A Sudanese accord-Better than nothing

A deal between the two Sudans is a first step. But a lot could still go

wrong

Oct 6th 2012 | NAIROBI | from the print edition

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20121006_MAM949.png

IN THE next few days chemicals will be pumped at high pressure along the two

oil pipelines that run northwards from landlocked, independent South Sudan

across its contested border with plain Sudan (which encompassed both

countries until a year ago) to Port Sudan on the Red Sea (see map). Known as

"warming the pipes", this step should begin to restore life to the two

Sudans' clogged economic arteries. Whether it will lead to real peace and

harmony is another question.

Nine months ago South Sudan shut down oil production in a dispute over the

fees that the north charged the south to use its export route. The two

countries nearly went to war. That threat has receded since the two

presidents signed a deal in neighbouring Ethiopia on September 27th to get

the oil flowing again. But various other differences, especially over where

to draw the border between the two countries, still dog relations. The

leaders agreed to just enough to fend off the prospect of international

sanctions that the UN Security Council had threatened to impose on whichever

side was deemed to be dragging its feet. Diplomats called it a "minimalist

deal".

The two sides did, however, agree to be separated by a demilitarised buffer

zone. It was also agreed that southerners living in the north and vice versa

will have the right to reside, work and own property on either side of the

border. As trade resumes, the rate of inflation that had begun to gallop in

both countries may now slow down.

Executives from Dar Petroleum, a Chinese-Malaysian company that is the

biggest operator in the south, where two-thirds of the Sudans' oil reserves

lie, say that production will get back to 180,000 barrels per day (b/d)

"before the end of the year". That may be optimistic. Several oilfields were

damaged by fighting that peaked between the two sides in April. Some of the

pipes may have suffered during the time they stood idle. Officials in Juba,

the south's capital, say it may take another year to restore production to

its pre-crisis level of 350,000 b/d.

A permanent border between the Sudans has yet to be drawn. Nor could the

leaders agree on the final status of Abyei, the chunk of land that straddles

an oil-rich bit of the border; the north rejected a compromise proposed by

mediators under the aegis of the African Union. The leaders also failed to

find a way of ending armed rebellions in both countries that each side

blames the other for instigating.

Optimists think the document signed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's capital, has

created enough momentum to push the two countries towards a full-scale

agreement in the next few months. Pessimists think that, after a breathing

space of three to six months, the crisis will resume as viciously as ever.

The precedents are worrying. Talks have dragged on for ten years, invariably

punctuated by rows, accusations of betrayal, fighting, and then more talks.

Abyei alone could cause a resumption of hostilities. It is the homeland of

the Dinka Ngok tribe which has links to the south. But the area is visited

for several months every year by semi-nomadic Misseriya herders from farther

north. Mediators want Abyei's residents to vote on which country they would

sooner join but the north is loth to accept this, especially if the

Misseriya herders are denied a say in the matter. In the meantime Abyei is

overseen by 4,000-plus Ethiopian peacekeepers, paid for by the UN.

Ethiopia's government is keen to get them home.

South Sudan's president, Salva Kiir, and his northern counterpart, Omar

al-Bashir, have taken to calling each other "brother", but there is little

trust between them. The north is still thought to be arming rebel militias

operating in the south's vast and volatile Jonglei state. The UN confirmed

that a white Antonov transport aircraft with false markings to make it look

like a UN plane had been seen dropping supplies in an area where a rebel

commander, David Yau Yau, has been operating. Western human-rights

organisations say that both northern and southern soldiers have committed

atrocities against civilians.

On the northern side of the border, rebellions in South Kordofan and Blue

Nile states are worsening. Mr Bashir blames South Sudan for helping old

allies from the decades-long civil war that eventually led to southern

independence. The government in Juba insists that the rebellions, in

particular by Sudan People's Liberation Army-North (SPLA-N) in South

Kordofan, are beyond its control. Since the newly agreed buffer zone may

make it harder for the south to send arms and supplies across the border,

hawks in the north may believe they have a chance to crush the rebellions.

But if the military tide were to turn against the SPLA-N there would be

fierce popular pressure on the southern government to help it

wholeheartedly. Nearly 200,000 refugees have streamed into the south.

Despite the peace deal in Ethiopia, they will not be packing to go home just

yet.

******************************************************************

Somalia and the Shabab-It's not over yet

Running liberated Kismayo will be tricky for Somalia's new government

Oct 6th 2012 | NAIROBI | from the print edition

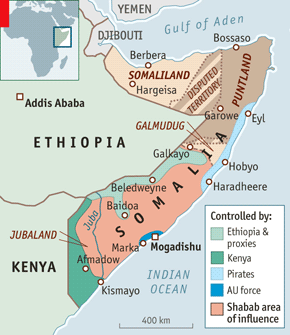

IN ITS final broadcast from Somalia's port city of Kismayo, Radio Andalus,

the mouthpiece of the jihadist group known as the Shabab, told listeners

that its fighters were withdrawing from the city to launch a guerrilla war.

With the city already surrounded by Kenyan troops and with other militias

backing Somalia's government, an amphibious assault persuaded the Shabab to

leave its last urban bastion.

After a year-long retreat, the Shabab has now abandoned nearly all the towns

it once held. Kismayo's loss denies the Shabab much of its last big source

of revenue and its main port of supply. Its fighters are now either hiding

in cities controlled by forces of the African Union (AU) or are scattered

across the countryside.

But the Shabab has been here before. Six years ago an invading Ethiopian

army swept it out of Somalia's cities. But after two years of occupation the

Ethiopians, harassed and bruised, felt obliged to leave. The last time

foreign forces landed on Somalia's beach was in 1992, when American Marines

charged in. That intervention ended in a bloody fiasco and a hasty

withdrawal just over a year later. The Shabab, who have dispersed their

communications equipment, men and weapons, can again be expected to play a

waiting game.

Taking the port city after a slow, cautious advance along heavily mined

roads may have been the easy part. Much will now depend on how the Kenyan

forces, under the AU's banner, handle Kismayo.

Kenya's first foreign war has been led by a clutch of ethnic-Somali military

men, most of whom have close ties to a single sub-clan from Somalia's

complex patchwork. Kenya's defence minister, Mohamed Yusuf Haji, and Sheikh

Ahmed Madobe, the leader of the Ras Kamboni militias, which fought alongside

the Kenyans, hail from the same clan, the Ogadeni.

When Kenya's government sent forces into Somalia late last year, one of its

aims was to set up a buffer statelet, roughly akin to the Jubaland of old,

to seal off Kenya from kidnap gangs and Islamist terrorists. Should it put

its Somali clan allies in charge of a puppet administration of Kismayo, an

ugly local backlash could ensue.

Kismayo is a mixed city. Its port and its proximity to forests, rivers and

good pastures mean that Somalia's many clans are strongly represented. So

Kismayo is both cosmopolitan and hard to govern. Some of its residents,

however much they may have disliked the Shabab, are already calling the

Kenyans "foreign invaders". Rival clan militias are primed for a fight.

"People are waiting to see what kind of administration is formed next," says

a local.

Somalia's new president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, has asked the Kenyans not to

treat Kismayo as their fief. If his request is heeded and an administration

that includes people from a range of clans is set up, the Shabab really

might fizzle out. If not, clan warlords, the bane of Somalia for decades,

may again come to the fore, with support trickling back to the Shabab.

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20121006_MAM969.png

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Fri Oct 05 2012 - 17:33:30 EDT