PEACE envoys in the Middle East have a thankless task. That is certainly true of Bernardino León, the Spanish diplomat who heads the UN’s mission to Libya. For months Mr León has been knocking heads together in the hope of bringing some semblance of unity to the country. But as The Economist went to press, the talks were faltering, days before the deadline of September 20th that Mr León has set.

Like previous rounds of jaw-jaw, the talks seek a power-sharing arrangement that would rid divided Libya of its parallel parliaments, governments and courts. Under the deal being proposed, the factions would form a government of national accord. The House of Representatives (HOR), the internationally recognised parliament in the eastern city of Tobruk, would have the primary legislative role. Much of the negotiation concerned the future role of members of the self-declared parliament still in Tripoli, known as the General National Council.

On September 15th the internationally recognised government in the east (based in the city of Beida rather than Tobruk) appeared to reject the deal after Mr León said amendments could be made to the draft, at the GNC’s request. A day later, the HOR turned up the pressure, saying it might stop exports to oil companies still dealing with the rival authorities in Tripoli.

There is little doubt that Libya needs a political agreement, and fast. The civil war that has raged since the downfall of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi has ruined the few institutions that existed. The country is thought to have used up a quarter of its foreign reserves last year. The next 18 months will see severe austerity measures. Jihadists of all stripes have fed off the chaos.

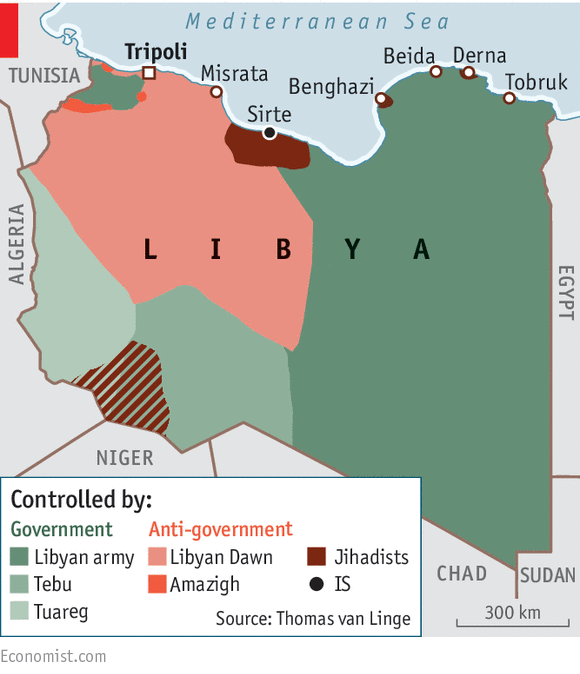

Most worrying is Libya’s Islamic State (IS) franchise. Since getting booted out of Derna, in the east, it has bedded down in Sirte, Qaddafi’s hometown. Two attacks in Tunisia, in the Bardo museum in Tunis and at a beach resort in Sousse, have been linked to men who trained in Libya.

Although some militias have declared a truce to focus on IS, most of them, including the force controlled by Khalifa al-Haftar, a former general who is affiliated with the Beida government, are more interested in fighting each other than defeating IS. That is why talk is growing in Western capitals of possible operations against IS in Libya. It is unclear whether this would be an extension of the coalition against IS which is currently only operating in Syria and Iraq, or a new grouping. Egypt, which has seen several of its citizens beheaded by IS in Libya, is one Arab country urging action.

Still, as with Iraq and Syria, Libya’s underlying problems need to be solved alongside any military action. In theory that should be easier in Libya: there is not much ideological difference between the various factions. Mr León describes this as the “very last moment” for Libyans to come together. Alas, many ordinary Libyans gave up on their country a while ago.