Europe must join forces to govern immigration—supporting development in impacted African countries and integration in the most dynamic economies—because one country alone cannot end this problem, writes Attilio Moro.

By Attilio Moro

in Brussels

Special to Consortium News

Look at Via Merulana, in the center of Rome, between the two basilicas of Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni. On the street and the surrounding area, up to Stazione Termini (Rome’s central train station), groups of young Africans sell various trinkets. Others lay on the sidewalk, half asleep.

Look at Via Merulana, in the center of Rome, between the two basilicas of Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni. On the street and the surrounding area, up to Stazione Termini (Rome’s central train station), groups of young Africans sell various trinkets. Others lay on the sidewalk, half asleep.

One in three stores in the area are run by Bangladeshis. They sell to tourists small reproductions of the Colosseum, statues of Madonnas, religious calendars, and big pictures of the pope.

Bangladeshis, of course, are Muslim. Some of them are just employees. Some others have even taken this business over from Romans.

On one side of the street is Chinatown.

On the other, the posh neighborhood of Colle Oppio, overlooking the Colosseum.

The Bangladeshi and Chinese are established immigrants in this area. Africans are not. Most of them have just arrived. So newly arrived African immigrants and the Roman bourgeoisie live side by side—the former on the street, the latter in their villas.

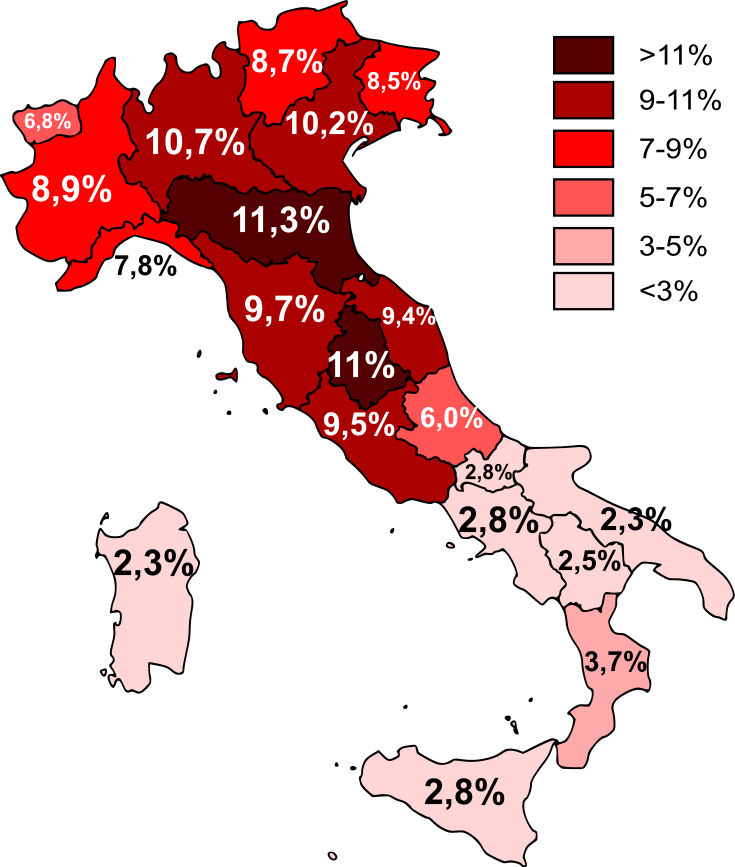

Foreign residents as a percentage of the regional population in Italy in 2011. (Wikipedia Based on data from http://demo.istat.it/)

Of course, the bourgeoisie of Colle Oppio are among the staunchest supporters of the hard line on immigration of the new Luigi Di Maio-Matteo Salvini government. But so are the inhabitants of the most deprived neighborhoods of Rome, where immigrants tend to concentrate, resulting in a sordid fight among poor.

This picture is typical in most Italian cities. Most of the young Africans here have arrived recently, rescued at sea by the marines of “Operazione Sofia,” or Operation Sophia, an Italian naval mission on the Mediterranean Sea, sponsored and paid for by the European Union.

Sophia was intended to destroy the smugglers’ vessels and rescue migrants in distress. In three years since it was launched, Sophia has destroyed 500 hundred small boats, which were meant to be lost any way by smugglers, who typically charge migrants 2,000-3,000 euros ($2,320-$3,480) just to take them to the nearest Sophia sea cruiser. Sophia also has left hundreds of thousands of migrants in Italian ports.

The Italian government at the time of the Sophia negotiations in 2015 agreed that the immigrants would be accepted exclusively in Italian processing centers (hotspots), considered to be the nearest from the Libyan coast, as established by maritime international law. Although for most vessels coming from Libya, the nearest ports are in Malta. Or sometimes in Spain.

The Result of Fiscal Irresponsibility

But why did the former government welcome all of them to the Italian ports of Pozzallo, Catania or Lampedusa? The answer is simple: Italy is the most indebted EU country after Greece, and has openly and persistently violated the Maastricht criteria—the rules that determine whether a country is ready to adopt the euro as its national currency—with a public debt at more than 130 percent of the GDP. (The limit, in order to remain in the euro, should be 60 percent). This means that Italy needs “understanding” from its European partners in order to keep running a high deficit and remain in the eurozone.

Syrian and Iraqi immigrants getting off a boat from Turkey on the Greek island of Lesbos. (Ggia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

From their side, the European partners are happy to condone illegal fiscal excesses on the condition that Italy keeps migrants from Libya within Italian borders. The agreement is similar to that between the EU and Turkey. For keeping migrants from Syria, Ankara is rewarded by the EU with 6 billion euros per year, or $6.9 billion. But while Turkey keeps them in refugee camps, Italy leaves them free, hoping that most will make their way to their final destination: Germany or France. But since both countries closed their borders, they remain stuck in Italy.

Instead of cooperating, European countries fight among themselves over immigration. In general, the EU still considers the mass immigration from Africa an Italian problem. Timid relocation schemes from Italy to other European countries have totally failed.

Germany and France now are only interested in keeping new immigrants out of the country. As a result, Italy is swelling with migrants and refugees, in an economy which has experienced little, if any, growth, reducing chances of decent integration to zero.

Needless to say, the failure of the European immigration policy has been a powerful boost for the so-called “populist” parties, who accuse former Italian governments of selling out political autonomy to Germany and the EU “elites” and for being responsible for this colossal failure, while blaming the traditional left for the current state.

Nicola Zingaretti in 2012. (Niccolò Caranti / Wikimedia)

The Future of the European Left

For the Italian (and most of the European) left, the question is: How do they react to this loss of political and cultural ground? How do they deal with such a complex (and epochal) problem? At stake is the destiny of the Italian and European left.

After years of passive orthodoxy, some people of the Italian left (among them Nicola Zingaretti, the probable next leader of the Democratic Party, the bulk of which is made up by former communists) are now trying a new, less ideological and more realistic approach. Pushing the issue of immigration onto the European agenda and making clear that no one, especially Italy, can cope with this problem alone. Not even if the EU shows some leniency for Italian fiscal profligacy.

The time of instrumental compromises over immigration is over. No more dubious deals can be made based on money. Europe should join forces to govern immigration, intervening to wind down African and Middle Eastern wars that create refugees and support development in impacted African countries, while offering real chances of integration in the most dynamic economies.

This will not happen in Rome, which is dealing with one of the worst crises of its (recent) history.

The solution is just common sense. But letting common sense prevail is difficult.

Attilio Moro is a veteran Italian journalist who was a correspondent for the daily Il Giorno from New York and worked earlier in both radio (Italia Radio) and TV. He has travelled extensively, covering the first Iraq war, the first elections in Cambodia and South Africa, and has reported from Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan and several Latin American countries, including Cuba, Ecuador and Argentina. Presently, he is a correspondent on European affairs based in Brussels.