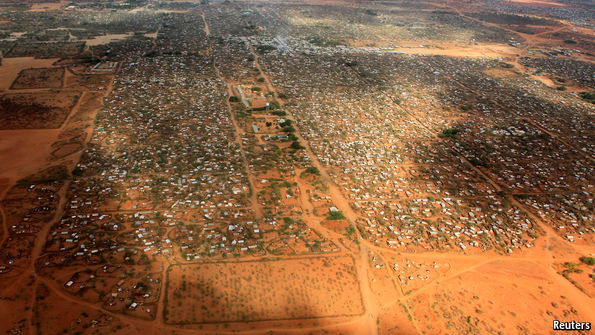

THE world’s largest refugee camp looks permanent. The first tents were pitched in the desert almost 25 years ago. Dadaab now sprawls over more than 50 square kilometres (20 square miles) on the arid Kenyan-Somali border. It is home to some 344,000 people, mostly Somalis who have fled their war, as well as shops, makeshift cinemas and a football league. The Kenyan government now wants to dismantle what is in effect a medium-sized city, along with Kakuma, a second smaller camp of 189,000 refugees close to South Sudan and Uganda. Neither task will be easy; either would provoke outrage.

The country’s interior ministry announced on May 6th that it wanted to close the two camps as quickly as possible, citing risks to national security. A similar pledge was made last year after 147 students at Garissa University were killed by attackers from a Somali terrorist group, al-Shabaab, (who some security officials say had links with Dadaab). On that occasion, an international outcry, culminating in a visit from John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, forced the government to back down. This time it seems more serious. It has repeated its declaration several times; and now, ominously, Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) has also been shut down.

“We can’t do anything right now because we don’t exist,” says one aid worker. Some 70-100 asylum seekers arrive from South Sudan every day, but they cannot be registered and moved into Kakuma’s main camp, according to Lennart Hernander of the Lutheran World Federation, which manages the camp’s overflowing reception centre. The DRA is (or was) also responsible for issuing passes for medical emergencies that cannot be treated in camp hospitals; charity workers fear death rates will rise as a result.

Aid agencies in Kenya and beyond have struggled to respond to the latest announcement. As The Economist went to press the UNHCR still had not been able to meet the government to decipher its motives or plans. In an article published on May 9th the interior ministry’s top civil servant, Karanja Kibicho, said that terrorist attacks, including one on the Westgate Mall in 2013, had been “planned and executed from Dadaab”. Others, though, put more of the blame on endemic problems within the Kenyan security services. Although a settlement that size has almost certainly been infiltrated by al-Shabaab to some extent, “those attacks couldn’t have happened without the same kind of vulnerabilities you find across Kenya,” says Cedric Barnes of the International Crisis Group. Kenya’s security has been improving, thanks in part to increased intelligence co-operation with Western countries.

Money is probably the real reason for the sudden announcement. Mr Kibicho pointedly mentioned in his article that donor funds are being switched from Kenya to deal with the influx of migrants to Europe. Having seen Turkey secure promises of €6 billion of aid in return for taking migrants back from Greece, Kenya doubtless wants more from the West.

AMISOM, the African Union force in Somalia, to which Kenya contributes more than 3,500 troops, needs a new UN mandate at the end of May. Moving half a million people out of Kenya is impossible, at least without immense cruelty. So the chances are that the threat of closure is a desperate appeal for more funds. But whether any will be forthcoming is still an open question.