The Cabinet has a golden opportunity to build political consensus and address citizens’ concerns.

The announcement on February 8 of a new Cabinet in Khartoum—the product of a peace accord signed by Sudan’s transitional government with several armed groups in October 2020 through a deal brokered by South Sudan—offers hope that the broader inclusion of political leaders can help address Sudan’s pressing challenges and create peace dividends. Unfortunately, the lengthy process of selecting new Cabinet members revealed additional fractures among both signatories to the peace deal and civilian political elements that seemingly offer competing visions for the transition and beyond.

Twenty-five ministers were announced. All but five ministers were replaced. Only four of the ministers are women. The ministers of defense and interior hail from the security sector as previously agreed between the government’s civilian and military factions. Some posts have gone to high-profile political leaders—for example, Gibril Ibrahim from Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement has been appointed finance minister and Mariam Sadiq al-Mahdi from the Umma Party is the new foreign minister.

In addition to representatives of groups from Sudan’s peripheries, such as Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile, the east and other areas, the refashioned Cabinet introduces new leaders from the broad yet fragile Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance. The FFC brought together political and civic groups around the 2019 revolution that led to the ouster of former dictator Omar al-Bashir and reached a deal with Sudan’s military to govern the transition. FFC’s members run the political spectrum from leftist politicians and civic and labor leaders to conservative sectarian parties. While this diversity is impressive, it has sometimes resulted in difficulties forming decision-making mechanisms and reaching consensus among alliance members. This is partly responsible for the FFC’s struggle with articulating a unified vision for the transition.

Building Confidence in Peace and Power-Sharing

For those ministers representing armed movements, it will be important to build trust with citizens that may view them as closer to Sudan’s security elements than the nonviolent street revolutionaries who ended Bashir’s nearly 30-year grip on power. A way to achieve this is for the Cabinet to begin implementing the complex October 2020 peace deal and ensure that the public understands the agreement’s national impact. Simultaneously implementing the agreement, running a government and continuing to reform the ministries that new ministers will oversee is a tall order. However, effective coordination across ministries—perhaps via a more proactive Ministry of Cabinet Affairs—and transparent decision-making can help.

Many Sudanese, understandably, remember prior peace deals centered around elite power-sharing with cynicism; once in Cabinet positions, many officials focused more on horse-trading and wealth accumulation than governance. Responsible governing by the new Cabinet may increase public confidence in leaders from the armed groups and could create a more stable environment for elections planned for the transition’s end.

Urgent Decisions or Paralysis?

Having reached consensus on political representation, the new Cabinet will need to quickly show that its broad coalition of forces can work closely with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok to address key issues. It is also important for the Cabinet to have the strong backing of Hamdok and key officials in his office to take unpopular decisions when needed. Some key issues are: unifying exchange rates and continuing to reform subsidies; engaging with military leaders to begin security sector reform that prioritizes citizens’ security; reenergizing negotiations for a more comprehensive peace that includes important armed movements from South Kordofan and Darfur; navigating legitimate demands for transitional justice and accountability; and outlining a foreign policy that defuses regional tensions—especially with Ethiopia and also due to the ongoing Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam negotiations—and reappraises Sudan’s relationship with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and other Gulf states.

The Cabinet can do much to address these issues on its own, but it will also need to work on them with the transitional government’s Sovereign Council, the mixed military and civilian body currently led by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan that acts as Sudan’s head of state. In a February 4 decree, three peace accord leaders from Darfur and Blue Nile were added to the council in a move related to the formation of the new Cabinet.

Ministers should also push for the creation of outstanding government commissions, as well as institutions like the long-delayed Transitional Legislative Council. Strong engagement between the Cabinet and this body can improve avenues for government oversight and public trust in both institutions.

During Bashir’s National Congress Party era, political and armed actors appointed to Cabinets were often viewed as collaborators with neither independence nor authority. Now, the opposite appears true; current ministers represent several sources of power and some can mobilize constituencies in support of, or against, decisions. It will be imperative for such ministers to indicate that they collectively represent the diverse landscape of Sudanese political, geographic, and social groups. More importantly, they must show through action, not just rhetoric, that such diversity can be harnessed to address the root causes of Sudan’s conflicts.

An Historic Time in Sudan

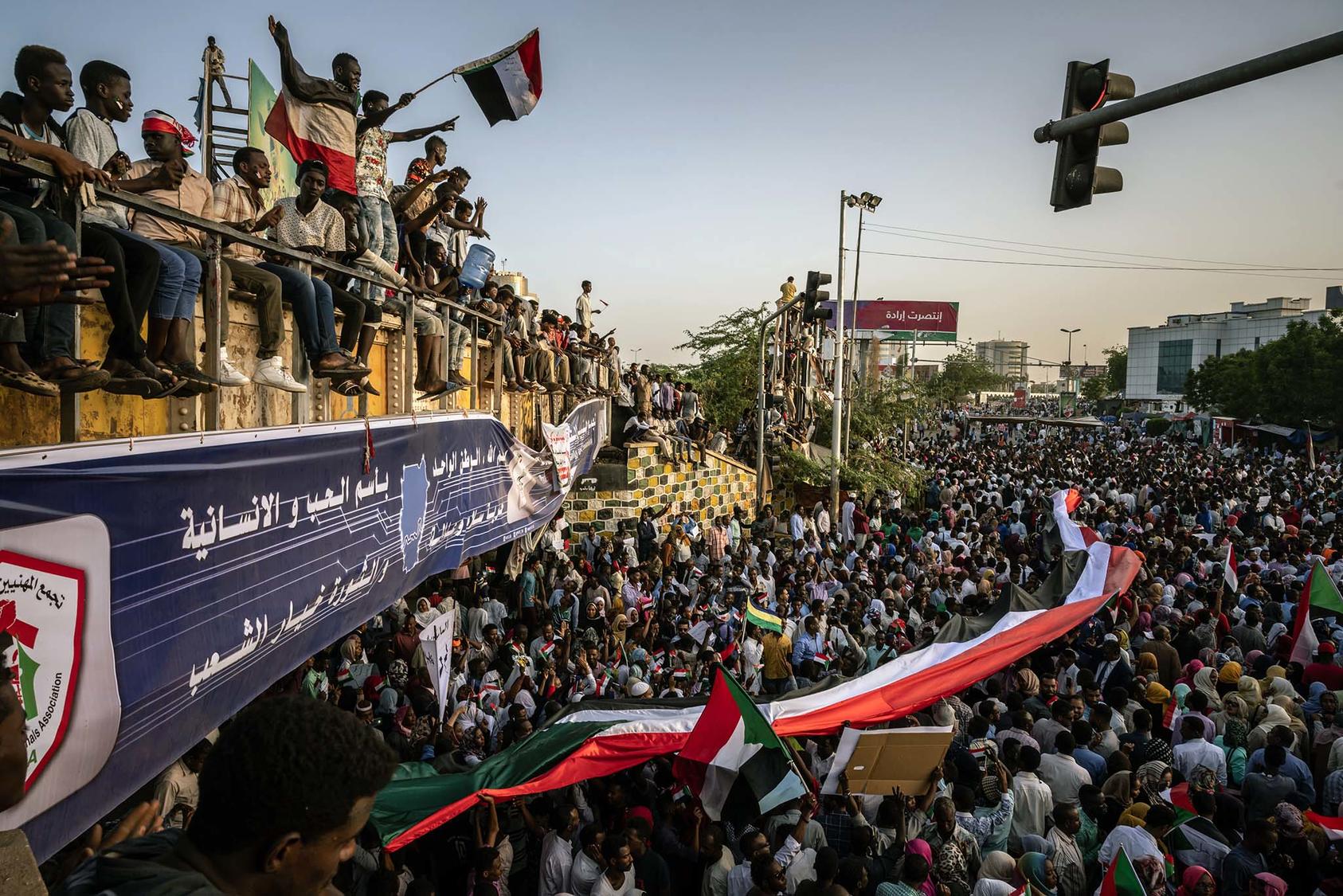

Sudan is going through a once-in-a-generation transition that touches every facet of life, from the role of marginalized communities in political decisions to economic choices that will shape the country for decades. Sudanese are creating space to debate issues central to the idea of Sudan as a nation, such as the relationship between religion and the state. Recent months have seen the reentry of Sudan into the community of nations through growing international support for reforms and early efforts to address the country’s staggering debt burden in the wake of the December 2020 removal of Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism by the United States.

However, the country remains beset with economic crises and food shortages and citizens again took to the streets in recent weeks to protest rising costs and commodity shortages. Sudan faces continued conflict in Darfur, growing political unease in the east and the specter of regional war with Ethiopia. While the armed movements that have signed on to the peace accord have some constituencies, other movements that have yet to reach agreement with the government have significant support in areas like the Nuba Mountains. The COVID-19 pandemic proceeds unchecked, especially in urban areas. Questions remain among Sudanese and the international community about how long the rather delicate power-sharing arrangements between civilian leaders and military components of Sudan’s transitional government can be balanced.

The Potential of Politics

If the new Cabinet can rise to the occasion, it has a golden opportunity to become a model for political consensus-building and equitable decision-making in Sudan. Whereas the previous Cabinet’s ministers were selected for their technocratic capabilities and seemingly apolitical stances, this new Cabinet is arguably one of the most politicized governing bodies in Sudanese history.

Throughout Sudan’s post-independence history, political parties and armed movements have often been accused of not necessarily representing the interests of communities for which they purport to speak. If the Cabinet can agree on an agenda that prioritizes citizens’ needs, this can build faith in such groups while tempering potentially negative aspects of politics in government. Importantly, the Constitutional Declaration—the transition’s foundational agreement—states that ministers are prohibited from running in the elections planned at the end of the transition. However, part of the October 2020 peace accord was negotiated to allow for ministers representing the accord’s signatories to run in elections. It is hoped that regardless of this, breathing room is provided to focus on the transition’s urgent priorities and mending Sudan’s torn social fabric.

A united Cabinet can show that astute political leadership matched with continued reform of government institutions can produce a winning combination for managing diversity and preventing conflict in fragile states like Sudan. The Cabinet’s coherence and its ability to define roles among ministries and publicly articulate an agenda for the transition will be important for the overall functioning of the transitional government. This can also set a foundation for strong engagement with the international community on possible support and mutually accountable partnerships.

A well-functioning Cabinet can demonstrate to Sudanese that politicians are capable of governing and reduce the perennial unleashing of military coups that have plagued Sudan’s prior civilian governments. However, if leaders carry political conflicts and ideological rivalries with them into the Cabinet, this could decisively imperil an already tenuous transition and restart the cycle of conflict that Sudan and the region can ill afford.