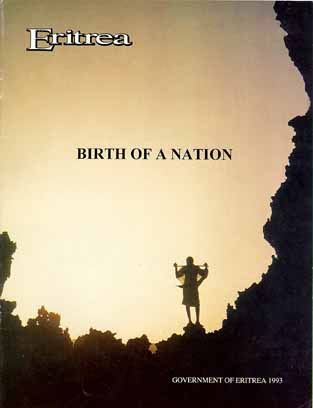

Cover: Afar nomad on a ridge of limestone stalagmites

Acknowledgments

The Government of Eritrea, Department of External Affairs, wishes to express their thanks to the following institutions and individuals who provided materials and granted permission to reproduce in this volume.

Angela Fisher and Carol Beckwith: Cover photo.

Government of Eritrea, Department of Culture and Information: All other photos.

Published in 1993 by the Government of Eritrea, Dept. of External Affairs, PO Box 190, Asmara

All rights reserved.

Contents

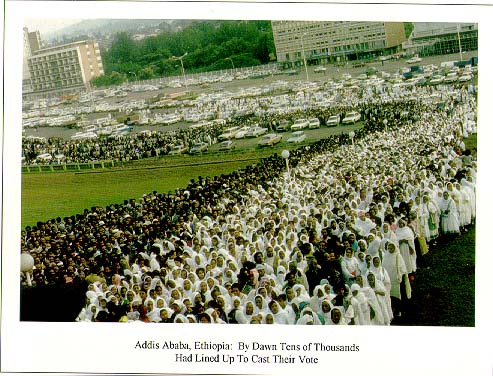

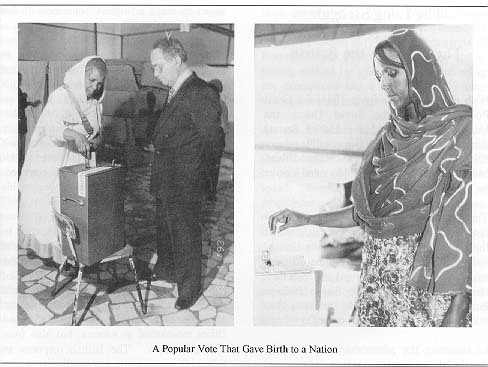

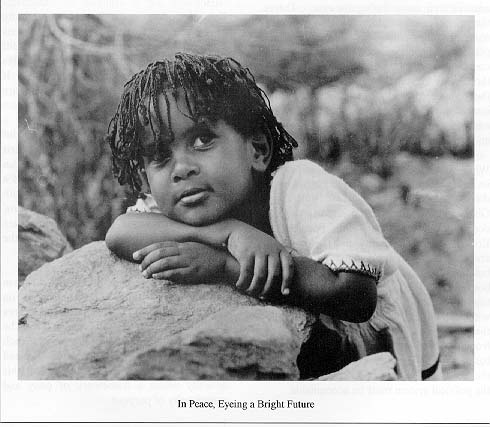

The final week of April 1993 marked the end of an era for the Eritrean people and with it the dawn of a new age. For close to fifty years, they had struggled tirelessly to achieve the fundamental right to determine their own destiny. Having won the right to define their status and chart their future, they voted with a single voice for independence in a referendum held from 23 -25 April 1993. The people of Eritrea have forever altered the course of Eritrean history and launched a new phase in the struggle for democracy, equality and freedom.

On 27 April 1993, the independent Eritrean Referendum Commission, the United Nations Observer Mission for the Eritrean Referendum (UNOVER), the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the Arab League, the Non-Aligned Movement, the National Citizens Monitoring Group and a host of individual observers issued their preliminary results following the three day vote on Eritrea's future. These organizations fielded over 500 independent observers. They were unanimous in their conclusion that the referendum had been free and fair.

The head of the UNOVER mission, Mr. Samir Sanbar, announced UNOVER's findings on 27 April. He said, "On the basis of the evaluation performed by UNOVER, I have the honour, in my capacity as Special Representative of the Secretary- General, to certify that on the whole, the referendum process in Eritrea can be considered to have been free and fair at every stage, and that it has been conducted to my satisfaction."

The Referendum Commission issued a preliminary report on 27 April. The total number of registered voters was 1,173,706. Voters totalled 1,156,280. With tendered ballots still uncounted, the Commission reported that 98.52 percent of those registered had voted. Of these, 1,100,260 (99.805 percent) voted "yes" for Eritrean independence.

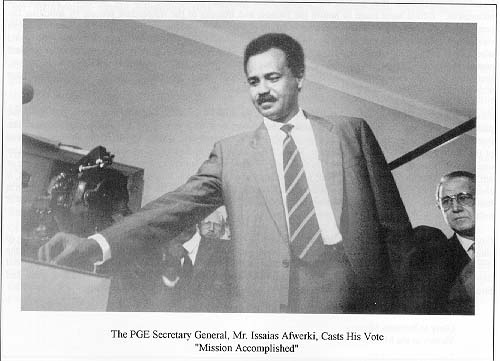

In the words of the Provisional Government of Eritrea (PGE) Secretary General, Issaias Afwerki, the referendum was "a delightful and sacrosanct historical conclusion to the choice of the Eritrean people. And although it has been decided that formal independence will be declared on 24 May 1993, Eritrea is a sovereign country as of today." (27 April 1993) Independent Eritrea was immediately recognized by several countries.

The Secretary General of the PGE further stated: "Congratulating the Eritrean people who have persevered with heroism, patience and civilized norms to shoulder their national responsibility and pay the heavy price of the lives of their best sons and daughters to make this democratic process a reality, I express my deepest thanks to the representatives of governments, international organizations and individuals who have participated in the observation process. I also wish that the new phase and future ushered in by this democratic choice will herald a period of enduring peace and prosperity.

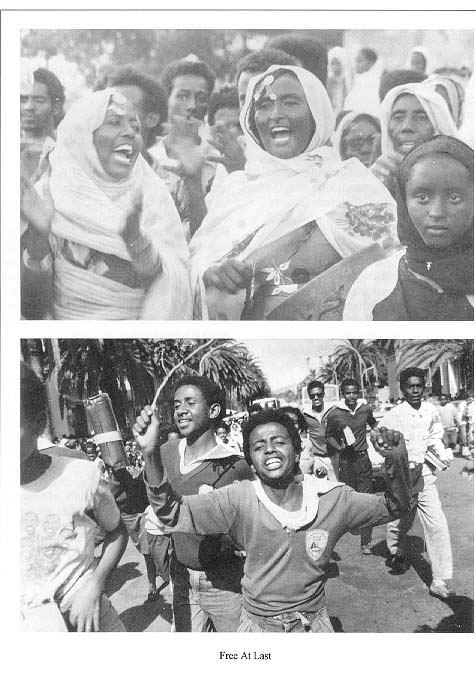

May 4, 1993, is the date of the official independence proclamation of Eritrea. Then, the national aspirations of the Eritrean people, demonstrated by their long struggle, commitment and sacrifice, finally became a reality. May 24 stands as the most significant of days in Eritrean history. It is also the date of the end of the war and the liberation of Eritrea. For generations to come, May 24 will mark a turning point in the lives of Eritrea's people. On this day, they won the ultimate reward for their struggle and sacrifice--freedom.

|

|

|

| The United Nations Observer Mission to Verify the Referendum in

Eritrea (UNOVER) was established pursuant to General Assembly

resolution 47/114 of 16 December l992.

The mandate of UNOVER was to verify the impartiality of the referendum authorities and organs, including the Referendum Commission, in all aspects and stages of the referendum process; to verify that there existed complete freedom of organization, movement, assembly and expression without hindrance or intimidation; to verify that there was equal access to media facilities and that there was fairness in the allocation of both the timing and length of broadcasts; to verify that the referendum rolls were properly drawn up and that qualified voters were not denied identification and registration cards or the right to vote; to report to the referendum authorities on complaints, irregularities and interferences reported or observed and, if necessary, to request the referendum authorities to take action to resolve and rectify such complaints, irregularities or interference; and to observe all activities related to the registration of voters, the organization of the poll, the referendum campaign, the poll itself and the counting, computation and announcement of the results. UNOVER deployed observers in all districts of Eritrea, and covered, from 23 to 25 April, most if not all, of the 1,014 polling stations. The core observer team, composed of 21 members from 21 countries, arrived in early February. They were joined the week before the vote by 100 UN observers. A total of 38 countries were represented. In addition, more than 40 observers were deployed in Ethiopia and in the Sudan to verify the vote of Eritreans in those countries. United Nations designated representatives also observed the referendum in several other countries including Canada, Italy, Saudi Arabia, the Scandinavian countries and the United States On the basis of the evaluation performed by UNOVER, I have the honour, in my capacity as Special Representative of the Secretary-General, to certify that on the whole, the referendum process in Eritrea can be considered to have been free and fair at every stage, and that it has been conducted to my satisfaction. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the Eritreans who helped UNOVER perform its mission. This of course includes the members of the Referendum Commission and the Eritrean authorities as well as all Eritreans. |

In mid-1991, the long conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia came to a close. The forces of the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) entered and liberated the capital of Asmara, dealing a final blow to the largest standing army in Africa. On 27 May 1991, the PGE was formed and announced its intention to hold a referendum on Eritrean independence within two years.

The next day, Ethiopian movements liberated Addis Ababa and unseated the ruthless regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam. The simultaneous victories of the Eritrean and Ethiopian peoples allowed for the peaceful settlement of the Eritrean question after three decades of war and repression.

The Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) convened a conference in Addis Ababa attended by 28 other Ethiopian parties and organizations. The participants voted to endorse Ethiopia's National Charter which, among other provisions, accepted the right of the Eritrean people to self-determination. They outlined the support of the new Transitional Government of Ethiopia (TGE) for the internationally-supervised referendum de-cided upon by the PGE.

On 7 April 1993, the PGE issued Proclamation No. 22/1992 on the Eritrean Referendum. The decree provided for an internationally-observed, free and fair referendum. It allowed "the people of Eritrea to freely and democratically decide whether or not they wished to become independent and thus conclusively determine Eritrea's status in the international community. " The question on the ballot would be "Do you want Eritrea to be an independent and sovereign country?" with the choices being "yes" or "no." The Referendum Proclamation specified that every Eritrean had the right to freely express his/her views on the issue. Eritreans and Eritrean associations in Eritrea opposing Eritrean independence were guaranteed the opportunity to express their views through meetings or the media.

Registration was based on the provisions of the Eritrean Nationality Proclamation (No. 21/1992). The PGE issued this decree before the referendum proclamation. Eritrean nationality was granted on the basis of several distinct qualifications. Any person born to a father or mother of Eritrean origin, in Eritrea or abroad, was entitled to citizenship. Special provisions were made for the many Eritreans of the Diaspora who, due to conditions of war in the country, possessed foreign nationalities. Provisions were also made for nationality by naturalization before and after 1952 (the onset of the federation period) and for nationality on the basis of adoption or marriage. The progressive nationality proclamation sought to provide eligibility in the broadest possible manner. It was extensively debated in the society and met with the approval of the population.

The organization of the referendum process represented an enormous task. This was undertaken by an independent Referendum Commission. After the identification of Eritrean citizens eligible to participate in the referendum process, the Referendum Commission began registering voters. The registration process involved extensive work not only in the urban and rural areas of Eritrea, but also in all countries where Eritreans reside abroad. The Referendum Commission appointed special representatives to act on its behalf abroad.

In Sudan, over 150,000 voters registered. Significant numbers of Eritreans registered in Ethiopia, the Middle East, Europe, the United States and Canada. Smaller numbers registered in other countries of Africa and in Australia.

Within Eritrea, the Commission established provincial offices distinct from government establishments. Simultaneously, the Com-mission identified sites for 1,007 polling stations. It erected simple structures, using local materials, for use in the voting process. Forty-five teachers were trained by the Commission. They, in turn, trained 5,000 young people who went throughout Eritrea as registrars.

An extensive public education campaign was launched. The provincial off1ces showed demonstration videos. The Commission explained the voting process to a population that had never participated in such an exercise. In early 1993, the Commission announced that any person or organization in Eritrea wishing to campaign for or against independence was free to do so. The campaign period began 17 February and extended to two days before the voting was to begin.

The PGE announced that all prisoners qualifying as having Eritrean nationality were free to vote in the referendum. On the basis of existing Eritrean law, they were considered innocent until proven guilty.

The international community played a significant role in supporting and observing the referendum. At the invitation of the Referendum Commission, a United Nations technical team arrived in Asmara in late July 1992. It was headed by Mr. Horacio Boneo, director of the election section of the UN Off1ce of Political Affairs.

In October, UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali recommended that the organization field a mission to observe the 1993 referendum. In his report to the General Assembly, the UN Secretary General said: "I conceive of (the referendum) not only as an important step towards the establishment of democracy but also as an integral part of the consolidation of peace. I am furthermore firmly convinced that this step can contribute decisively to the stability of the region. It is for these reasons, and taking into account the historical involvement of the United Nations with Eritrea, that I have decided to recommend the establishment of a United Nations Observer Mission to Verify the Referendum in Eritrea (UNOVER). "

In December 1992, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution authorizing the proposed UN participation. Early in 1993, the Secretary General appointed Mr. Samir Sanbar as his special representative and head of UNOVER. Working closely with the Referendum Commission, UNOVER established offices with full-time independent staff in Asmara, Keren and Mendefera. It fielded 120 international observers to ensure that the referendum was conducted freely and fairly. Participants in the UNOVER mission included representatives of a number of UN- member countries as well as experienced election observers.

Other members of the international community endorsed and participated in the observation of the referendum. Ethiopia sent a large delegation. Regional organizations -- including the Arab League, the Non--Aligned Movement and the OAU--and the governments of the United States, Canada, European countries, Australia and Japan also sent delegations. In September 1992, the OAU delegation in Eritrea commented, "We admire the tenacity and courage of the Eritrean people ... We saw a people with their shirt sleeves rolled up engaged in the reconstruction of a war-ravaged country ... The Eritrean people are very strong and Africa can learn from their courage and commitment.

Three distinct teams undertook the observation of the referendum. The UNOVER mission deployed 120 international observers. The Referendum Commission fielded 189 invited observers comprised of government officials, representatives of non- governmental organizations, academics and well-known international personalities. An Eritrean -based citizen's group also trained and, in coordination with the Commission, dispatched over 180 Eritrean observers.

The findings of the various observer teams reflected a consensus. The referendum had been organized and conducted in a free, fair and impartial manner.

|

|

Dear Compatriots, The Eritrean people were compelled to suffer an imposed and destructive war deprived as they were of their right to self-determination and statehood. But, after a bitter struggle and precious sacrifices, they have managed to express their democratic choice through a referendum conducted in the full presence of the international community. It is thus with boundless pleasure that I express on this momentous juncture and on behalf on the Provisional Government of Eritrea, my congratulations to the Eritrean people for their historic achievement. The express choice of the Eritrean people for full independence was never in doubt, and had indeed been long demonstrated without equivocation, through the peaceful and armed struggle that they waged for almost half a century. But although they were able to achieve their liberation two years ago in May 1991 by confronting the spiral of aggressive designs meted out on them to suppress their rights and crush their resistance, the victorious EPLF nonetheless refrained from declaring outright independence and opted to form a provisional government. This decision was taken because the EPLF was keenly aware that the issues of sovereignty and membership in the international community were predicated on a democratic and legal conclusion to the conflict. In this spirit, the EPLF decided that the free and fair choice of the Eritrean people would be determined through a referendum and formed an Independent Commission to carry out the task. Laws and regulations that govern the process were subsequently ratified and the necessary preparations undertaken. Efforts were made to ensure the fairness and freeness of the referendum process by soliciting the presence of observers as well as the active participation of the United Nations. And in spite of the hostile attempts carried out to deny the Eritrean people this historic opportunity and to impede the participation of observers--and especially to prevent the participation of the United Nations, the Organization of African Unity and other regional organizations--the referendum process elicited in due time the international response that it merited. Moreover, thanks to the full cooperation of the Eritrean people, the preparations and organization of the referendum were accomplished peacefully and with least expenditure by all standards. As earlier announced by the Referendum Commissioner, the preliminary result of the referendum carried out in the past three rainy days with gratifying enthusiasm and propriety is 99.8 percent in favor of independence The freeness and fairness of the process has been certified by the observers and notably by Mr. Samir Sanbar, the Head of the United Nations Observer Mission to Verify the Referendum in Eritrea. This outcome is not surprising or unexpected. Indeed, the issue at stake was not some political contest but the very survival, the question of to be or not to be, of a people. As such, the result was obvious and a foregone conclusion from the outset. In the event, it constitutes a delightful and sacrosanct historical conclusion to the choice of the Eritrean people. And although it has been decided that formal independence will be declared on 24 May 1993, Eritrea is a sovereign country as of today, April 27, 1993. Finally, congratulating the Eritrean people who have persevered with heroism, patience and civilized norms to shoulder their national responsibility and pay the heavy price of the lives of their best sons and daughters to make this democratic process a reality, I express my deepest thanks to the representatives of governments, international organizations and individuals who have participated in the observation process. I also wish that the new phase and future ushered in by this democratic choice will herald a period of enduring peace and prosperity. Glory to Eritrean Martyrs |

The struggle for basic democracy in Eritrea was launched over half a century ago as the era of European colonialism on the continent came to a close. Before the European colonial period, Eritrea's 1,000 kilometer coastline attracted a range of foreign powers. It offered both a key strategic position as well as significant opportunities for trade. The Turks controlled the Red Sea coast in the 16th century, followed by the Egyptians in the 18th century. In the modern era, the Italians, British and Ethiopians occupied the country.

Each of these foreign interventions had a distinct impact on the development of Eritrea as a nation and in the formation of an Eritrean identity. None, however, was as significant as the Italian colonial period, which extended from 1880-1941. This was the era during which Eritrea emerged as a distinct territory.

Italy moved to transform Eritrea, with its access to the sea and agricultural potential, into a permanent colony. The king of Italy issued a decree formally establishing Eritrea on 1 January 1890. Italian immigration to Eritrea began at the turn of the century. By the close of the Italian colonial period, about 70,000 Italians had settled in Eritrea.

Economic expansion was central to Italy's goals. The Italian government therefore moved to gain control over land, the most vital of resources. By the late 1920s, the Italians claimed more than half Eritrea's land as their own. This included all roads, sea shores, ports, forests, rivers and river banks, mines, all land not inhabited by sedentary people, and significant portions of the eastern and western lowlands. Known as "Crown" land, these areas fell under the complete legal and administrative control of the government of Italy. The Italians also converted significant portions of land formerly belonging to the Orthodox Church to Crown land. They assumed control of some of the most fertile areas of the country while diminishing the church's economic power.

Most Eritreans depend on the land for survival. Thus, Italian intervention in traditional land-holding and cultivation systems had a significant economic impact on the Eritrean people. Faced with the new scarcity of arable land, many sought employment elsewhere. The introduction of mechanized agriculture and commercial farming generated a new demand for wage--based seasonal labor.

Italian agricultural policy was designed primarily to benefit the settlement population and to sustain Italian exports to Europe and East Africa. The Italians introduced new cash crops--including cotton and tobacco -- and improved crops and techniques. There was a dramatic shift in labor patterns and the livestock sector expanded. Each of these shifts had an impact on Eritrea's social and economic development during the years to come

The development of a market-based economy required that the Italians upgrade Eritrea's infrastructure, previously based on the simple needs demanded by a subsistence economy. The relatively extensive com-munications and transportation facilities established were among the best in Africa during this era. They served both to expand Eritrea's trade capacity and to unify it economically and socially. The Italians built railway lines between Asmara and Keren and between Keren and Agordat. The port of Massawa was linked by rail to the interior. All- weather roads were constructed through the mountains of Eritrea and across the lowlands. Two modern airports were built. An export-based industrial sector was created and Eritrea forged new links with the international economy.

This rapid expansion of infrastructure and modernization of the economy occurred over only two generations. It had a dramatic impact upon the population. By the 1940s, a previously rural-dominated population had developed a significant urban sector. During this period, urban dwellers swelled to over 20 percent of the total population.

National identity and, gradually, a national consciousness developed during this era. People from diverse economic, ethnic and religious backgrounds were structurally linked within the colonial borders. Their experiences differed sharply from those of their neighbors in Ethiopia. Ethiopia remained dominated by a feudal economic system managed by imperial rule. By the 1940s, Eritrea had developed a substantial working class as well as a distinct urban--based intelligentsia. Access to information about world events was enhanced by the presence of Italy and Italian settlers, and by the expansion of trade and international exchange.

Italian colonization played a significant role in charting the course of Eritrea's economic future. It resulted in the partial development of an Eritrean economy. Nevertheless, Italian colonial rule was not benign. The Italian administration reflected the views and aspirations of a fascist government. Eritrea's people were seen as little more than a source of cheap labor to fuel the aims of Rome. There was a forced labor law. Eritreans played only subsidiary roles in their country's economic and political development.

The Italian colonial economy was, of necessity, a war economy. Italy participated in two major conflicts during its rule of Eritrea. In 1896, Ethiopia defeated Italy in the Battle of Adua. Eritrea experienced the first phase of militarization when Eritrean citizens were pressed into action in the Italian colonial army in that war. However, the more significant phase of militarization took place during World War II, when Eritrea was employed as a base for attempted Italian expansion. Thousands of Eritreans were conscripted into the Italian forces, enticed by special benefits including tax exemptions and employment at a time when jobs were scarce.

An era of economic deprivation for the people of Eritrea followed Italy's defeat in the Second World War. The rapidly-built colonial economy deteriorated with relative speed. Former soldiers with no hope of employment, but continued access to guns, returned to their homes. Italian industries slowly fell into decline. The highly--dependent commercial agricultural sector gradually collapsed. Economic deterioration generated high unemployment for the expanded urban class. Rural dwellers still faced problems provoked by the continued scarcity of land.

The Long Struggle for Freedom: The Reign of the

British

With the defeat of Italy in 1941, the Great Powers (France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States) decided that Great Britain would govern Eritrea as a protectorate. The British Military Administration (BMA) ruled Eritrea as "Occupied Enemy Territory. "

The BMA wanted to rid Eritrea of Italian fascist rule while maintaining recognition of the right of the Italian state to rule Eritrea. Italian administrators and traditional Eritrean rulers were gradually replaced by their British counterparts. The Sudan Defense Force (SDF) was brought in as a key instrument of British administration

In assuming the administration of Eritrea, Britain inherited an economy in collapse and a society poised to begin the long struggle for freedom. The population of Asmara had more than quadrupled in size. Significantly, the British exercised no jurisdiction over the Crown land so most of Eritrea's land continued to be exploited by non-Eritreans. Landless peasants, increasingly frustrated by the dearth of economic opportunities, turned to rebellion, igniting a period of resource--based conflict between Eritrean rural dwellers and Italian farmers.

Many viewed the British as a welcome respite from Italian fascist rule. Nonetheless, Eritrean society was by then experiencing the first stirring of the desire for self--determination. Peasant resistance had in-creased during the final years of Italian governance. The economic hardships suffered because of the dominance of foreign agendas began to make Eritreans conscious of the need to chart their own economic future.

Until this period, Ethiopian involvement in Eritrea was quite limited. From the turn of the century through the onset of British military rule, Eritrea and Ethiopia moved on separate economic and political tracks. Eritrea developed a colonial-based market economy while Ethiopia maintained feudalism. By the 1940s, however, Ethiopian designs on Eritrea clearly emerged. The newly-reinstated Emperor began his effort to gain influence and control.

Ethiopia employed three primary tactics to achieve its goal of increasing influence and domination. These were interference in the religious affairs of Eritrea, manipulation of political parties and organizations, and terrorism. Ethiopia's efforts were carried out primarily through the Ethiopian Liaison Office established in Asmara, but also from within Ethiopia. The British response to Ethiopia's increasingly interventionist stance was largely ineffectual. Although skeptical of Ethiopia's ability to govern Eritrea, the British remained unwilling to allow Eritrean governance. They were unable to counter the growing disruption generated from Addis Ababa

With the departure of the Italians, the Eritrean Orthodox Church reinstated its ties with its Ethiopian counterpart. Once a powerful landowner in Eritrea, the Orthodox Church had lost significant holdings during the Italian era. It hoped to regain land and power by recreating its links to the still feudal Orthodox Church in Ethiopia.

According to one European historian, "By 1942, every priest had become a propagandist in the Ethiopian cause, every village church had become a center of Ethiopian nationalism, and popular religious days ... had become occasions for open displays of Ethiopian patriotism." The Ethiopian Church, and the regime with which it was allied, continued to denigrate Islam. Ethiopia promised the return of land to the Eritrean Church once the two countries united, and supported the church's struggle to regain its economic power base. By the mid- 1940s, the church was refusing to conduct baptisms, marriages, funerals or other religious services for any Eritrean who did not support unity with Ethiopia.

The era of "democratization" heralded by the end of the Cold War is often regarded as the beginning of a new trend in Africa. However, in Eritrea the emergence of active political parties can be traced to the period of British administration. The Eritrean people knew that the British presence was likely to be temporary. They were also aware that a new foreign power--Ethiopia --was positioning itself to rule their lives. It is in the context of growing Eritrean consciousness and increasing Ethiopian expansionism that the struggle for Eritrean independence emerged.

During the same period, political parties were born. The Party of Love of Country (PLC) first emerged as an anti-colonial movement. Gradually those favoring in-dependence and those advocating unity with Ethiopia developed differences. The Ethiopian government undermined attempts by PLC leaders to reach a consensus. In the words of an official BMA representative, "Party leaders were no longer free agents. They had become servants of the Ethiopian Government. "

During this critical stage in Eritrea's history, five main political parties emerged. Four-- the Moslem League, the Liberal Progressive Party, the Pro- Italian Party and the National Moslem Party of Massawa -- favored independence. The Unionist Party favored unity with Ethiopia.

Ethiopian-sponsored terrorism appeared simultaneously with the rise of political parties and the increase in the power of the pro-independence coalition. Small-scale shifta (bandit) attacks, directed at Italians and less frequently at the British, spread during the late 1940s. They gradually began to disrupt the already weakened rural economy. Soon the attacks were directed at Eritrean nationalists. Repeated attempts-- some successful--were made on the lives of independence leaders.

Several times the BMA traced financial support for the shiftas to the Ethiopian Liaison Office in Asmara. The UN later wrote, "Terrorism had developed in Eritrea to support a (Unionist) policy. Some people who were opposed to annexation of the territory to Ethiopia had been subject to terrorist attack on their person and property. Others, out of fear, have been compelled to follow the party which followed annexation to Ethiopia."

The end of World War II resulted in UN oversight of the fate of the former Italian colonies -- Eritrea, Libya and Italian Somaliland. By this time, the BMA was finding Eritrea difficult to govern. Ethiopia was staking a claim through intervention and flurried, though largely unsuccessful, diplomatic efforts. The United States, which had maintained a presence in British- administered Eritrea, was showing increasing interest in obtaining a strategic presence on the Red Sea coast. Nevertheless, a US official based in Asmara advised, "I have yet to meet a foreigner thoroughly familiar with conditions here who considers that the present Ethiopian Government is competent to give Eritrea a reasonable, efficient administration."

The discussion that was to define Eritrea's future for the coming forty years began in April 1949 in New York. Various proposals --partition, annexation and independence -- were debated. The Eritrean people clearly favored independence. According to the British, 75 percent of the population supported independence.

On 2 December 1950, the UN passed a resolution that formally federated Eritrea to Ethiopia. In September 1952, the agreement was put into practice and Ethiopians replaced the British.

According to the terms of the resolution, Eritrea was to be "an autonomous unit under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Crown." It would enjoy "the widest possible measure of self-government." The Ethiopian emperor pledged his commitment to rule Eritrea as a constitutional monarch.

The international decision regarding the fate of Eritrea had little to do with the aspirations of the Eritrean people themselves. The Americans, British and Italians knew that most Eritreans favored independence.

By the early 1950s, the Americans were active players in the Cold War . John Foster Dulles, the former US Secretary of State, stated their position on Eritrea in this way: "From the point of view of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country has to be linked with our ally, Ethiopia."

America's primary interest was in taking over the British communications center situated on the outskirts of Asmara. During the 1950s and 1960s, Kagnew Station grew to become the largest American intelligence gathering site outside the US. It eventually housed 3,500 American personnel. In ex-change for US use of Kagnew, the Ethiopian government received close to one-third of all American assistance to Africa. Much of the military assistance and training was later used to fight the Eritrean Liberation Front.

During the federal period Eritrea functioned with its own constitution and with an elected assembly. However, Ethiopia's desire for total control remained unsatisfied. The involvement of the emperor increased during the first year of the federation. Ethiopia deployed two army divisions to Eritrea and the battle for Eritrea entered a new stage.

In the face of increasing intervention by Ethiopia, democratic political activity in Eritrea expanded in the 1950s. The Ethiopian emperor gradually whittled away the power of the Eritrean administration. He violated the constitutional rights of the Eritrean people by banning trade unions, closing newspapers, overruling court decisions, banning local languages, and, finally, employing brute force. Political leaders were forced into exile or imprisoned. Open resistance to Ethiopian rule grew in direct proportion to Ethiopian attempts to constrain Eritrean political participation.

By the end of the decade, Ethiopia made clear its intent to bring Eritrea under complete Ethiopian domination. In 1959, the Eritrean Assembly voted, under duress, to adopt the Ethiopian penal code. The following year, the "Eritrean Government" became the "Eritrean Administration. " In 1962, Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie issued Order No. 27 declaring "the federal period is hereby terminated. "

Ethiopia had annexed Eritrea in violation of international law. Successive Ethiopian governments based their claim to Eritrea on the Eritrean Assembly's endorsement of these measures. However, coercion, not democracy, was the decisive factor. Political activists, journalists, trade union organizers and students were arrested. Police were present in the Assembly, which was surrounded by Ethiopian military forces during critical votes.

In the words of the then-US Consul in Asmara, "The 'unification' was prepared and perpetrated from above in maximum secrecy without the slightest public debate or discussion. The 'vote by acclamation' was a shoddy comedy, barely disguising the absence of support even on the part of the Government-picked Eritrean Assembly."

While the United Nations bore responsibility for the legal implementation of the 1952 resolution, neither the UN General Assembly nor any of its members protested Ethiopia's outright violation of international law. International silence in the face of Ethiopia's continued efforts to rule Eritrea illegally and by force characterized the next phase of Eritrea's history.

In the face of Ethiopia's increasingly successful effort to prevent popular political activity in Eritrea, little alternative remained but for the people of Eritrea to turn to armed struggle. The Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) led the armed struggle in its early stages. It comprised a small group of combatants, Eritrean intellectual leaders based outside Eritrea, and some nationalist politicians from the 1950s. Increasingly, students and workers joined the ELF. Despite the ELF's relatively small size when it launched the armed struggle in September 1961, the Ethiopian imperial government answered with forceful reprisals, many aimed at civilians.

By the late 1960s, acute differences emerged within the ELF. Some favored a combined political and military approach to the struggle. They stressed the need for the politicization, development and participation of the society. Others had no clear strategy and resorted to harmful and divisive practices. Internal conflict deepened in another, broader dispute regarding Eritrean unity. One group felt the war should be organized according to existing religious and ethnic structures. The opposing view was that the struggle should enhance the unity of Eritreans of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds by encouraging joint participation and exchange.

In 1970, internal differences led to the emergence of the EPLF. Its twin goals were independence and social change. It advocated an integrated approach to Eritrean unity. At the leadership level and among the rank-and-file, the EPLF continues to reflect the diversity of religions and nationalities in Eritrea.

In one of the most painful segments of Eritrea's recent history, the ELF and EPLF fought a brief civil war that resulted in the ELF's defeat. Eventually, almost all of the leaders and members of the various factions that emerged from the ELF joined the EPLF, or the PGE following Eritrea's liberation in May 1991. There were no differences among Eritreans on the goal of national independence.

The armed struggle in Eritrea is best viewed in distinct phases. During the 1970s, the Eritrean movements grew in size as rural dwellers as well as students and workers joined the ranks of the armed opposition to Ethiopian rule.

In 1974 the Ethiopian emperor was deposed following defeats in Eritrea and increasing popular discontent with authoritarianism and feudalism in Ethiopia. However, the political vacuum that existed in Ethiopia at the time, allowed the military to step in and take over the government.

For a brief period, there was hope that the Eritrean question might be settled by peaceful means. Some members of the new government expressed interest in negotiating with the Eritreans. They were killed by a young lieutenant named Mengistu Haile Mariam

Mengistu eventually gained control of the Provisional Military Administrative Committee or "Dergue" as it was known in Amharic. Mengistu and his followers had little interest in peace. By 1976, their position was clear: Eritrea was to remain part of Ethiopia even if they had to impose unity by force.

Force, as defined by the Mengistu regime, meant an intensification of the war and the use of a policy of state terrorism, particularly in urban areas. In January 1975, for example, 100 young people were strangled with wire by Dergue authorities in Asmara. In March, another 500 residents were killed.

The war gained considerable momentum m the mid-1970s. Eritrea's freedom fighters consolidated control of the countryside and then liberated most of Eritrea's major cities save Massawa, Asseb and Asmara. By 1977, Ethiopia was on the brink of defeat in Eritrea. It was only saved by a quirk of history.

As the Eritrean movements intensified their challenge to the Ethiopian military, Somalia invaded the Ogaden region along the Ethiopian-Somali border. The Mengistu government, which had little success in maintaining the support of Washington, turned instead to the Soviet Union. The USSR was eager to develop a relationship with the self-described Marxist government. It quickly abandoned its position in Somalia and shifted allegiance to Addis Ababa. Simultaneously, the US government, under the leadership of former President Jimmy Carter, curtailed its already weakened relationship with Ethiopia and adopted Somalia as its regional ally. This "super-power shift" had more to do with the politics of the Cold War than with the realities of the region, but it had significant impact upon regional developments.

Over the next 17 years, the Soviet Union provided Ethiopia with the equivalent of US $12 billion in military training and equipment. It encouraged the significant support of its allies in the Eastern Bloc and Cuba. Soviet firepower, ostensibly requested to fend off the Somali invasion, was quickly deployed against the Eritrean movements. Soviet naval forces attacked along the Red Sea coast. Eritreans were subjected to the most massive aerial bombardments experienced until that time. Faced with a war of a new scope and nature, the EPLF made a strategic withdrawal from the cities it administered and moved to adopt a new strategy.

Between 1978 and 1986, the Ethiopian army launched eight offensives against the Eritrean freedom fighters. Each used greater fire and labor power than the last. None were successful.

The EPLF shifted from its pre-1978 strategy to one based on the development and defense of an extensive rear base area in the northeast Sahel area. They constructed an extensive network of trenches. The conflict shifted from mobile guerrilla to conventional warfare.

During this period, the EPLF expanded dramatically. Large numbers of men and women, most hailing from the rural areas, left their homes to become EPLF fighters. Significant victorious battles at Tessenei, Ali Gidir and Mersa Teklai in 1984 resulted in the capture of a wide array of sophisticated Soviet-supplied weaponry.

The Dergue carried out a policy of forced national conscription, which swelled the ranks of the Ethiopian army. By the early 1980s, it deployed most of its forces to the Northern Command.

In the infamous "Red Star Campaign," or sixth offensive, of 1982, Ethiopia sent over 100,000 infantry soldiers to Eritrea. The Mengistu regime billed the campaign as the final offensive against "bandits" and "Arab invaders from the north." However, Red Star was a dismal failure. The EPLF successfully repelled repeated Ethiopian attempts to break the Sahel defense lines and soon opened new fronts to the west.

The failure of the Ethiopian army in this and other offensives largely derived from Mengistu's forced conscription policy. It left him with poorly trained and ill-informed soldiers who were no match for the EPLF. At times during the war, the EPLF cared for as many as 10,000 Ethiopian prisoners of war. Most of them were poor peasants who had no idea why they were fighting and little knowledge of the truth regarding Eritrea.

In sharp contrast, the EPLF could defeat a much larger and better-supplied army. It marshaled the sacrifice and commitment of its fighters and the participation of the Eritrean people. It re-deployed captured weapons against the enemy.

In 1988, the war took another decisive turn when the EPLF liberated Afabet, the headquarters of the Ethiopian army on the northeastern front, and moved forces into the area around Keren, Eritrea's third-largest city. The battle was a decisive military and psychological defeat for the Dergue. It yielded massive amounts of weaponry and supplies for the EPLF.

Early in 1990, the EPLF attacked the Red Sea port of Massawa from land and sea. It liberated the city in three days. The Ethiopian Air Force bombed Massawa without interruption for the following six months. Nonetheless, the EPLF maintained control of the city and moved to initiate the final phase of the war.

Simultaneously, Ethiopian movements intensified their own military struggle against the Ethiopian army. Despite its numbers and the extensive assistance supplied by the outside world, the government troops met with repeated defeat on multiple fronts. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Dergue lost its mainstay of support. The beleaguered army could not stand on its own.

Early in 1991, parallel offensives in Eritrea and within Ethiopia drove the Ethiopian army from its remaining positions. In May 1991, the EPLF liberated the Eritrean cities remaining in Ethiopian government hands. On 24 May 1991, the capital of Asmara was liberated in the final victorious battle. Ethiopian troops fled the city or gave up their arms in haste. Within minutes of the EPLF's entry into the city, Asmara's residents poured into the streets to hail and welcome the fighters of the EPLF. Three days later, the Ethiopian army lost its final battle in Ethiopia, and the EPRDF took the capital, Addis Ababa.

Upon entering Asmara, the EPLF found a population ecstatic with victory and freedom. The city had been under a dawn-to-dusk curfew. Basic utilities had deteriorated or been totally shut down. The once-elegant city had not been maintained. Evidence of occupation and hardship was apparent everywhere. Similar conditions existed elsewhere in areas of Eritrea occupied by the Ethiopian regime. Within hours of victory, the long struggle for reconstruction was launched. Free At Last

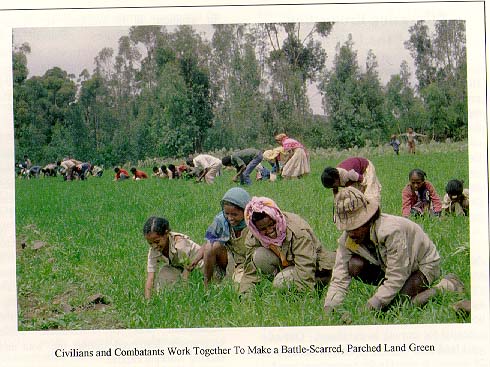

The EPLF was created as a political organization employing military means. Its goals were never restricted solely to winning the war. As an integral part of its strategy, the EPLF pursued political as well as socioeconomic goals during the armed struggle.

Politically, the EPLF organized local communities to participate actively in their daily affairs. Village-level assemblies were elected in all EPLF- administered areas and bore responsibility for their own governance.

These local structures also provided the basis for the implementation of the socioeconomic objectives of development. Conditions required that local committees frequently engage in the administration of relief programs. Nevertheless, considerable effort was also made to develop agricultural programs and water resource projects, and to provide basic education and health services

Self-reliance was a prominent theme throughout the war. The EPLF educated its fighters and provided for their needs by constructing factories in the base area and by developing extensive medical and educational facilities. Central to the EPLF's program was the view that the development of Eritrean society could not wait until after liberation. It must serve as a key objective of the liberation process itself. The EPLF was organized to include not only military departments but also sectoral departments of health, education, agriculture, transportation and others. EPLF fighters were barefoot doctors, teachers, mechanics, extension workers and technicians as well as combatants.

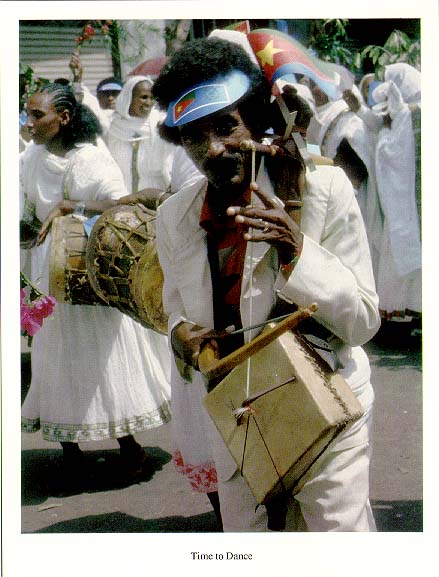

Eritrean culture also played a central role. Cultural troupes performed the music and dances of each of Eritrea's nine nationalities. Drama was a means to organize and educate people. In the midst of a major war, a radio station, newspapers, journals and film and broadcast facilities were developed. Information services were provided to the people in several of Eritrea's languages.

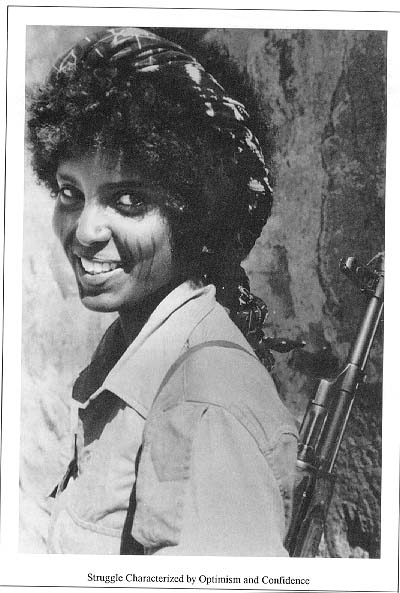

The role of women in the struggle was substantial and critical to the ultimate success of the EPLF. Women comprised over 25 percent of combatants. They rose to positions of leadership in the military and politics. The National Union of Eritrean Women organized and facilitated the participation of civilian women in the struggle. It implemented programs in basic health care, literacy, and training to serve their needs. Women were a significant proportion of the assembly members elected in EPLF-administered areas.

The long war in Eritrea unfolded in international isolation. In the early years, Haile Selassie was popular with the West. He was willing to provide the US, Great Britain, and other countries with military facilities. This ensured that the West came down on the Ethiopian government's side.

With the 1974 change of government in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia shifted from the West to the Soviet camp, but the Eritrean conflict remained unrecognized in the eyes of the international community. Soviet support flowed to Addis Ababa, matched by significant military assistance from Libya and South Yemen as a result of a Tripartite Agreement signed in 1980.

Western military support for Ethiopia dwindled, but Western economic assistance to Ethiopia reached its highest level during the Mengistu period. Israel, which had supported the Haile Selassie government and trained special commando units deployed in Eritrea also supported the Mengistu regime.

The primary obstacle to recognition of the Eritrean conflict was the Cold War. The US and USSR forged alliances based on national interests, with little regard for local realities. Despite the legal basis for Eritrean self-- determination and the illegal violation of the UN federal agreement, no government formally recognized Eritrea's right to self--determination until the war's end in 1991.

Multiple reasons were given for denying Eritrean self-determination. Some members of the international community strongly supported Ethiopia's groundless contention that access to the Eritrean Red Sea coastline was necessary for the survival of the Ethiopian state. Others argued that an independent Eritrea would not be economically or politically viable, though no concrete evidence was given to support this view.

A central and repeated argument was the fear that Eritrean independence would trigger the disintegration of other African states, in particular Ethiopia. A provision of the OAU Charter that states its determination to "safeguard and consolidate .. the sovereignty and territorial integrity of our states" underpinned this view. In fact, the OAU Charter was largely the work of the former Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie. He oversaw the creation of the organization just two years after he annexed Eritrea with no objections from the international community. Ironically, the stipulation in the OAU Charter that colonial boundaries be respected supported the Eritrean claim to self- determination. Eritrea's borders were delineated during the Italian colonial period.

A few unsuccessful efforts were made to achieve a negotiated peaceful settlement to the Eritrean conflict. In 1980, the EPLF issued its own peace plan, calling for an immediate cease-fire followed by an internationally- supervised referendum. Ethiopian authorities rejected the proposal out of hand. This followed earlier attempts by Cuba and the Eastern Bloc countries, led by East Germany, to negotiate solutions to the underlying political problems. In 1989, former US president Jimmy Carter attempted to negotiate between the EPLF and the Mengistu government. However, successive meetings in Atlanta and Nairobi failed to yield progress. As made clear in his final speeches, Mengistu Haile Mariam was determined until the end to pursue the slogan "Unity or Death" whatever the costs to the people of Eritrea and Ethiopia.

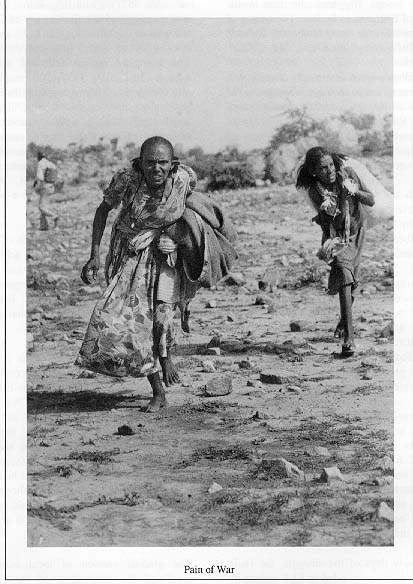

Thirty years of war brought dire con- sequences for the people of Eritrea. The population was affected in four major ways. A cycle of famine developed and intensified. Thousands of Eritreans became the victims of forced migration. Local economies were shattered. The national economy was devastated.

Beyond these cyclical and long-term effects, the human toll was enormous. Over 60,000 combatants gave their lives for Eritrean independence. An estimated 40,000 civilians were killed as a direct consequence of the conflict. Eritrea today is home to 90,000 orphans or unaccompanied children and 10,000 men and women combatants who are severely disabled. These are but the most obvious indicators of the destruction caused by three decades of conflict.

The cycle of famine that emerged by the early 1980s had a serious impact. By liberation, 75 percent of Eritrea's people were dependent on food aid. Both the causes of and responses to famine in Eritrea unfolded in the context of war and political conflict.

By the early 1980s, the ability of Eritrea's rural majority to sustain itself had eroded substantially. Ground offensives by the Ethiopian army pushed people off their land. The disruption of rural-urban commerce reduced the ability of small-scale producers, commercial producers and merchants alike to engage in local trade. The livestock sector, on which most Eritreans depend, was similarly disrupted. The cost of basic commodities increased during the war. In the face of an ever-declining ability to generate funds, few Eritreans could purchase or replace the items needed for production. As the Ethiopian Air Force intensified its campaign of aerial bombardment, both crop land and rural markets came under attack. In many areas of Eritrea, farmers were forced to cultivate their fields at night.

Against this backdrop, Eritrea and the region suffered four successive droughts. With war increasing the economic vulnerability of Eritrea's agricultural sector, more farmers were forced into dependence with each passing year. By 1984, most of Eritrea's farmers could not survive without outside assistance.

An important goal of the armed struggle was meeting the basic needs of the population and supporting the process of economic development. To this end, the Eritrean Relief Association (ERA) was formed in 1975. Sectoral departments of the EPLF developed and carried out a range of development programs throughout the period of conflict.

Assistance came, in significant measure, from the Eritrean diaspora, which generously contributed to the efforts of Eritreans remaining in Eritrea. Non- governmental organizations (NGOs) also provided external assistance, helping ERA and the EPLF departments through cross-border operations from Sudan.

The 1984-85 famine made world headlines and generated a massive outpouring of support and assistance from multilateral institutions, governments, private aid agencies and individuals. The famine in Eritrea, however, was obscured in a shroud of silence created by the former Ethiopian government and continued unchallenged by the international community.

In Addis Ababa, the regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam declared that it had the means to reach all civilians affected by famine, including those in Eritrea. This was far from true. By the mid-1980s, most of Eritrea's rural dwellers resided in areas administered by the EPLF. Following a policy adopted years earlier, the Ethiopian government refused to allow relief or other assistance to flow to these areas. These people were entirely dependent upon the EPLF and ERA for assistance.

Repeated appeals to the international community were made well ahead of the famine's peak in 1984. International NGOs responded favorably and took initiatives to meet the needs of civilians living "behind the lines." However, the United Nations failed to provide any assistance on the grounds that its mandate required it to work only with official governments. Similarly, many bi- lateral government agencies opted to channel all their assistance to civilians living in government-held areas. Their position was based on the misguided assumption that the West could seduce Mengistu Haile Mariam away from the Soviet Union with humanitarian aid.

By the close of 1984, ERA had received less than 4 percent of what was required for civilians living in EPLF-administered areas of Eritrea. While aid levels did increase, the international NGOs providing the most assistance were unable to mobilize the resources required.

Bilateral aid agencies began providing indirect assistance late in the 1980s. How-ever, they and the UN steadfastly refused to officially recognize or respond to the needs of Eritrean men, women and children who faced starvation in the midst of a war that the Ethiopian government declared nonexistent. This was even more disturbing given the efficient and committed efforts Eritreans made to support their own people. Truck convoys carried food to villages where community members managed distribution. Much of the relief operation was conducted at night to avoid the risk of aerial attack by the Ethiopian Air Force.

Famine recurred in 1987 and 1989. The consequences were dire. Thousands of people perished and over 200,000 were forced into temporary exile in neighboring Sudan. Thousands more were displaced within Eritrea, and were thus unable to cultivate their land. When food did not arrive in sufficient quantities, farmers sold their livestock and tools. Few could generate the income necessary to reinvest in these productive assets.

Gradually the international community began to channel more assistance to war-torn areas of Eritrea. Nonetheless, the historic fact remains that the cycle of famine begun in 1984-85 was due to the shortfall in assistance.

The politics of famine were made explicit when the EPLF liberated the port of Massawa in February 1990. Massawa then served as the primary off-loading point for relief assistance provided to both Eritrea and Ethiopia. In keeping with its commitment to humanitarian principles, the EPLF offered to keep the port open for shipments to both countries. Continued aerial bombardment by the Ethiopian Air Force, coupled with Ethiopian unwillingness to concede loss of the port, meant that the port could not open until January 1991.

Human displacement emerged as a consequence of conflict. Early as 1967, massacres of civilians by Ethiopian government troops triggered the first major exodus of Eritreans to Sudan. The causes of flight from Eritrea from that point forward were military and political.

Entire villages were destroyed. Young men and women were shot on the streets of Eritrea's cities. Forceful discrimination against Eritreans led to the widespread development of a well-founded fear of persecution. Both the urban and rural sectors were affected.

Although the violence and destruction that characterized the war in Eritrea went little--noticed by the outside world, the thirty years before liberation were marked by consistent and extensive violations of human rights. Starving citizens were denied their fundamental right to food. Throughout the war, successive Ethiopian governments pursued a policy designed to terrorize civilians and undermine their support for self-determination. While this policy was never effective and instead strengthened the Eritrean people's resolve, the physical and psychological consequences were extreme.

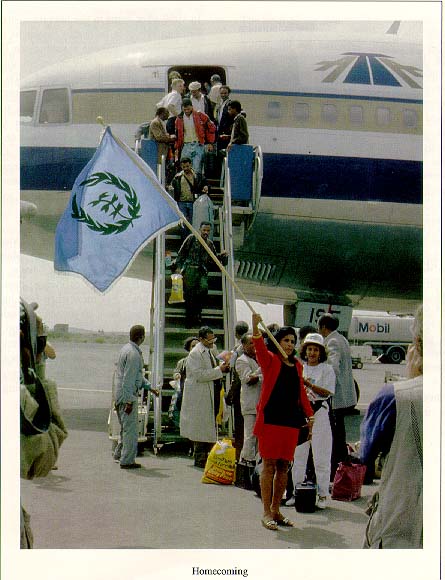

Over one-half million Eritreans lived as refugees in neighboring Sudan. Thousands of others sought refuge elsewhere in the Horn of Africa, in the Middle East, or in Europe and North America. During the thirty years of war, close to one-third of Eritrea's people were forced to leave their country because of successive Ethiopian regimes' military and political policies.

In the early days of the struggle, the Haile Selassie regime responded to ELF actions by burning villages and often slaughtering village residents. For example, in February 1967, 300 civilians were shot to death in Adi Ibrahim in the Barka region. In 1970, 750 men and women were either shot or stabbed to death in Ona, outside Keren. These actions triggered the first waves of Eritrean refugees to Sudan.

The Mengistu regime followed a similar course. In January 1975, 100 people were strangled with wire in Asmara. Fifty Eritrean political prisoners were executed in Asmara on 30 April 1988. In a village called She'eb, 400 civilians were either shot or run over by tanks and killed on a May afternoon in 1988. In June 1990, 17 young people returning to their homes in Asmara were shot. Another 30 youngsters shot and killed in a separate incident the same day.

Massive bombing killed thousands of people and destroyed the homes and schools of Eritrea's citizens. Both napalm and cluster bombs were used. The Ethiopian army regularly deployed MiG-24 helicopter gunships to attack crowded markets on weekly market days.

Significant damage was done to property, which was either destroyed or confiscated. In 1987-88 alone, for example, the Ethiopian army killed or confiscated 2,761 cattle, almost 90,000 goats and sheep and 7,000 horses and donkeys. During the same period, more than 10,000 homes and eight churches were destroyed. Twenty-two thousand hectares of agricultural land were burned or overrun and 347 shops were destroyed. Over 100,000 quintals of grain were taken or burned, and 50,000 grams of gold jewelry were seized.

The gradual erosion of local economies paralleled the destruction of the Eritrean national economy. Throughout Eritrea transportation infrastructure was so severely damaged or poorly maintained that both internal markets as well as export production were sharply constrained. Heavy military equipment damaged roads. The Ethiopian army used the railway tracks to fortify their trenches. The port of Massawa was extensively damaged during the last years of the war.

Industrial production declined during the war. Acute shortages of water and electricity contributed to its further collapse. Production fell to less than 30 percent of capacity and many workers suffered the effects of unemployment.

Educational facilities were closed down and turned into barracks. Health care facilities were turned over to the military. Other social services ceased.

In Eritrea today, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is only US $70- 150, compared to US $300 for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole. Life expectancy is only 46 years and the infant mortality rate is 135 per 1000 live births. Health facilities are available for only a minority of the population.

After Eritrea's liberation, the PGE proposed a two-year interim period during which preparations would be made for an internationally-supervised referendum on independence in Eritrea. With the change of government in Addis Ababa, for the first time an Ethiopian regime agreed to settle the conflict by peaceful means. Ethiopia endorsed the right of the Eritrean people to self-determination and voiced its support of the referendum.

During the two-year period following liberation, the PGE governed Eritrea. In a proclamation dated 22 May 1992, the PGE defined the provisional government structure to include legislative, executive and judicial bodies.

During this interim period, the EPLF Central Committee served as the legislative branch of government. It issued proclamations, formulated and implemented domestic and foreign policies, and approved the national budget. A 28-member Advisory Council headed by the Secretary General of the PGE formed the executive branch of government. The Advisory Council included the governors of Eritrea's ten provinces and the secretaries of key departments. The judiciary branch of government functioned independently of the executive and legislative branches.

From its inception, the PGE followed a policy of decentralization geared toward fostering balanced development, encouraging local initiative, and redressing past imbalances. Decentralization is seen as a crucial pillar of the democratization process. To this end, the PGE issued a proclamation defining the powers and responsibilities of local government. The system of administration extends from the provincial to the village level and ensures the full participation of the people in national as well as local affairs. Village and regional elections were conducted throughout the interim period.

Ten local governments -- Asmara, Akele Guzai, Barka, Denkalia, Gash-Setit, Hamasien, Sahel, Semhar, Senhit, and Seraye --were set up. Each comprises executive and legislative branches as well as an independent judiciary. These three components of local government are reproduced at the provincial, district and village levels, with the sub-provincial level comprising only the executive and judiciary branches.

At each level, members of the legislative branch are democratically elected. Population size and other factors particular to the region in question determine the number of seats apportioned at the provincial council level. Efforts are made to ensure adequate representation of ethnic language groups and the full participation of women. While elections are based on universal suffrage without gender distinction, several seats are reserved for women to ensure that they are adequately represented.

The central government appointed provincial and sub-provincial governors. The provincial governors served as members of the Advisory Council of the PGE. District and village level executive members are elected from the local assembly or appointed by the provincial governor. Regional governments enjoy broad autonomy and are responsible for many development programs and the delivery of social services. These regionally--based structures also levy taxes and allocate budgetary appropriations.

Besides defining and putting in place decentralized structures to foster participatory governance, the PGE continued initiatives to put in motion the process of economic and political transformation in Eritrea. In sharp contrast to other developing countries that must maintain and reform an existing government, Eritreans, as citizens of a newly independent state, are challenged to create new and appropriate mechanisms entirely from scratch.

The EPLF and the PGE have acted on their commitment to democratization. This pledge is not born of a desire to respond to current international trends. It is part of a history of democratic struggle that began in the 1940s and continued through the period of armed struggle. Most important, democracy fulfills the aspirations of the Eritrean people, expressed through their long struggle for independence and clear desire for peace, stability, equality and prosperity.

Elections, for example, are not new to the many Eritreans who lived in EPLF- administered areas during the war. There, the principles of religious freedom, women's equality and human rights were actively practiced. The elected committees and councils operating at the village level throughout Eritrea today form the basis for the growth of democracy. Through these institutions the people of Eritrea are addressing the issues they deem important and which affect them on a day-to-day basis.

While democracy has strong roots in Eritrea, its thorough application cannot be determined by a formula or timetables. Given the unmatched importance of democratic structures and policies in Eritrea's future, flexibility and thoroughness are critical. Emphasis must be given to building and expanding democracy from the bottom up. It cannot be imposed from the top by creating formal national structures without a base in society. A constitution and the framework for pluralism must emerge from a broad consensus. They must be based not only on legal expertise but also on the needs and views of Eritreans to whom the political system must be accountable.

During the interim period, the PGE put into practice its commitment to democracy. It developed a decentralized system of government and expanded the creation, through elections, of the local administrative structures built during the war.

The PGE also developed and enacted Civil and Criminal Codes. They include the right of habeas corpus and a 48-hour limit on detention without charge. In 1991, the PGE abolished the censorship boards of the former Ethiopian regime. A broad range of rights for women, including guarantees for equal educational opportunity, equal pay for equal work, and legal sanctions against domestic violence, were codified in 1991.

The referendum in itself was a profoundly democratic experience involving all citizens living in and outside the country. Over 98 percent of eligible voters participated. This process not only decided Eritrea's future. It served as a learning experience for the entire population.

Acting on the desires of its members and of the people of Eritrea, the PGE committed itself to facilitating the development of an Eritrean constitution and the emergence of a pluralistic system that encouraged both political parties and civic organizations. These initiatives will based on appropriate study, debate, and full consideration for the characteristics of Eritrean society.

The PGE took the position that Eritrean political parties should not be based on religion or ethnicity. The people of Eritrea are both Christians and Muslims. The country includes nine language groups, each with their own cultural characteristics and traditions. Government policies reflect this diversity within a framework of unity and commonalty of purpose.

With the end of the war came gradual recognition of the right to self- determination by the international community. The UN and OAU, joined by representatives of regional and international governments, actively participated in observing the Eritrean referendum. During the interim period, the governments of Djibouti, Egypt, Italy, Sudan, the United States, and Yemen established a formal diplomatic presence in Asmara. Others initiated relations with the PGE but opted to wait until after the referendum to establish a full diplomatic presence.

The UN's operational agencies opened offices in Asmara shortly after liberation. Several international non-governmental organizations, many of whom provided assistance to Eritrea during the war, also did so. New NGOs, the European Community, and the aid agencies of some donor governments followed. The PGE received its first World Bank mission in September of 1992 and successfully concluded negotiations for an emergency assistance package in early 1993.

The PGE has given great emphasis to establishing good relations in the region. It developed relations, based on the principles of mutual respect and non-interference, with all neighboring countries. Today Eritrea enjoys a warm and effective working relationship with the TGE. This is the basis for the development of peaceful and productive Eritrean-Ethiopian relations in the future. Relations have also been established with various governments in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Australia and Asia.

The PGE's decision to delay the referendum until two years after the liberation of Eritrea had its cost in financial terms. Eritrea's temporary status during the interim period meant that it could not function with the full benefits accorded a recognized independent state. Major packages of foreign assistance were prohibited or sharply limited until the post-referendum period. With the completion of the referendum process and the international community's declaration that it was free and fair, Eritrea's entry into the community of nations proceeded smoothly and quickly.

In the economic field, the PGE committed itself to developing a market-based economy. The economy should give the widest possible scope to private foreign and domestic investment while raising the population's standard of living. To this end, the PGE issued Investment and Labor Codes. It established an investment corporation and commissions to resolve land disputes and explore land policy.

The Investment Code issued in December 1991 aims to expand exports, encourage import substitution, increase employment and introduce new and appropriate technologies. Incentives include exemption from customs duties and taxes, exemption from income tax, preferential treatment in allocation of foreign exchange for imports, tax reductions, and liberal provisions for remittance of foreign exchange abroad.

At present, the government is managing several public enterprises nationalized by the former government of Ethiopia. It plans to privatize or close these in the near future.

The Labor Code stipulates, among other provisions, that workers have the right to form and join unions as well as the right to strike. Collective bargaining is also recognized.

Political democracy cannot be achieved without sustainable and equitable economic development. The PGE continued its considerable emphasis on the rehabilitation and reconstruction of Eritrea's war-ravaged economy. To this end, the it developed and begun negotiating funding for a national Recovery and Rehabilitation Programme (RRP) for Eritrea. The RRP is designed to jump-start the Eritrean economy, which ceased to function with any effectiveness by the end of the war. It addresses the immediate needs of infrastructural repair. The programme also aims to lay the basis for long-term economic growth and development.

In the programme, top priority is given to the productive sectors (agriculture and industry), essential infrastructure (energy, roads and ports) that sustain the productive sectors, and the strengthening of government institutions. Refugee repatriation and reintegration, and the demobilization of former combatants are components of the programme. The RRP's total budget is US $2 billion.

Despite the destruction wrought by the past, Eritrea has bright prospects for a stable and prosperous future. It has an enterprising population, a strategic location, and an efficient corruption-free government that can make maximum use of very limited resources. Many believe that Eritrea will be a success story, not only socially but also economically.

The primary challenges facing the people of Eritrea in the wake of the independence victory are rehabilitation and reconstruction. The Eritrean people must regain their economic independence and prosper. These challenges also provide the practical basis for democratic dialogue on the course of the country's future.

Infrastructural rehabilitation and expansion are prerequisites for economic recovery and growth in Eritrea. As such, the PGE emphasized this sector, a central component of which is national energy resources. Eritrea suffers from an acute shortage of available energy resources. The single main source, biomass (wood and charcoal), makes up 82 percent of total energy consumption. Oil and electricity comprise the balance. Consumption patterns reflect a structural imbalance. The house-hold sector consumes almost 80 percent of all energy. Industry uses 14 percent and transport 6 percent. Agriculture and other sectors consume only 2 percent of energy resources.

The Department of Energy was established in 1991. Its primary goals are the provision of adequate and inexpensive energy to all sectors of the economy; the development of a proper energy distribution system; the promotion of appropriate, cost-effective and environmentally sound energy usage; and the diversification of energy sources within Eritrea.

The Department of Energy established the Petroleum Corporation of Eritrea, with a main branch at the Asseb Refinery built by the Soviet Union in 1967. It also set up two new sections to explore alternative energy sources. The Hydrocarbon and Geothermal Energy Section studies and, as appropriate, exploits potential geothermal energy in the Danakil Depression between Irafale and Dallol. The Renewable Energy Section is developing a program to educate the Eritrean public about renewable energy and energy conservation.

Although once extensive, telecommunications facilities in Eritrea also fell into decline during the war. The Telecommunications Authority of Eritrea was established in May 1991 with automatic exchange service concentrated in three towns -- Asmara, Asseb and Massawa. International traffic is currently routed via a new INTELSAT standard A earth station was commissioned in 1993. It works with the Atlantic Ocean Region Satellite. The Telecommunications Authority plans to expand services.

Eritrea issued its first official postage stamps to coincide with the referendum. While international postal service has been reestablished with some countries, both international and domestic postal facilities function at levels well below need.

The development of transportation infrastructure has been given importance by the PGE. Both internal and export-based marketing systems and the delivery of basic social services require this infrastructure. The PGE undertook programs to repair or maintain the existing road network immediately following the liberation of Eritrea. In the coming years increased emphasis will be given to expanding and improving Eritrea's road networks.

The airport at Asmara was given over to military services during the war. The PGE repaired it to allow for normal operation. The Eritrean Civil Aviation Authority has taken control of Eritrean airspace. It reached an agreement with its Ethiopian counterpart for the division of airspace and air traffic service coordination. Cargo stores have been repaired and an electric power line has been installed at Asseb airport. Air transport controllers and other technical staff are also being trained.

Eritrea has vast needs in the area of water supply. The Department of Water Resources is developing and implementing national water policy and water development programs. Due to war and neglect by previous regimes, there are no recent studies of national water potential. Eritrea's water table has dropped with the recurrence of drought. In many rural areas, wells have run dry or dropped to low levels of output. Existing urban water supply systems date from Italian rule and subsequent regimes did little to maintain them. Overall leakage is about 35% and the systems are inadequate in the face of increasing demand. Rural and urban water supply systems will come under further stress as refugees return to the country in large numbers.

In the face of these adverse conditions, the Water Resources Department carried out a crash program to rehabilitate water resources and repair or replace pipes and fittings. Studies on water resources and potential are also underway. The department is training and upgrading staff to achieve its goal of providing all Eritreans with clean water supplies.

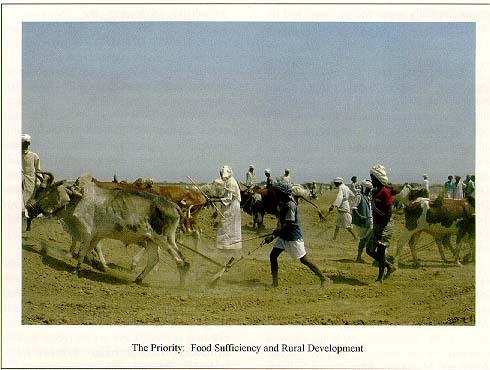

Because of the urgent need for increased production, the PGE gives priority to the agricultural and industrial sectors along with the rehabilitation of infrastructure. Agriculture is the most important sector of the Eritrean economy, accounting for approximately 50 percent of the GDP, 70 percent of exports and the livelihood of 80 percent of the population. Production is based primarily on small-scale peasant cultivators and on pastoralists.

As a result of the war and recurrent drought, export crop production in Eritrea is now virtually nil. Food production has dropped by 40-50 percent and the livestock sector has been reduced by two-thirds. However, the potential for growth is significant. Out of a total land area of 12.4 million hectares, over 25 percent is suitable for agriculture use but only 10 percent of this is currently under cultivation. An estimated 600,000 hectares can potentially be irrigated.

The Agriculture Department aims to improve the Eritrean people's stand of living by focusing on food security, employment generation, supply of raw materials to domestic industries, generation of foreign exchange earnings through direct or indirect exports, and environmental protection and restoration. In the food sector, agricultural output will be expanded to increase both consumption and purchasing power.

The department promotes productivity through provision of modern agricultural inputs and practices, expansion of high-potential areas, rehabilitation and expansion of existing commercial farms, and establishment of new agro-industrial estates.

In addition, it is working to increase livestock and poultry production by restocking and provision of veterinary services. In the environmental sector, emphasis is given to massive terracing, afforestation and the introduction of water harvesting techniques.