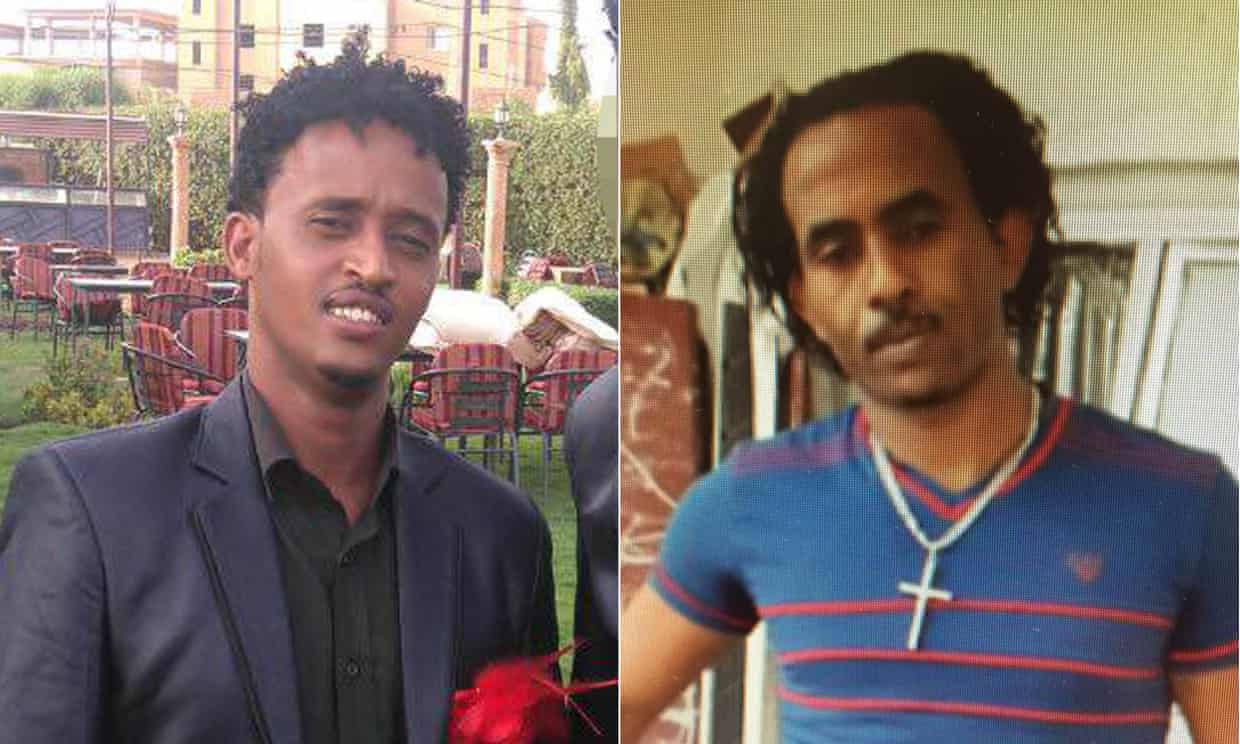

Medhanie Tesfamariam Berhe was milking cows on a farm near Khartoum when two police officers pulled a hood over his head, kicked him and forced him on to a flight from Sudan to Rome. The 30-year-old Eritrean refugee is on trial in Palermo, having been detained in Italy since 2016 – accused of being Medhanie Yehdego Mered, who is suspected of being one of the most sought after human traffickers in the world (aka “the General”). But Berhe is the victim of what must count as one of the most embarrassing cases of mistaken identity. Among the many factors that point to his innocence, including a DNA test and an array of witnesses, is a documentary by the Swedish broadcaster SVT in collaboration with the Guardian. It revealed that the “real” Mered is living it up in Uganda while Berhe, the farm worker, faces up to 15 years in jail.

This extraordinary case has never received the attention in the Italian press that it deserves. Any critical analysis of it seems even more remote a prospect now, with Matteo Salvini’s new far-right dominated government eager to prosecute NGOs that have spent the last five years at sea saving lives, for human trafficking. Yet, the “Mered” trial is not only the tale of a refugee mistaken for a smuggler. It symbolises a colossal failure; not just of an individual police operation, but an entire strategy pursued by EU governments of hunting down people smugglers as a way to deter people from travelling illegally to Europe, and keep immigration numbers down.

Led by Italian prosecutors, the hunt for Mered and his affiliates began after a shipwreck in October 2013, in which 368 people died a few miles off the Italian island of Lampedusa. The next day Italy and its allies in Europe declared war on human traffickers. The goal was to capture the smugglers who organised the crossings. Amid growing public disquiet about the arrival of thousands of migrants on boats each week, the idea gained immediate support.

News of Berhe’s arrest in June 2016, after an investigation led by prosecutors in Sicily that spanned two continents and five countries, was presented to the press as a brilliant coup for the new anti-trafficking strategy. Mered was apparently the first human smuggler to be extradited from Africa and regarded as the “Al Capone of the desert” by the authorities. The analogy with the American mobster isn’t coincidental. In order to capture the Eritrean, authorities in Palermo convinced their EU counterparts to join the crusade on a romantic premise: that the same tactics used to combat the Sicilian mafia in the 1990s could ensnare modern human smugglers – wire taps and the intuition that among smugglers lies a power structure regulated by a code of honour.

It is a captivating but flawed approach that has led to the arrest of countless innocents on the basis of contradictory evidence; Italy, for example, has imprisoned more than 1,400 migrants for piloting smuggling boats, even though they were forced to do this at gunpoint. The truth is smugglers are not mafia godfathers and there is no code of honour underpinning human smuggling. They are simply illegal travel agents, which is how refugees perceive them: a necessary evil in order to reach Europe. This reliance on smugglers is what prompted the decision to publicise every arrest of a smuggler. Take the case of Mulubrahan Gurum, arrested in 2015, in Germany. He was presented as the “cashier of the vast proceeds of human smugglers”. But it was later revealed that the transactions in his name amounted to three wire transfers for a total of about €600.

Prosecutors meanwhile eavesdropped on hundreds of people in countries in Africa, wire-tapping tens of thousands of conversations that brought to light little more than the cultural miscalculations of the investigators. Not only were they unfamiliar with the languages of the people who were recorded, but, as they admitted in an interview in the Swedish documentary, they did not know that these languages even existed.

The results were catastrophic: many Eritreans implicated themselves simply by mentioning common surnames while speaking on the phone. The investigators heard what they thought were the names of notorious smugglers, when Eritreans were talking about neighbours or the local greengrocer. Prosecutors even confused the word for “when” in the Tigrinya language (spoken in much of Eritrea) with the name of a man they thought was a powerful smuggler. This is the trap that Berhe found himself in, sharing one of the most common names in Asmara, Eritrea’s capital, with the true smuggler. On the day of Berhe’s arrest, Britain’s National Crime Agency, which collaborated with Italy on the arrest, published the news on its homepage with the headline: “Eritrean smuggler Medhanie arrested”. That would be like saying: “Irish man called Patrick arrested in Dublin”.

European authorities have also used selfies and other information garnered from people’s social media feeds as if they were bona fide IDs. Countless people may have ended up under investigation for having friended a suspected smuggler on Facebook. The obsession with arresting smugglers has meanwhile driven democracies to forge ties with authoritarian regimes, raising ethical questions: in order to extradite Berhe, the UK and Italy struck an agreement with Sudan, whose president, Omar al-Bashir, is the subject of an international arrest warrant for genocide.

Sicilian prosecutors insist that the man they captured is Mered, despite being unable to find a single witness to testify against him. In a country where migrants are increasingly perceived as parasites and invaders, this man is not only a probable victim of a miscarriage of justice, he symbolises a vast investigative system that has cost millions of euros and utterly failed to convict the human smuggler kingpins.

But sadly, admitting the failure of either this case or the broader strategy would be to acknowledge that European governments have grasped nothing of what really is at stake in dealing with migration.

• Lorenzo Tondo is a journalist based in Palermo, Sicily