PITY the UN ambassador of a small African country each time a vote is called in the General Assembly. Many of the resolutions will be ones that their president and most of their compatriots neither know nor care about. Take Resolution 70/230, adopted just before Christmas and new year when the world’s mind is on how it will recover from one hangover while bracing for the next. The UN resolved, among other things, to hold a symposium on basic space technology in South Africa and a workshop on “human space technology” in Costa Rica. It passed easily.

But what of more contentious resolutions, such as one condemning North Korea for abuses of human rights? Deciding whether to vote yea or nay ought to be easy: North Korea has one of the worst records on earth. Yet 19 countries voted against the resolution, among them Zimbabwe, Burundi and Algeria. Another 48 abstained, among them Kenya, Mozambique and Ethiopia. One reason, perhaps, is that China (which dislikes criticism of its pals in Pyongyang) smiles on nations that agree with it.

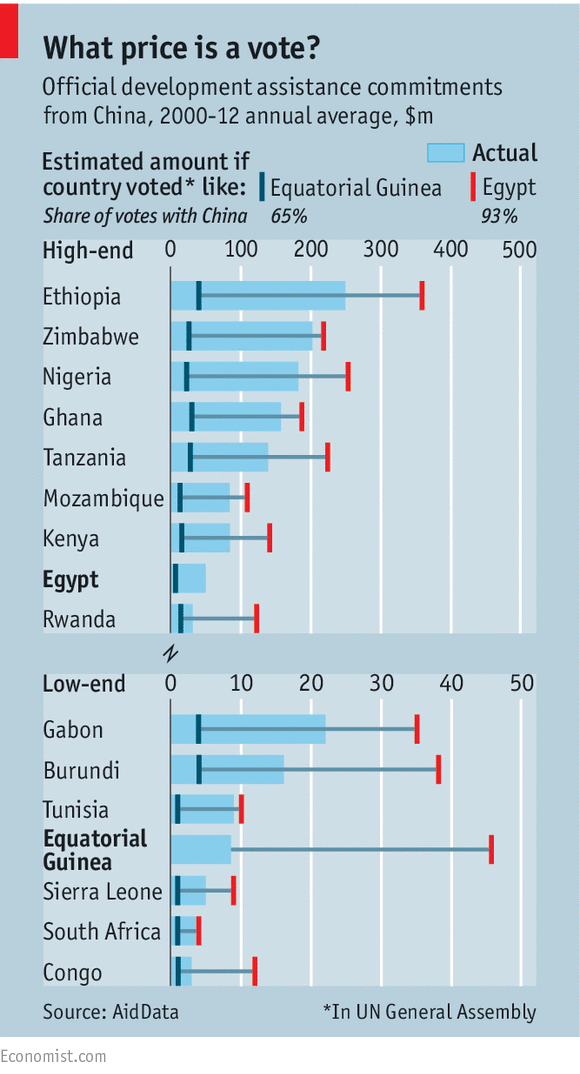

AidData, a project based at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, keeps a huge database on official aid flows. Its number-crunching shows how much China appears to reward African countries that vote with it. The relationship is not a simple one (see chart), according to Brad Parks, a director of the organisation. China gives proportionally more money to poorer countries, for instance. But by and large countries that support China do better. AidData reckons that if African countries voted with China an extra 10% of the time, they would get an 86% bump in official aid on average. If Rwanda, for instance, were to cast its ballot alongside China 93% of the time (instead of its current 67%), its aid from China could jump by 289%.

A purely self-interested foreign policy would need to take into account donors other than China, too. America’s Congress receives an annual report from the State Department showing which countries voted with Uncle Sam. Many academics claim to have found evidence that America, too, buys UN votes with aid. (If so, it is hardly consistent. Afghanistan routinely opposes American positions at the UN, yet still gets great dollops of cash.) Even so, cash-strapped African leaders should probably hire a data scientist or two to optimise the yield on their votes, or at the very least make sure their ambassadors turn up. Burundi, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo missed almost half of the votes that America considers key. Swaziland missed two-thirds of its opportunities to cosy up to America or China. Surely in the business of vote-buying the principle of “no vote, no pay” applies.