Date: Tuesday, 16 January 2018

But some pampered royals have had enough of austerity

MANY Saudis saw in the new year by posting photos of their Starbucks receipts on social media. On January 1st the kingdom imposed its first-ever value-added tax (VAT), a 5% levy meant to help close a yawning budget deficit. It covers most goods and services, though sectors like health and public transport are excluded. (The United Arab Emirates did the same.) Some Saudis were angry about the higher cost of living. Others complained of being overcharged. But the reform, like others promoted by Muhammad bin Salman, the crown prince, went off with little real fuss.

Unveiled in December, the kingdom’s new budget of $261bn is its largest ever, a further reversal of a belt-tightening scheme imposed after oil prices crashed in 2014. Ministries had been ordered to slash their spending on new contracts by 5% in 2016, cuts that helped push the economy into recession. The new budget calls for a big boost in capital spending and an 11% bump in the health-care budget.

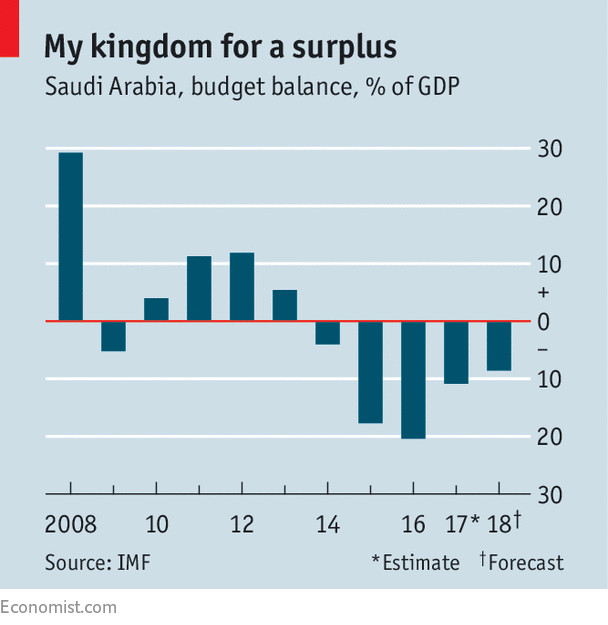

It also means a deficit of $52bn, or 7.2% of GDP. Though smaller than last year’s (see chart), that is still a hefty shortfall. Since 2014 the kingdom has drawn down more than $250bn of its foreign reserves. Though the central bank’s coffers have been replenished a bit in the past two months, reserves are still close to their lowest level since 2011. Saudi officials had hoped to balance the budget next year. The deadline has been postponed until 2023.

They may still struggle to meet that target. The VAT is expected to net just $6bn this year. A new fee on expatriate workers should bring in a similar sum. Fuel prices have been raised: the cost of the lowest-grade petrol is up by 83%. To cushion the blow, civil servants will receive an extra 1,000 riyals ($267) per month. Retirees and students will also get larger payments.

Oil revenues are expected to increase by 12% in 2018, to $131bn. Higher prices, though, will help less than before. Last year the government cut the tax rate on Aramco, the state-run oil giant, from 85% to 50%. The move makes the firm more attractive to investors ahead of a planned IPO. It also takes billions in annual revenue off the table. In the long term, Prince Muhammad wants to diversify the Saudi economy away from petroleum and the public sector. The budget assumes non-oil growth of 3.7% this year, more than double the rate in 2017. That may be too rosy.

One group that is not receiving new benefits is the royal family itself. As of January 1st the state stopped covering their utility bills. Three days later police arrested 11 princes who staged a sit-in at a palace in Riyadh, the capital. They were upset about having to pay for water and electricity for the first time in their lives. Among them were said to be two sons of the chairman of Almarai, a dairy conglomerate. His net worth is estimated at close to $4bn.

The squeeze on spoiled royals has helped to soothe public frustration. In November more than 200 royals and businessmen were detained in an anti-corruption sweep. Many have been released after handing over part of their wealth. In December Prince Muhammad was spotted on television talking to Prince Mutaib, a former head of the National Guard caught up in the purge. Days later Ibrahim al-Assaf, an ex-finance minister also detained, was photographed at a cabinet meeting. A few prominent names are still in gilded detention, notably Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, who holds big stakes in Citigroup and Apple. Authorities have reportedly set the price for his freedom at $6bn—or one year’s worth of revenue from the VAT.