Date: Sat, 14 May 2016 13:01:48 +0200

The Sykes-Picot deal is reviled across the Middle East as the epitome of imperial arrogance, but the alternatives are grim too

Sir Mark Sykes (L) and Francois Georges-Picot (Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons)

Saturday 14 May 2016 23:01 UTC

This is certainly true of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which celebrates its 100th birthday on Monday.

The secret deal to divide the Ottoman Empire’s vast land mass into British and French zones of influence precipitated the borders of Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and much else in the Middle East that exist – at least nominally – to the present day.

That order is now threatened like never before. Iraq is coming unstuck; the Kurds run their own affairs up north. Syria’s civil war is so brutal that it is hard to imagine a unified nation emerging from the ashes of its barrel-bombed cities.

The Islamic State (IS) group wilfully defies any frontier blocking its route to an Islamic caliphate. According to Tarek Osman, author of Islamism, we are only part-way through a revolution with no clear endgame.

“Sykes-Picot was a pillar of a system in the Middle East that we are watching fall apart today, as something new is being formed. Right now, we’re in a fluid, chaotic phase and a new system will not emerge for a number of years,” Osman told Middle East Eye.

“I don’t know what that system will be. It could have a sectarian element, it might have some old features from the past 90 years, and it may see new nations created. But the system of which Sykes-Picot was a part is crumbling.”

Agreement largely reviled

There are few fans of the Sykes-Picot deal in the Middle East nowadays. It is reviled as the epitome of colonial Europe greedily pursuing its own interests while trampling over local desires for self-rule.

That’s a fair cop. Both Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot – respectively the British and French diplomats who brokered the deal – were unabashed aristocrats who thought Arabs and their neighbours were better off under the yoke of Europeans.

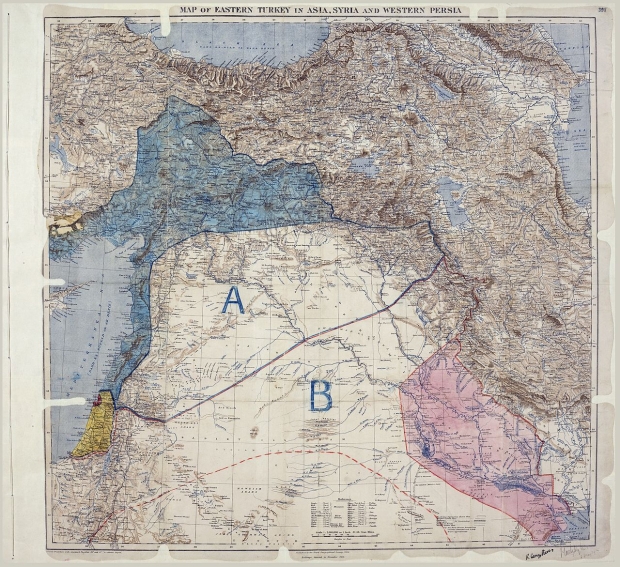

Indicative of imperial haughtiness, Sykes, speaking in No. 10 Downing Street in 1915, showed how he would “like to draw a line from the ‘E’ in Acre to the last ‘K’ in Kirkuk”, while sliding a finger across a map from the Mediterranean to northern Iraq.

Map of Sykes–Picot Agreement showing Eastern Turkey in Asia, Syria and Western Persia, and areas of control and influence agreed between the British and the French (Wikimedia Commons)

As the First World War raged, Sykes and Picot debated mostly-straight lines across the Middle East and in May 1916 inked a deal in which Iraq, Transjordan and Palestine went to Britain while the French got Syria and Lebanon.

To Arabs, it represents a broken oath. London had earlier promised Arab leaders that if they backed Britain and its allies by rebelling against the Ottoman foe, the fall of that empire would win them independence.

They only found out when Russia’s new Soviet rulers outed the British and French in 1917.

For Kani Xulam, director of the American Kurdish Information Network, such deal-making in far-flung capitals left the Kurdish region – which encompasses modern-day Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Iran and much else – “partitioned as if it were a cooked American thanksgiving turkey”.

“Eventually, the French and the Brits left the Middle East. But they left us to the tender mercies of folks like Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Syria’s Hafez al-Assad. I don’t need to repeat what they did to us,” Xulam told MEE.

“The demise of the Sykes-Picot agreement is, of course, good news for the Kurds. My only regret is that it received its first deadly blow from the Islamic State. I wish we had done that ourselves.”

The Sykes-Picot-era frontiers did not correspond to the sectarian, tribal or ethnic divisions on the ground, said Osman. But these differences were buried in the early 20th Century as Arabs struggled to eject the Europeans and build a pan-Arab identity.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Arab world’s strongmen – such as Hafez al-Assad, Saddam in the Levant and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in North Africa – suppressed these divisions, often with violence. They were vested in preserving their national borders.

The anti-autocrat Arab Spring uprisings re-opened ethnic splits – not least in Syria, where IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi rejected the map of the Middle East and sent Sunni Muslim soldiers to butcher Shia Muslims, Yezidis, Christians and others.

Addressing the world’s Muslims in July 2014, after IS had seized the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Mosul, al-Baghdadi said “this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy”.

Despite the desire of IS, other disaffected Sunnis, Kurds and other minorities, to re-define the region’s frontiers, they remain recognised in most Arab capitals, Iran, Turkey and by the UN and global powers.

'Imperialism 2.0'

Not only has the United States spent blood and treasure defending the borders of Iraq and Syria – Russia, Europeans and others have skin in the game. Despite talk of federalism, Kurdish autonomy and “Sunnistan,” the Sykes-Picot-era borders are the agreed ideal.

“With the rise of IS, some people say it’s time to redraw those borders. That’s essentially imperialism 2.0,” former Pentagon official Michael Rubin told MEE.

“Even if someone did it, would it resolve conflicts? The Middle East’s people don’t live in neat pockets, they’re spread out. New borders could not slice neatly between different groups. In the event of a re-draw, what would be the second- and third-order effects?”

Doubters warn that divorces are seldom amicable. The breakups of Sudan, Yugoslavia and India spawned huge migrations, cycles of ethnic violence and rival claims to resources and land, which in turn sparked whole new conflicts, some still unresolved years later.

And while the straight lines drawn by Sykes and Picot a century ago largely ignored ethnic realities, the states that emerged were not imaginary. Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Mt Lebanon all had a historic identity, even without agreed frontiers.

“It’s certainly in vogue to bash imperialism, colonialism, and the West’s legacy. But what is stylish is not necessarily right,” added Rubin, from the American Enterprise Institute, a think tank.

“Rather than lament Sykes-Picot, let’s recognise it for what it was: a mechanism born in imperial cynicism that nonetheless provided opportunities, often missed, for freedom and national aspiration.”