THE capital of Niger is not known as a hotspot for planespotters. But passengers waiting to take off at Niamey’s airport are sometimes in for a treat: the sight of an American Predator drone elegantly gliding down ahead of them on its only runway. If they take off and look out of the window, they will see a generously sized base with new-looking hangars and several American transport aircraft.

It is not the only sign of America’s presence in Niamey. The embassy is unusually large; the city’s best restaurants buzz with American accents. And now, at Agadez, an ancient desert city in the north of the country, that is a transit point on the route to Europe, mixed in with the smugglers and migrants are contractors from Europe and South Africa, quietly building another base for drones. Niger, a desperately poor country on the edge of the Sahara—in the semi-arid region known as the Sahel—with a population of some 20m, has become a key location for America’s expanding security presence in West Africa. It is a sign of growing worries about jihadism in the region and of America’s stepped-up efforts to contain it. But the local effects of importing Western might are not always benign.

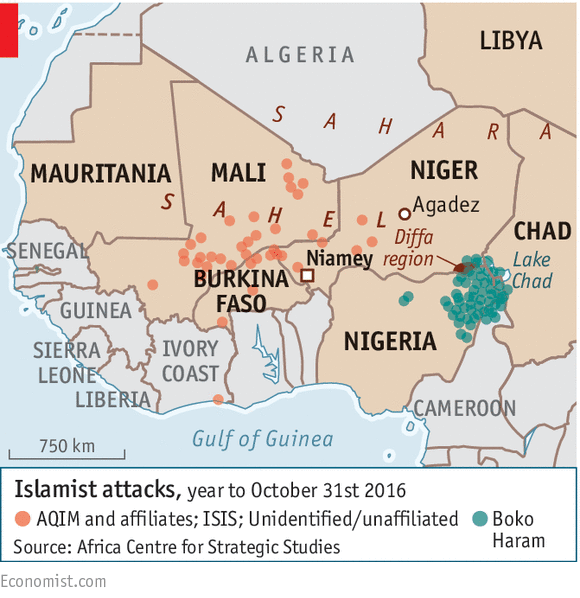

American involvement in the Sahel began in earnest in 2005 with the Trans Sahara Counter-Terrorism Initiative. In 2007 the Pentagon launched AFRICOM, its military command for Africa. Since then, the number of special forces operatives active in Africa has risen sharply; on average around 700 are deployed there. In the western Sahel region drones also fly from a base in Chad, while small surveillance planes operated by contractors have flown from Burkina Faso and Mauritania. America is not the only country with operations in Niger; France, the former colonial power, also has a base there and Germany is building one too (which it says will be for logistics only).

The focus on Niger makes sense. The country is at the centre of several conflicts. In the north-west Mali’s Islamist insurgency has spilled over the border. On 14th October, an American aid worker was kidnapped; a week before that, 22 of Niger’s soldiers were killed in an attack on a refugee camp. In the south-east, near Lake Chad, over the past few months Boko Haram’s insurgency against the Nigerian government has pushed thousands of refugees into Niger’s Diffa region. And from the north and north-east, weapons and fighters from Libya threaten to destabilise a region already known for violent uprisings, particularly from the Toubou and Tuareg desert tribes.

The worry is that these conflicts will link together, or already have. “There is a big split in American policy on understanding it as a globally connected jihadi group or not,” says Brandon Kendhammer, of Ohio University. In the Pentagon it is generally thought that it is, he says; but officials in the State Department often think the opposite. While a part of Boko Haram has claimed allegiance to Islamic State, the evidence of practical links to the jihadists’ operations in Libya is thin: a few Nigerian fighters (not necessarily from Boko Haram) have turned up in Libya, but that is about it.

If there is more evidence to be collected, however, the Pentagon is sure to get it. The Predator and Reaper drones at the base in Niamey may look intimidating, but they are used for surveillance, not launching strikes. Though details about the new base at Agadez are scarce, it is thought that it will play a similar role. In recent years drones have replaced surveillance flights flown by civilian aircraft out of bases in places like Burkina Faso. But that they are not carrying missiles does not mean missiles are not being fired by others. And in 2013, for example, when France launched a military offensive to push back Islamist Tuareg fighters in Mali (some affiliated with al-Qaeda) they probably benefited from extensive American intelligence.

So what is the effect of all this security co-operation? It seems to be helping to contain violent Islamism. Niger, unlike Mali, has not fallen victim to a major insurgency in the north since the early 1990s. A short rebellion in the late 2000s was quickly put down. In the Lake Chad region, while Boko Haram have launched attacks on Niger’s army, they do not control territory in the way they do in neighbouring Nigeria (where co-operation with Western forces is far more fraught).

As a result, aid agencies are able to operate, which means that displaced people are not starving. In the Diffa region, the Red Cross distributes food and water to tens of thousands of refugees who have fled fighting from across the border in Nigeria and built shanty towns on the edges of the highway, guarded by soldiers in smart uniforms with American-style camouflage.

Yet there are reasons to worry about America’s presence, too. Though a staunch ally of the West, Niger’s president, Mahamadou Issoufou, is no exemplary democrat. He was re-elected in February, but only after the opposition boycotted the second round of the vote. His main opponent was locked up and then fled the country for exile abroad.

Ali Idrissa, a Nigerien journalist and political activist, says that Mr Issoufou has no legitimacy. “We have a super rich political class and a mass of people who have been abandoned.” He sees security co-operation with America as a way for the elite to hold on to power. “Why are the bases here? The sovereignty of Nigeriens has been sold. This is about the rich making more money and staying in power, not about protecting our territory.” On the streets of Agadez, it is not unusual to see “Dégage, la France!” (get out, France) scrawled on walls. Critics say the West is only interested in Niger’s uranium, whose proceeds accrue mainly to the well-connected.

Political resentment helps fuel the Islamists—who also thrive on anger at the way war is conducted (it is suggested that a ban on motorbikes in Diffa has helped Boko Haram recruit, for example). Much of Niger’s territory is hot, dusty and infertile. Conditions are worsening because of climate change. Almost a third of its imports are covered by aid. Security co-operation is one of the few things its government can offer. Against an Islamist insurgency across West Africa, it is a useful ally. But government repression also helps fuel insurgency. And as long as the money keeps flowing, it has little reason to change its ways.