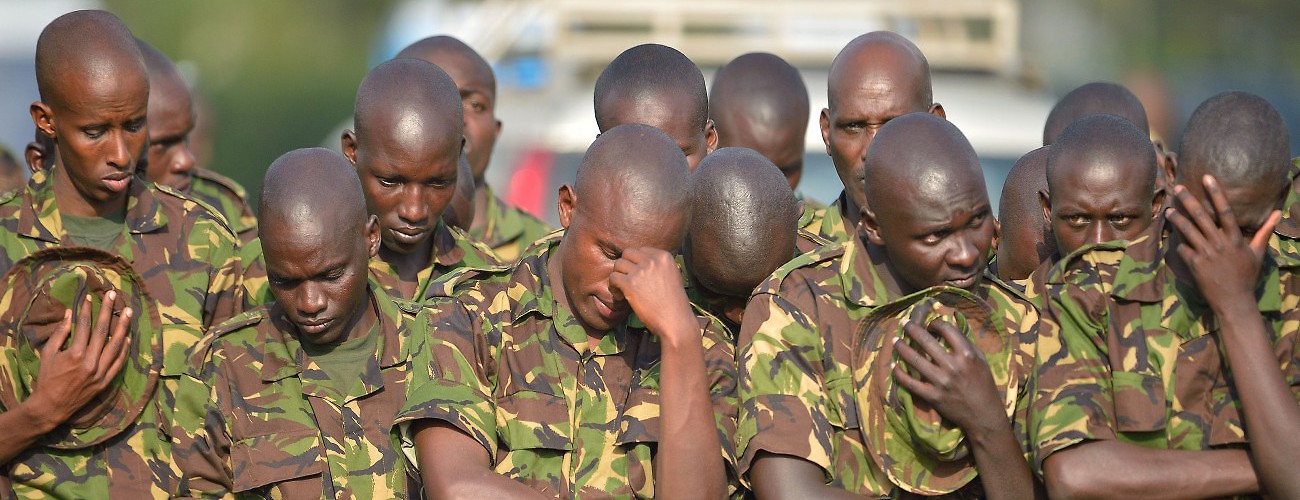

Kenya Defence Forces soldiers bow their heads during a memorial service for slain soldiers killed in southwest Somalia's el-Adde region by al-Qaeda linked Somali based Islamists, al-Shabaab. Nairobi, Kenya, January 27, 2016. (Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images)

Last week, the Somali militant group al-Shabaab issued a video vowing more devastating attacks on Kenyan soil. On Monday, a leaked Kenya Airports Authority (KAA) internal memo revealed that an al-Shabaab suicide assault team may attempt to target main Nairobi and Mombasa airports, putting Kenya on high alert. The group’s escalating propaganda efforts, coupled with a recent uptick in activity beyond the Somali western border, bolsters the credibility of the threat. But what is driving al-Shabaab’s escalation?

The al-Shabaab video came nearly a month after an assault by the group in El-Adde on a Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) base that killed over 100 Kenyan soldiers serving under the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), a clear sign of the group’s renewed focus on Kenyan targets. Responsibility for the January 15th attack was claimed by the Saleh Nabhan Brigade, so named for the martyred al-Qaeda leader; this brigade was also responsible for the July 2010 triple-suicide bombings in Kampala, and the December 2014 killing of 36 quarry workers in Kenya’s Mandera County.

Kenya has been under the threat from al-Shabaab since the beginning of its counterinsurgency campaign in Somalia on October 16, 2011. The military campaign, Operation Linda Nchi, was immediately declared an invasion by the Somali extremists who promised a painful response. Indeed, on September 21, 2013, al-Shabaab staged an assault on the Westgate mall in Nairobi, which resulted in at least 67 deaths. Two years later, Kenyan citizens were struck again after al-Shabaab militants killed 148 people in attack on Garissa University College on April 2, 2015. Since then, the Somali-based extremists have carried out a series of low-profile attacks, forcing Kenya into battle on its own soil.

In response, the Kenyan government initiated a series of steps to increase security. It has already been engaged in intelligence sharing with regional and international forces also battling al-Shabaab, which has been significantly strengthened over the past years. Military efforts aimed at eradicating al-Shabaab terror infrastructures—including against the group’s hideouts in the notorious Boni Forest on the border between Kenya’s Lamu County and Somalia—were launched in the second half of 2015. New technologies have also been employed, such as the CCTV system installed in Nairobi and Mombasa. The government has also purchased US-made Boeing Insitu ScanEagle drones for $9.86 million (KSh1 billion) in order to improve its surveillance capabilities, according to a leaked report.

While one measure shows the number of al-Shabaab attacks in Kenya decreased in 2015, there are growing indications of a resurgence in the group’s activity inside Kenya. Last October, Kenyan police issued a warning over al-Shabaab’s regrouping and intentions to taking advantage of the seasonal rainfall in order to stage cross-border incursions into Kenya. This, indeed, has been followed by a series of small-scale attacks and continued attempts to build up funding, recruiting, and training networks throughout the country. The country’s eastern counties bordering Somalia, especially Mandera, Wajir and Lamu counties, remain focal points for the Islamist activity. Just a week ago, Kenyan authorities placed US$780,000 (KSh8 million) on the heads of four notorious al-Shabaab operatives believed to be coordinating al-Shabaab operations in Mandera and Wajir counties. Records of arrests of militants on suspicion of recruiting and financing activities show they have been there since the beginning of 2015, but they also show the group has expanded into southern and central regions, including into Mombasa and Nairobi.

Further, al-Shabaab has capitalized on the media attention from the El-Adde attack and stepped up its anti-Kenya propaganda efforts. Besides the above-mentioned video, the group made public a video showing two ambushes of Kenyan security forces in eastern Lamu County. Public threats to target Kenya have become a common feature of the extremists’ media campaign. In tandem, while addressing security concerns, a Kenyan security official was quoted as confirming that al-Shabaab threat in Kenya is “still alive,” while pointing to the Islamists’ intent to execute more high-profile attacks against country’s security installations and soft targets, especially in northern counties bordering Somalia, as well as in coastal areas and major urban centers.

This escalation is being driven by a number of factors. First, under pressure from the ongoing AMISOM military campaign, al-Shabaab is seeking a boost in recruitment to continue its insurgency in Somalia. The group has previously demonstrated the ability to recruit nationals from other African countries to its ranks. But it is losing foreign fighters, including in East Africa, to the so-called Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh). Al-Shabaab reaffirmed its loyalty to al-Qaeda in July 2015, though many East Africans are drawn to the Levant-based extremists. Therefore, by rebranding itself as a leading regional Islamist force, al-Shabaab may hope to stop the East African flows and redirect them back to Somalia, and high-casualty attacks may be seen as vital to achieve this.

Besides the well-known ISIS, whose core theater of operations is over a thousand miles from Somalia, recent divisions within al-Shabaab have increased the number of actors in the region and may also lead to an intensification of attacks in Kenya. Al-Shabaab has recently witnessed several defections by ISIS supportive elements, a development which has created unwelcome competition over prestige and resources in its previously uncontested home region. Among those defectors is Abdurahman Mohamed Kuno, a former al-Shabaab top commander of Kenyan origin who masterminded the Garissa attack. After announcing the oath of allegiance to Daesh last November, Kuno’s faction has reportedly established a presence in areas along the border between Kenya and Somalia and is likely to contest al-Shabaab in the fight over the hearts and minds of potential sympathizers in Kenya. This is further supported by a statement from the Kenyan Inspector General of Police in December that Islamists operating in eastern Kenya split into two rival forces: the pro-ISIS faction, which is operating in Mandera County, and the al-Qaeda loyal al-Shabaab faction based in Boni Forest. Consequently, as both groups attempt to position themselves as the prominent Islamist group in East Africa, al-Shabaab may see a strategic advantage in operational gains that may help to eliminate the competition.

Second, while the group states its ultimate goal is to impose strict Sharia law and push the international coalition out of Somalia, probably the most powerful motivation for acts of violence in Kenya is the country’s approaching 2017 presidential elections. The group will likely increase its efforts to influence Kenyan public opinion in order to put pressure on decision makers as the election grows closer. In order to achieve this, it is increasingly likely that al-Shabaab will replicate the group’s most prominent successes such as the Westgate and Garissa attacks. This may also explain the decrease in small-scale guerilla-style attacks, due to their relatively limited public effect.

Moreover, while there has been no progress in the ongoing military campaign in Somalia, the vulnerability of the shared border to incursions, weak law enforcement in Kenya’s outlying areas, and country’s frustrated Somali population, which remains a target for Islamists’ recruitment efforts, further facilitate the ability of al-Shabaab to export its insurgency across the border to Kenya. Many local Kenyan youths have also proved susceptible to Islamist radicalization, prompting multiple security warnings over continued attempts to join the group’s ranks.

It seems clear that al-Shabaab will strike again on Kenyan soil in the near future. Simultaneous attacks with the use of multiple suicide bombers or storming teams comprised of several armed assailants, or the combination of both, against high-profile targets is the most likely scenario for the next assault. Security has been beefed up in major cities and other country’s regions prone to extremist violence, and we can only hope this is enough to prevent or minimize the next attack.

Olga Bogorad is an independent security analyst who writes on Islamist groups and trafficking in Africa.