Date: Fri, 23 May 2014 00:13:17 +0200

May Awakening: South Sudan famine raises memories of 1998 - By Michael

Medley

Posted on

<http://africanarguments.org/2014/05/22/may-awakening-south-sudan-famine-and

-parallels-with-1998-by-michael-medley/> May 22, 2014

Warnings of a looming famine begin early in the year, and intensify quickly.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to flee their homes; many

are urban-dwellers, displaced into already-impoverished rural areas and

overcrowded relief centres. Relief agencies which for years have been

ministering to quieter hardship and more confined emergencies are wondering

whether and how to scale up their capabilities. They probably ought to be

recruiting many more staff, training and integrating them, buying extra

equipment, and loading larger quantities of relief into that frustratingly

long pipeline. But little of this can be done yet, as they still lack enough

money - or solid promises of future money - to justify the investment.

Most of the big donor states have made a preliminary contribution to the

current inter-agency humanitarian appeal, but they desire more clarity about

the situation before taking a bigger step. They realize that the recent

fighting will have disrupted many people's livelihoods, but also know that

people have various ways of coping with adversity which can absorb some of

the shock. Just how much of the shock they can absorb never seems to get

very clear.

Then there are the questions of whether the field agencies will really be

able to reach the needy people. The territory is huge, roads are dreadful

and the rainy season will make many impassible. Some donors are still

clinging to the hope that they can avoid having to pay massive costs of air

transportation. Money might have been saved if more relief supplies had been

pre-positioned by land earlier in the year. But in the worst-affected places

the situation has been too unsafe.

So the humanitarian agenda has featured for months in the growing efforts of

diplomats from IGAD and Western countries to broker agreement between the

warring parties. The diplomacy reaches a climax in early May with a visit to

the region by the Secretary-General of the United Nations. An apparent

breakthrough on humanitarian access is achieved.

It is May 1998 and it is May 2014. What happens next? Before trying to

answer this question, I will differentiate the two episodes. Although there

are remarkable parallels and echoes between the early stages of the 1998 and

(prospective) 2014 famines, the differences are important.

The unfolding of the 1998 famine

In 1998 the famine would take place mainly in greater Bahr al-Ghazal.

Certainly the disaster - then as now - was largely war-induced, but the

principal warring parties at that time were the Government of Sudan (GOS)

and the main rebel group in southern Sudan, the SPLM/A. They had been

fighting for about 15 years. In the northern part of Bahr al-Ghazal, GOS had

long sponsored various militias which mounted periodic raids on civilian as

well as military targets, killing and abducting, stealing cattle and grain,

destroying homes and crops.

Looking back from 2014 it might seem surprising that famine was not a

continual state of affairs in the mid-1990s. There was almost no infusion of

government salaries into the rural areas through soldiers, teachers and

other civil servants. Trade for the importation of extra food, agricultural

supplies and other goods was extremely limited. International aid agencies

sprinkled relief, but on a much smaller scale than was to be the case in the

post-war years. Aid mostly had to reach Bahr al-Ghazal by air. The 1998

Consolidated Appeal put the food aid target for Southern Sudan at 49,000

tonnes. (By comparison: the requirement of the World Food Programme (WFP) in

2013 was 225,000 tonnes.)

Three shocks tipped chronic deprivation onto a path which led to overt

famine. One was unusually poor weather during the growing season in 1997.

The erratic rainfall that year has been attributed an unusually strong El

Nino effect in global climate (an event which many scientists fear will

recur this year). A second factor was military. 1997 had seen a remarkable

string of success for the SPLA as, assisted by Museveni's Uganda, its major

attack force moved northwards on the west side of the Nile, capturing many

towns including Kaya, Yei, Mundri, Rumbek, Tonj, Warrap and Yirol. These

were points of external supply from which resources had diffused into the

local economy: a benefit now lost. At the same time, the increased presence

of SPLA troops in Bahr al-Ghazal meant heavier taxation of food from

villagers there. But the most important shock was a mass displacement event.

An unsuccessful rebel attempt to capture Wau resulted in as many as 100,000

people fleeing from the environs of the town into rural areas. Many from

this group would die in the famine, as would many elderly people and young

children of single mothers who under conditions of stress had become

relatively detached from the supportive relationships of kin and community.

By May 1998, displaced and desperate people had begun camping at airstrip

locations where food was known occasionally to be distributed. These places

became 'relief magnets': their reputation for food distributions attracted

the needy, the needy attracted more relief and more aid agency workers, and

the quantities of all three spiraled upwards. Aid workers were very

conscious of the dangers of this clustering: the creation of unsanitary and

overcrowded settlements where disease would spread easily, tensions become

acute with the pre-existing local community over access to land and other

resources, and concentration of supplies facilitate their taxation and other

forms of capture by local authorities and armed forces. But the dynamic

quickly became too strong to reverse.

In one way the 'relief magnet' effect was conducive to the aid effort. It

created centres of acute suffering from where journalists could conveniently

file shocking reports, belatedly pumping up public pressure for more donor

funding. In the end the 1998 Consolidated Appeal target was greatly exceeded

and more food was delivered to some locations than could usefully be

distributed. But meantime tens of thousands of people had died from

hunger-related causes.

Why didn't the relief operation get going early enough to forestall the

worst of these effects? Donors were unconvinced of the seriousness of the

threat and the feasibility of the response until too late (and the lag

between donation and relief is several months). But conviction about these

matters is not a purely rational process: it is bound up with political

commitments and ideas engrained in organizational thinking about what is

realistic and what is not. In 1998 the US - always the main source of food

aid - held back from any large donation until the end of April. I believe

this was at root due to a priority of geo-strategy.

Political background of famine relief in 1998

The US had added Sudan to its list of state sponsors of terrorism in 1993,

and since 1995 had been supporting an alliance of 'frontline states' opposed

to a spread of jihadism in the region. These states - Eritrea, Ethiopia,

Uganda and also Rwanda - more or less discreetly backed the SPLM/A in its

war against the regime of President Bashir. The SPLM/A's spectacular gains

in 1997, helped by Uganda in particular, served to intensify the pressure on

Khartoum. Visits to East Africa by US State Secretary Albright in December

1997 and President Clinton himself in March 1998 sought to consolidate the

alliance to 'isolate' the Sudanese regime and, it appeared, to further

increase support for the SPLM/A and other Sudanese opposition groups with a

view to bringing about regime change.

Faced with this threat, GOS in early 1998 was seeking international support

for a ceasefire in southern Sudan. It made its appeal especially to the UN

and European states, which tended to be uncomfortable with the belligerence

of the US approach.

The question of the ceasefire was closely linked with the growing problem of

humanitarian access. Most of the aid agencies working in the rebel-held

areas did so under the auspices of a negotiated access agreement bound by

the principle of humanitarian neutrality and supervised by the UN. The

arrangement was called Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS). Under OLS, GOS

reserved the right to approve all aircraft and flight timetables.

The vast majority of relief for greater Bahr al-Ghazal had to be transported

by air. But after the attack on Wau in the first days of 1998, GOS had

imposed a flight ban in the name of security. European diplomats moved to

and fro, and the flight ban was gradually modified during the following

months, albeit hedged with bureaucratic complications. It remained an

apparent obstacle to adequate relief operations through the months of

increasing desperation until early May when UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan

brokered the crucial access agreement. In effect, Khartoum used its

authority over humanitarian access as a resource in negotiations in order to

reach a ceasefire or - what was just as useful from its point of view - the

rainy season and a full-blown humanitarian crisis amid which international

toleration of further major SPLA attacks was unthinkable.

Conversely for the US, the eventual unavoidability of a major UN-based

relief operation frustrated its proxy-war strategy. After television

pictures of incipient famine began appearing in the world media (which had

happened by mid-April) a meeting of President Clinton with his National

Security Advisor and Secretaries of State and Defence made the decision to

change tack. USAID announced its first major donation to the World Food

Programme while Kofi Annan was arranging the key access agreement.

Although this real-political decision was, I believe, the main determining

factor in the timing of the relief operation, the fact was largely obscured

by indignation expressed in the media over the perceived inhumanity of

Khartoum and impotence of the UN. Attention was also diverted by debates

over the reliability of the famine warnings and - less sensibly but more

passionately - the appropriateness of using the word 'famine'. Certain aid

agency departments and staff had invested heavily in developing their

expertise as measurers of food insecurity and specialists in food aid

policy. Conscious also of the post-cold-war flourish of literature on the

unintended consequences of relief - and probably influenced too by donor

views of what constituted 'realistic' amounts of aid - some of the experts

attempted to use their intellectual prestige to belittle the early cries of

'famine!' (while agreeing that there was a looming crisis of food security).

'Not famine yet' remained the stance of UN agencies as long as two months

after the international press had begun showing pictures of emaciated

bodies. This became a spicy topic for public controversy, especially in the

UK.

Reconfiguration in 2014

By July 1998 more than a hundred people were dying malnourished on an

average day among the 18,000 or so gathered at the aid magnet location of

Ajiep. The horrors of starvation were also being experienced at many other

relief centres throughout Bahr al-Ghazal. Back to the future in May 2014 we

may wonder if we are heading so soon for scenes like this. Nobody really

knows, but nobody should be confident that we are not.

True, 2014 seems to have some significant advantages. In 1998 the people of

Bahr al-Ghazal had been living on the edge of survival in a war zone for

years. Many were down to a minimal level of household assets and bodily

strength even before the shocks of 1997 and the Wau exodus. Before December

2013, on the other hand, South Sudan had been largely at peace for a decade.

Even the parts of Jonglei worst affected by regional conflict still felt

benefit from networks of trade and salary-remittance. However, the matter of

people's resilience is doubtless not as simple as this. It may be that

people who have become used to a peacetime lifestyle find it harder to

manage during the return of wartime conditions.

Then again, 2014 has in place a stronger network of humanitarian agencies,

notably including UNMISS, the UN peacekeeping force. The camps protected by

UNMISS have already saved thousands from violent death. But as the

experiences of 1998 and many other disasters remind us, camps will turn into

hells. In some places they have already done so: scenes of dire food

shortage, conflict between groups within them and with local communities

outside, appalling sanitary conditions and now an outbreak of cholera. Worse

is likely to come as their numbers swell. It is illusory to think that even

with the help of UNMISS anyone will be able to run them tidily.

As in 1998 the agencies hope to reduce the clustering of desperate

populations by arranging quick singular relief distributions in remote

areas. Compared with the war years, the road network provides a more

realistic option for transporting relief, but it is nevertheless highly

treacherous in the rainy season even on major routes. In 2014 the

most-affected states are more readily reached by barge transport than they

were when the epicentre of disaster was in Bahr al-Ghazal. But road and

barge are mainly useful for transporting supplies to the major centres. They

cannot reach the majority of villages, especially not if insecurity remains

a problem. Widespread air-dropping will have to be used for that.

The success of relief distributions, especially in remote areas, will be

sensitive to the attitudes of local leaders and military units. 1998

suggests that it will often be delusory and counter-productive to target

exclusively the 'most vulnerable' within communities. If such distributions

take place, the goods are likely to be forcibly re-distributed afterwards.

Many of those who died in 1998 were people who lacked the right family or

clan relationships within the informal distribution systems. Relief agencies

must try to understand who these people are, and help them with special

measures, but within the context of broader distributions. It is not easy to

do. Meanwhile, unless some alternative way is found of paying and feeding

SPLM/A-IO, White Army, and other rebel fighters, they will almost inevitably

take much of the relief in their areas. Perhaps some units of the

government's SPLA will do the same.

This thought leads to reflection on the difficult relationship between the

relief operation and both the peace process and the agenda of bringing war

criminals to account for their crimes. The relief operation must adopt the

ideals of neutrality but will not be neutral in effect. Even if UNMISS were

fully funded and given a strong mandate to protect relief, the aid agencies

would still often rely on labour and systems owned by local oligarchs and

security conditions determined by nearby fighters. Maintaining the

cooperation of these actors is likely to depend continuously on their

attitudes to the higher political process and the tactics of the top leaders

at the negotiating tables. The existence of the relief operation increases

the pressure on the international community to ensure that the SPLM-IO is

treated as a legitimate party in the talks, and it is hostage (in some sense

at least) to war criminals who may feel under threat.

The side-effects of the humanitarian imperative understandably create doubts

about the whole enterprise in both donor and recipient countries. My

impression is that public attitudes have gained in maturity over the last 16

years, by familiarity with many hard examples. The shock when the gulf is

revealed between the ideals and the practicalities of relief in complex

emergencies is now less frequently one of mere indignation or despair. Some

may reasonably argue that the big famine intervention is a pattern in global

power that we should resist. But I for one will welcome a large increase in

relief funding following the Oslo donor conference on 20th May. On the model

of 1998 I then expect an agonizingly slow gear-up of agency operations

followed by a frenzy in which they are falling over each other, patently

failing to help many thousands of people, and yet helping some.

It should have started earlier. The rainy season is now upon us. The donors

have supplied less than half of what the field agencies requested for the

first six months of the year. They - and we - should have thought harder

about the risks. Our imaginations have perhaps been too full with the

political and military manoeuvres, and with our outrage at the perpetrators

of unspeakable cruelties. The mind's eye should have followed more intently

all the people who had left their homes.

Michael Medley is editor of <http://www.southsudancivics.info/>

SouthSudanCivics.info. Much of the above article is based on his doctoral

thesis, Humanitarian parsimony in Sudan: The Bahr al-Ghazal famine of 1998

(University of Bristol, 2010), which can be accessed in full

<http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.52985> here.

<http://africanarguments.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/SouthSudan1998-e1400

754366784.jpg> First Phase Digital

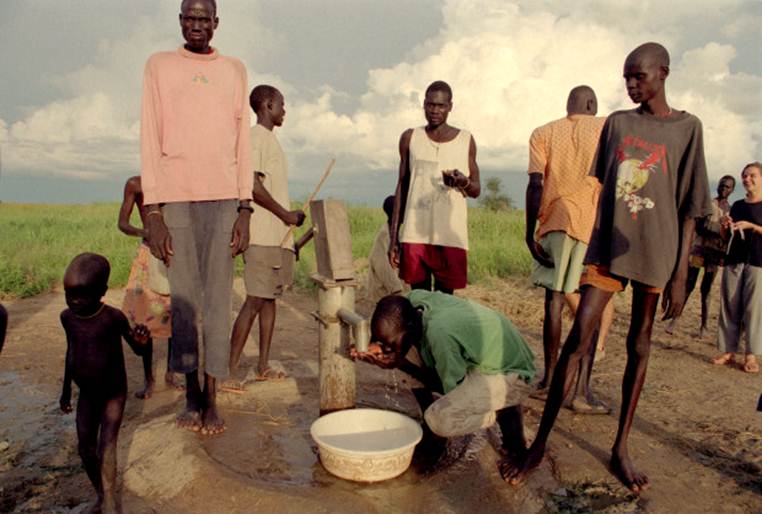

Displaced South Sudanese during the famine in 1998 (UN photo library).

(image/jpeg attachment: image001.jpg)