Date: Mon, 12 May 2014 23:11:05 +0200

Trade Misinvoicing, or How to Steal from Africa

The little-understood practice of misinvoicing or re-invoicing relies on

legal grey areas and financial secrecy and costs the continent dearly.

12 May 2014 - 2:55pm |

By <http://www.thinkafricapress.com/author/brian-leblanc> Brian LeBlanc

Lately, the media has been replete with stories about how Africa is losing

billions of dollars a year through a process called "trade misinvoicing."

The concept of trade misinvoicing is simple: companies and their agents

deliberately alter the prices of their exports and imports in order to

justify moving money out of, or into, a country illicitly.

The practice is very common in Africa. To name just a couple instances, it

has allegedly been used to

<http://thinkafricapress.com/kenya/problem-import-smuggling-secrecy-tax-have

n-shell-company-mis-invoicing> avoid paying import duties on sugar in Kenya

and to shift taxable income

<http://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/apr/17/glencore-denies-copper-tax-

allegations> out of Zambia and into tax havens abroad.

The amount Africa loses to trade misinvoicing is astounding. Global

Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington, DC-based think tank, estimates that

$286 billion worth of capital was extracted out of Africa using this process

over the past decade. Between 2002 and 2011, due to illicit financial flows,

sub-Saharan Africa lost

<http://iff.gfintegrity.org/iff2013/Illicit_Financial_Flows_from_Developing_

Countries_2002-2011-LowRes.pdf> 5.7% of it's GDP, a 20.2% increase. Of these

illicit financial flows, 62% were due to misinvoicing.

The good news is the issue of trade misinvoicing has found its way to the

forefront of development talks.

Former UN Secretary General

<http://africaprogresspanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/2013_APR_Equity_i

n_Extractives_25062013_ENG_HR.pdf> Kofi Annan, Nigerian Finance Minister

<http://thinkafricapress.com/nigeria/taxes-illicit-flows-how-can-effective-d

evelopment-co-operation-mobilise-domestic-resources> Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala,

and former South African President

<http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/157783-africa-loses-60-billion-annually-

illicit-financial-flows-mbeki.html> Thabo Mbeki are just a few African

heavyweights who have been trying to urge the international community to

begin addressing the problem of illicit financial flows and trade

misinvoicing.

It's not just "poor governance"

Whereas the impact of trade misinvoicing is becoming-- well known, exactly

how it is done is not entirely understood. This is a problem, considering

the extremely technical nature of the issue. If public policy decisions are

going to be implemented to address trade misinvoicing, a firm understanding

of its mechanics is absolutely necessary.

To start, the biggest myth associated with trade misinvoicing is that it is

entirely explained by corruption and poor governance.

Not only is this a false narrative, but it has no readily implemented

solution. It also puts the onus entirely on the country being impacted, and

fails to acknowledge the role the West plays in facilitating such

transactions.

The truth behind trade misinvoicing is that it is a two-way street. The

global shadow financial system, propped up by tax havens and financial

secrecy, is equally responsible for the propagation of trade misinvoicing in

Africa. This system of offshore banks, anonymous accounts, and

<http://thinkafricapress.com/angola/biggest-threat-tax-haven-offshore-secrec

y> shell companies is largely created by developed countries in the West.

This isn't to say corruption doesn't play a role. Yes, it may be easy in

many African countries to pay a bribe to a customs official to get them to

look the other way when a company is attempting to misinvoice a trade

transaction; however, the advent of tax havens has made this largely

unnecessary.

Why get your hands dirty when there is an easier, less-obviously-criminal

means available? To quote Raymond Baker, the President of GFI and a member

of the UNECA High Level Panel on Illicit Flows: "on-the-dock trade

misinvoicing like this simply doesn't happen."

How it works

How do companies misinvoice trade then? One of the most widely used

processes is called "re-invoicing," which sidesteps quid pro quo bribery and

corruption and utilizes legal grey areas and financial secrecy to do all the

dirty work.

Instead of defining re-invoicing myself, here is a word-for-word definition

given by a company (operating out of a tax haven) which exists specifically

to assist companies who wish to misinvoice trade. In fact, a simple Google

search of "re-invoicing" produces hundreds of results of companies openly

advertising such practices. Here is just one

<https://www.offshore-protection.com/services/offshore-reinvoicing> example:

"Re-invoicing is the use of a tax haven corporation to act as an

intermediary between an onshore business and his customers outside his home

country. The profits of this intermediary corporation and the onshore

business allow the accumulation of some, or all, profits on transactions to

be accrued to the offshore company."

In other words, companies have sent the process of trade misinvoicing

offshore. By the time the goods reach the docks, the prices have already

been manipulated. No need to pay a bribe.

The process can be extremely lucrative for the actor doing the misinvoicing.

Although the price varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, many

re-invoicing companies often only charge a 2% commission fee on the profits

shifted in such a manner. Additionally, tax haven jurisdictions generally

have little-to-no corporate taxes, which makes the proceeds from

re-invoicing tax-free. Compare that to a 35% corporate tax rate in many

African countries and you can understand the appeal of shifting capital

through re-invoicing.

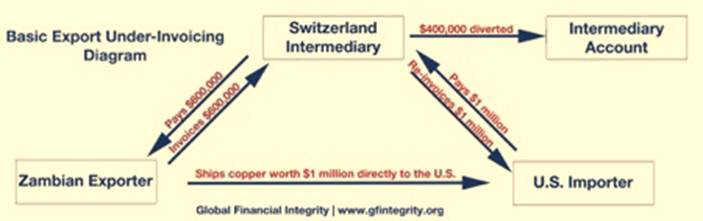

Let's assume the following scenario: imagine a hypothetical

<http://thinkafricapress.com/zambia/not-going-flow-iffs-tax-justice-copper>

Zambian exporter of copper arranges a deal with a buyer in the United States

worth $1,000,000. Now, let's assume that the Zambian company only wishes to

report $600,000 to government officials to circumvent paying mining

royalties and corporate income tax.

First, the Zambian exporter sets up a shell company in Switzerland which

(because of anonymity) cannot be traced back to him. By doing so, any

transaction the Zambian exporter conducts with the shell company will look

like trade with an unrelated party. Thus, even if the Zambian government

suspects some wrongdoing, it will be very difficult, or impossible, to tie

the Zambian exporter to the shell company in Switzerland.

Second, the exporter then uses the shell company to purchase the copper from

the exporter in Zambia for a value of $600,000, $400,000 less than the true

value of the copper. An invoice that shows receipt for the $600,000 copper

sale is then forwarded on to Zambia tax collectors.

Third, the shell company in Switzerland then re-sells the copper to the

ultimate buyer in the United States for the agreed-upon $1,000,000. The

importer is instructed to make a payment to the shell company, and the goods

are sent directly from Zambia to the United States without ever even passing

through Switzerland.

Thus, the Zambian exporter lowered its taxable revenue from $1,000,000 to

$600,000. The remaining $400,000 remains hidden in Switzerland where it is

untaxed and unutilized for development purposes. (See at the bottom

diagram):***

How to stop it

Under the international standard of the arm's-length principle, the price of

a good sold between two related parties must be comparable to what the price

the good would have been sold for had the two parties been unrelated. If

not, such as in the above example, tax and customs officials have the

authority to ignore the declared price and assess taxes and tariffs based

instead on the arm's-length price of the good. Zambia adopted the

arm's-length principle in 1999, but does that mean trade misinvoicing is a

thing of the past for the country?

Not in the slightest. Many of these transactions occur through anonymous

shell companies, hiding the fact that two companies may be related. Even if

a Zambian government official detects that a particular trade transaction is

misinvoiced, there is no way for that government official to see through a

shell company to identify its beneficial owner.

Therefore, there needs to be a multilateral effort to disclose the

beneficial owners of shell companies operating in tax haven jurisdictions.

Until then, companies will continue to hide behind them to misinvoicing

trade offshore.

Misinvoicing is not just a sharp business practice, but a way of spiriting

out of the continent billions of dollars that should be put to work in

social and economic investments. Until something is done about the network

of offshore jurisdictions and financial secrecy at a global level, Africa

will struggle far harder than it should have to in order to achieve social

and economic development.

***The following diagram helps explain the process visually:

How African Companies have "Offshored" Trade Misinvoicing

http://www.thinkafricapress.com/sites/default/files/styles/400xy/public/djib

outi-city_0.jpg

Walking through Djibouti City, capital of Djibouti. Photograph by Charles

Roffey.

(image/jpeg attachment: image005.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: image006.jpg)