webmaster

© Copyright DEHAI-Eritrea OnLine, 1993-2010

All rights reserved

From: Tsegai Emmanuel (emmanuelt40@gmail.com)

Date: Mon Sep 13 2010 - 22:23:10 EDT

A Possible Kenyan Alternative for Southern Sudanese Oil

September 14, 2010 | 0020 GMT

Summary

Kenya is set to take bids for construction of a new deepwater port in Lamu,

and it has simultaneously raised the possibility of a pipeline to this port

from Southern Sudanís lucrative oilfields. In addition to the economic

benefits for Kenya, Southern Sudan could see the pipeline as economic

freedom from the north, especially in the context of an upcoming referendum

for Southern Sudanese independence.

Analysis

The Kenyan Ministry of Transport announced Sept. 13 that international

construction companies interested in participating in the development of a

new deepwater port in the northeastern town of Lamu have until Oct. 15 to

submit a bid. Nairobiís long-term vision is to combine the envisaged Lamu

port with a new transport network that will reach the capitals of Ethiopia

and the currently semi-autonomous region of Southern Sudan, thereby

integrating these neighboring economies into Kenyaís trade sector.

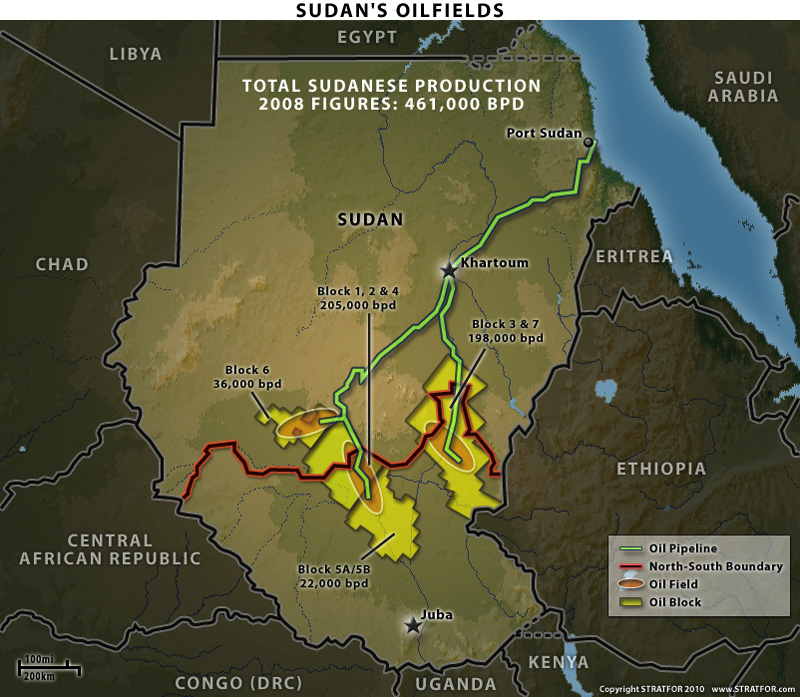

<http://web.stratfor.com/images/africa/map/sudan_oilfields_800.jpg?fn=1617122923>

The real geopolitical significance of the Lamu Port-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia

Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) project, however, lies in the effect it could

have upon Southern Sudanís potential to exist as a viable independent state.

Southern Sudan, which is responsible for more than 80 percent of Sudanís

estimated 480,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil production, is

scheduled to hold a referendum in January 2011 on whether to stay in union

with the north. If the government in Khartoum allows the referendum to

happen, it is widely expected that voters will opt for Southern Sudanese

independence. This will not lead to the creation of a viable Southern

Sudanese state overnight, however, because the south cannot simply begin

making money from its oil industry the day after becoming independent. The

only export route by which the oil can be shipped goes through the north,

exiting at the Red Sea town of Port Sudan, thereby giving Khartoum the

ability to choke off Southern Sudanís crude exports at any time.

The fundamental question that has always plagued advocates of Southern

Sudanese independence, then, has been how the state could ever function as a

viable entity of its own. As it stands, the Southern Sudanese government in

Juba gets 98 percent of its revenue from an oil-revenue-sharing agreement

formed in 2005, when the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA)

ended the second Sudanese civil war. The CPA affords Juba just under half of

the proceeds from oil pumped out of its territory, but it is set to expire

in July 2011, six months after the referendum on

independence<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20091229_sudan_agreement_last?fn=1717122985>.

Should the south vote for separation, Khartoum will not sit back and allow

Juba to simply take all the oil money with it. A vote for secession could

therefore either lead to

war<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20100105_sudan_khartoum_threatens_peace?fn=1917122912>or

to a revenue-sharing arrangement very similar to the one that exists

under the CPA. An independent Juba would prefer the latter, of course, but

its long-term interests would be best served with a third option: a pipeline

from Southern Sudan to Kenya.

The LAPSSET project creates this possibility. It envisions the construction

of a deepwater port in Manda Bay, just west of Pate Island in the Lamu

Archipelago, which will then be connected to a road and rail network that,

when completed, will reach Juba and the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa. It

also includes plans for a potential accompanying pipeline, with some plans

indicating that a crude oil refinery will also be built in the vicinity. The

Kenyan governmentís Sept. 13 announcement deals with only the first phase of

the project, however, which focuses specifically on developing the port; the

rest of the project is still years from being launched. While the total

estimated cost of this first phase is not yet known ó a Japanese consulting

firm is currently finishing a feasibility study it was contracted to carry

out last April ó rough estimates for the overall LAPSSET project peg it at

around $16 billion with a window of 3-5 years before completion.

This is an enormous sum, and Kenya is clearly looking for help from foreign

investors in financing the project. So far, the two countries that have

shown the most interest have been China and Japan (though a South Korean

company has expressed interest as well). These parties are interested in the

pipeline especially. Earlier this year, Toyota Tsusho Corp.

(TTC)<http://www.stratfor.com/sitrep/20100304_brief_kenyan_discussion_pipeline_lamu?fn=1417122956>,

the trading affiliate of Toyota Motor Corp., proposed building a $1.5

billion, 450,000 bpd pipeline to transport crude oil from Southern Sudan to

a planned port on Lamu Island. TTC agreed to help construct a port, an

export terminal equipped with a storage tank and an oil jetty, and expressed

interest in possible participation in the rail project as well. TTC also

said that a joint venture would be possible, mentioning the possibility of

Chinese involvement. The Chinese, meanwhile, have also expressed interest in

helping Nairobi finance the project, after Chinese President Hu Jintao

reportedly offered his Kenyan counterpart, Mwai Kibaki, a 1.2 trillion

shilling grant (just under $15 billion) in May.

China is believed to import roughly 64 percent of Sudanís crude (neither

Sudanese nor Chinese production figures, which contradict one another, are

considered particularly reliable). State-owned China National Petroleum

Corporation is the largest stakeholder in Sudanís two biggest oil-producing

consortiums, and the Chinese built the pipeline connecting Southern Sudanese

oil fields to Port Sudan ó ironically, the same pipeline Juba is hoping to

get around by linking up with Lamu. Japan, meanwhile, is not involved

directly in the Sudanese oil industry like China but is nonetheless a large

consumer of Sudanese crude. Both countries have an interest in ensuring the

unimpeded flow of oil from the country, and, like many other countries,

appear to be hedging their Sudanese policies to account for the possibility

that they may need good relations with the south, in preparation for any

scenarios that may follow the referendum.

Though Kenya, as a coastal trade center, is already one of East Africaís

leading economies, it wants to improve its position through the development

of a second deepwater port. Kenyaís Mombasa port is the leading deepwater

port in East Africa<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/kenya_protests_president_and_supply_chain?fn=9117122987>,

but it suffers from chronic delays due to overcrowding, it is also shallower

than Lamu and it is unable to accommodate post-Panamax vessels (which Lamu

would be able to handle). Having only one major port at Mombasa, which is

320 km (200 miles) by road from Lamu, also prevents Kenya from being able to

effectively integrate the economies of the region that abut northern Kenya,

as there is no effective road or rail network that can transport goods

between these regions. (Ethiopia, for example, is largely reliant on the

port of Djibouti for its outlet to the world, and Addis Ababa also wants to

diversify.) A deepwater port at Lamu would also be beneficial for the

trafficking of military supplies from the United States, which holds regular

military exercises with the Kenyans there. It is strategically located near

Somalia<http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20100121_somali_al_shabaab_threatens_kenya?fn=3117122936>but

safe from the dangers of piracy.

- Despite all of the benefits the LAPSSET project promises to bring, its

completion may also create a separate problem for Khartoum. So long as

Southern Sudan depends on the north to be able to export its crude deposits,

it holds significant leverage over Juba. The long-term prospect of an

alternative pipeline weakens the Sudanese governmentís hand. Then again,

Juba, due to its geography, can never rest easy when it comes to Khartoum.

Even if a new pipeline were to be built, it would have to maintain good

relations with the north to prevent Khartoum from fomenting instability

within its territory.

----[This List to be used for Eritrea Related News Only]----