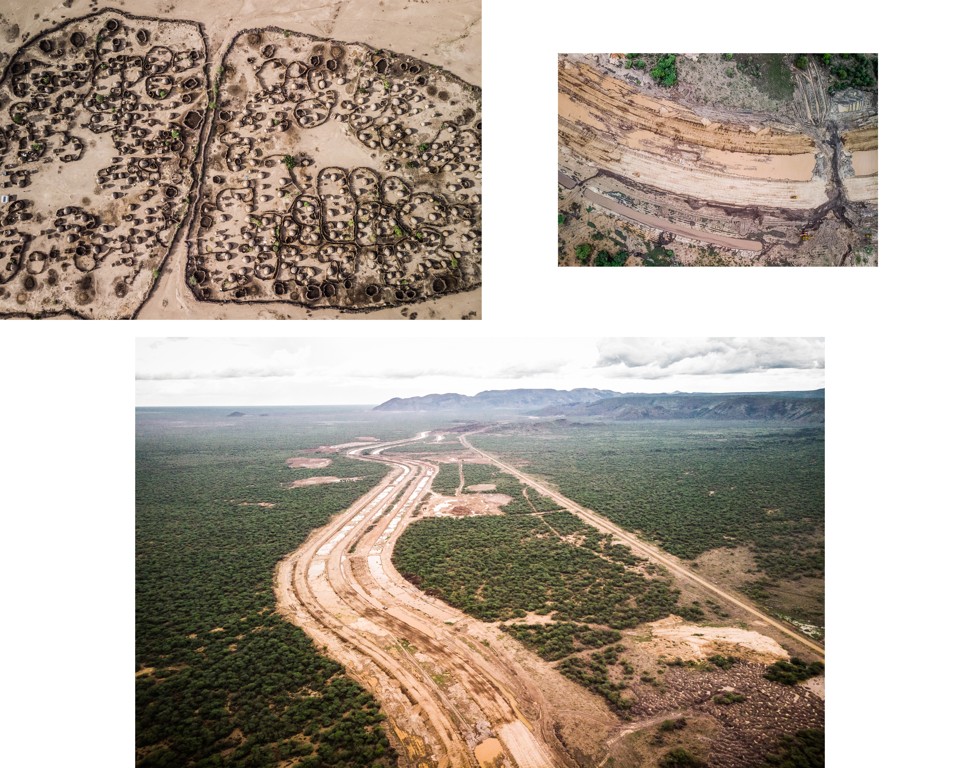

KANGATEN, Ethiopia—In Nyangatom, on the plains of the Omo River in southern Ethiopia, they call 2015 the “Year of China.” Around then, a bridge was built from there to Kangaten, the district capital, and CCCC (for China Communications Construction Company) appeared in giant blue lettering on the riverbank.

A few years earlier, a telephone tower had been erected at the edge of town. Then a two-lane highway constructed by a Chinese company started to unfold through the valley, toward the beginnings of a sugar factory and a vast irrigated plantation. The Year of China, locals say, was a period of development like nothing that they had ever witnessed. It was also the moment the river stopped flooding, and their world was altered forever.

More than half a million people depend on the lower Omo, which uncurls through southern Ethiopia, and on Kenya’s Lake Turkana, into which it flows. For millennia, the inhabitants of the Lower Omo Valley have survived on the fruits of the annual flood. When the river swelled, it brought fish upstream from the delta; when it receded, it left verdant soil for growing sorghum and maize, and rich pastures for grazing. Home to eight distinct ethnicities, including the Nyangatom, and to three of Africa’s main language groups, South Omo exemplifies the label Italian scholar Carlo Conti Rossini in 1937 gave Ethiopia: a “museum of peoples.”

But not for much longer. In 2006, hundreds of miles upstream, the Ethiopian government began constructing Africa’s tallest and arguably most controversial dam, known as Gibe III, with the help of a Chinese loan. The dam has the capacity to increase national energy output by 85 percent. It has another, more far-reaching, purpose as well. By regulating the river’s flow, it will feed the continent’s largest-ever state agricultural program, the Kuraz Sugar Development Project (KSDP)—almost as large as the total irrigated land area of neighboring Kenya. Together, Gibe III and KSDP represent the pinnacle of the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front’s (EPRDF) development ambitions. But by ending the Omo’s annual flood and, as a result, rupturing the fragile ecosystem on which the valley’s tribes depend, the project also raises a troubling question: Can the imperatives of a national economy ever outweigh the rights of a small minority to preserve its traditional way of life?

The government has long argued they can. In the past decade, it has embarked on Africa’s grandest infrastructure-building program, much of it financed by China, stacking up roads, dams, housing, industrial parks, and railways at a dizzying rate. State spending has powered economic growth of between 8 percent and 10 percent every year from 2004 to 2014, among the fastest in the world. But it came with a heavy social cost, triggering in recent years mass protests against land grabs, evictions, and home demolitions.

In the distant south, the government’s leaders echo the highland Ethiopians, who conquered the lowlands and annexed them to the Abyssinian empire in the late 19th century. They talk of bringing “civilization” to benighted backwaters, only this time through agricultural development. The idea of trade-off—that modernization might come with a cost—has rarely, if ever, been acknowledged. In 2010 then–Prime Minister Meles Zenawi accused critics, which included many international rights groups, of wishing to keep South Omo as an ethnographic zoo. “They want us to remain undeveloped and backward to serve their tourists as a museum,” he said at the time.

No one made a meaningful assessment of the project’s downstream impacts. And no one consulted with the valley’s inhabitants. “We don’t know why the water stopped,” Lokubal, who lives in a Nyangatom village, a stone’s throw from the border with Kenya, told me. “We’ve heard the Omo has been blocked somehow,” she said. “But we don’t know why; nobody told us.”

Some in Nyangatom blamed the Chinese, who are building the nearby sugar factory, Kuraz V, and in the preceding years, erected some of the surrounding infrastructure. Others, especially those with some education and living close to the town, criticized the government. But all—even those relatively far from the river itself—cataloged in sharp detail the devastating effects of life without the flood.

Lopiding, the chief administrator of Kajamikin village and an elder of some renown throughout Nyangatom, described it to me as a “potential death for our community.” He likened the river to a bank: “If you have a bank with all your money inside, and it is all taken, how can you survive? Omo is our bank. We could have everything from Omo.”

The project’s planners showed scant understanding of the environment they sought to master. In 2011, Meles gave a speech in which he called the flood a blight on the lives of the valley’s inhabitants. This was many miles from the truth, Desalegn Tekle Loyale, who grew up in Nyangatom and is now studying for his doctorate at Addis Ababa University, told me. “Unless there is flood, the Omo is useless,” he explained. “If there was a particularly large one, they would just move away towards the hills. The people think a larger flood means a larger harvest.”

By ending the annual flood, the planners set off a chain reaction, the effects of which are now plainly visible throughout the valley. For some, the consequences were existential from the outset. Many of those downstream, in the district of Dasenech, who are almost entirely reliant on flood-retreat farming and have little grazing land to fall back on, have been forced toward the delta, where the water is drying up. Claudia Carr, an anthropologist at UC Berkeley who has worked for years with the district, told me food is scarce and conflict over resources is intensifying.

“They’re wiped out along the river; they’re wiped out along the delta; they have nothing left,” she said. “When you’re dying and your family is dying, you’ve got to fight. You’ve got to fight over every last drop of water, every last blade of grass. And that’s the direction we’re heading.”

In Nyangatom, which has more cattle and more grasslands, the impact has been less explosive, so far. But in a world where climate change means more frequent droughts, the loss of the flood increases precarity. Already herders are traveling ever-longer distances in search of pastures. Lokubul’s son, for instance, has taken some of the family herd to South Sudan. “Look at our children,” she said, pointing at her youngest. “If there were cattle here, we would have milk to give them. But there are no cattle now; even the goats and sheep are not here.”

Almost the entire indigenous population of Nyangatom now depends on food aid. Some young men might find jobs on the sugar plantations, but certainly not all; a large portion of employees are migrants from outside the valley. Desalegn, who used to work as an engineer at Kuraz V before beginning his doctorate, fears that the people of South Omo’s future resembles the fate of Australia’s Aborigines, or of Native Americans: an impoverished version of their former lives, eked out on ever-shrinking communal reserves, dependent on state handouts. The valley is already witnessing a growing alcoholism problem.

Fana Gebresenbet, an academic at Addis Ababa University’s Institute for Peace and Security Studies, told me South Omo’s tribes face the prospect of assimilation or extinction. “It’s very likely that, if things continue like this, as a cultural group they will disappear over the next 20 years or so.”

On top of this, the chances of the KSDP eventually delivering on its promise of prosperity for all are slim. Since the spike in the mid-2000s, the global price of sugar has plummeted. Benedikt Kamski, a researcher at Freiburg’s Arnold-Bergstraesser Institute whose doctorate was on the KSDP, told me the project is simply too big to be successful. “They made too many mistakes in the conception that they can never make money off it,” he said. “That’s why it’s a white elephant.”

He argues that the time has come for activists—not just the government—to think seriously about alternatives and mitigation. “The developments there have reached a point of no return. The river is dead, and nothing will bring back the flood,” he said. Possible solutions might include sharing the profits from crops grown on the plantations with local communities, or—a proposal made by Nyangatom elites—allowing communities to tax the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation for the water it takes from the river. Meanwhile Fana, the academic, pointed to discussions around a new land law that could provide for communal ownership of lands that one day might be leased to investors by the communities themselves.

Some of this would require rethinking utilitarian assumptions about who benefits from, and who bears the cost of, national projects. To date, there are few signs of an intellectual shift of this nature inside the EPRDF, the ruling party. “In terms of the cost-benefit analysis for the locals … it is not comparable,” Ali Alemeyu, a local development agent in the Dasenech town of Omorate, admitted to me. “[The dam] is a benefit for the country; it brings electricity ... but really the priority should’ve been given to the local community. But that’s just my judgment—the government has already decided.”