between Ethiopia and Somalia. Eritrea and Somalia have not had diplomatic ties for 15 years due to Eritrea’s support of al-Shabaab in Somalia, while Eritrea and Djibouti have shared hostilities over a border dispute.

What do these countries stand to gain from recent diplomatic maneuverings? First, for Ethiopia and Eritrea, the restoration of diplomatic ties supports the narrative of reform its leaders are utilizing to quell domestic discontent. In Ethiopia, this change in government is the latest of a series of rapid reforms. The restoration of trade and economic ties with Eritrea is an important step for a country that has indicated its intent to open its private sector. In Eritrea, formalizing the end to conflict with Ethiopia may help Afwerki fulfill his promise to reform military conscription. Second, in addition to pursuing reform, Ahmed and Afwerki also have a common enemy in the TPLF, the previously dominant Ethiopian political party that continues to hold significant official and unofficial power. The TPLF-dominated Ethiopian military has yet to withdraw from the Eritrean border, although on September 11 both countries announced plans to withdraw troops. Third, for landlocked Ethiopia, access to Eritrea’s ports might diminish the costs of trade. Finally, in restoring ties with Eritrea, both Ethiopia and Somalia issued calls to end international sanctions on Eritrea. These overtures may diminish Eritrea’s image as a pariah.

For a fragile Somalia, engaging in regional diplomacy helps it project an image of improved central authority and institutional capacity. Implementation of the economic agreements resulting from this diplomacy—such as its agreement with Ethiopia to open four seaports —would make regional actors greater stakeholders in its security and development. As international debates continue over reducing the African Union Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), Somalia has a strong motive to engage its immediate neighbors.

Finally, Djibouti in its call for the UN to mediate its border dispute with Eritrea in July may have seen an opportune moment to extract concessions from Eritrea, given that country’s efforts at conciliation in the Horn. Indeed, in a win for Djibouti, Eritrea’s commitment to normalize ties last week may partly reflect pressure to maintain its new conciliatory image.

The Risks

In gauging the potential for a positive outcome from these diplomatic events, Eritrea is the wild card. Rarely has the liberalization of undemocratic and low-income societies been a peaceful process. With newfound freedoms and economic privatization, citizens typically demand more accountability from their governments, and this often results in unrest. As the primary justification for its mass forced conscription fades and the practice is limited, Eritrea’s rulers will be faced with a militarily oriented and largely unemployed population. With an aging and recently sick leader with no plan for succession, the possibility of volatility is increased.

A similar risk exists in Ethiopia, with a large proportion of its military deployed on the Eritrean border. Furthermore, this military is dominated by the TPLF, which may not be pleased with rapprochement with their historic enemy.

In Djibouti, Ethiopia’s moves to open ports in Somalia and Eritrea pose a threat to its monopoly on Ethiopian export routes.

There is less risk in Somalia to regional rapprochement because it only stands to gain from increased economic engagement with its neighbors. Whether Somalia’s domestic security situation can improve enough to absorb economic investment that normalization of ties promises is another question.

Conclusion

The diplomacy taking place in the Horn is progress in its own right. Without apparent pressures from international actors, over the course of four months leaders in the Horn issued well-received public overtures; held bilateral, tripartite, and regional high-level meetings; opened embassies; and signed political and economic agreements—many of which they are already implementing. The progress made, however, is fragile and could easily be shaken by domestic events. Should Ethiopia’s fragile course of reform hold steady, it may be what transpires in Eritrea—the wild card and the pariah—that determines the outcome of rapprochement.