Militancy in Central Asia: More Than Religious Extremism

August 10, 2012 | 0900 GMT

_____

By Eugene Chausovsky

Since 2010,

<

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/central-asias-increasing-volatility>

Central Asia has become increasingly volatile, a trend many have attributed

to a rise in militant Islamism. Militancy has indeed risen since 2010, but

the notion that militant Islamists primarily are responsible for Central

Asia's volatility is shortsighted because it ignores other political and

economic dynamics at play in the region.

But if these dynamics, not jihadist designs, inspired much of the region's

recent militant activity, the impending U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in

2014 could put Central Asia at greater risk for militant Islamism in the

future. Combined with upcoming leadership changes in several Central Asian

states, the withdrawal could complicate an already complex militant

landscape in the region.

Regional Militancy: Late 1990s and Early 2000s

Central Asia was an important region for Islamist militancy in the late

1990s and early 2000s. The region is predominantly Muslim, though like all

religious practices, Islam was suppressed during the Soviet era. Given the

region's secularization under Soviet rule, many religious groups and figures

either went underground or practiced openly to the extent that the Soviets

would allow. These groups and individuals were

<

http://www.stratfor.com/geopolitical-diary/russias-ambitions-fergana-valley

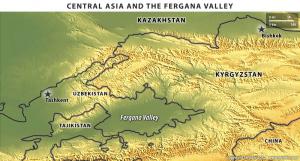

> concentrated in the Fergana Valley, the demographic core of Central Asia

that encompasses parts of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Islamists

were particularly prevalent in Uzbekistan, which is home to several

important religious and cultural cites in areas such as Samarkand and

Bukhara.

As Central Asian countries gained independence in the 1990s, religion began

to be practiced more openly, and Islamist elements operating on the margins

of society were freer to come out accordingly. This created a space in which

the Islamist environment grew stronger, just as the ability of the new

Central Asian regimes to control and suppress Islamist movements weakened.

As a result, some Islamist groups began to call for a regional caliphate

governed by Sharia.

Among these groups were the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Hizb

al-Tahrir, both of which drew inspiration from the Afghan mujahideen that

had fought the Soviet Union from 1979 to 1989. Despite their similarities --

they both advocated ousting Uzbek President Islam Karimov -- the two groups

differed in a fundamental way: Whereas the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan

used violence to further its cause, Hizb al-Tahrir did not. Other groups,

such as Akromiya, would later adopt the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan's use

of violence while espousing Hizb al-Tahrir's ideology.

Karimov clamped down on these groups in the early to mid-1990s, but the

Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan gained refuge in Tajikistan, which was

ravaged by civil war from 1992 to 1997. Because of the resultant power

vacuum and its long, porous border with Afghanistan, Tajikistan became the

primary base of operations for the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. In the

late 1990s and early 2000s, the group conducted attacks from Tajikistan

throughout the Fergana Valley and into southern Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

The 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, a country that provided both material

and ideological support to Islamist groups in Central Asia from the

ultra-conservative Taliban regime, effectively curtailed jihadist activity

and ambitions in Central Asia. With the help of the U.S. military, including

U.S. special operations forces, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan was

largely driven out of Central Asia, finding refuge in the

Afghanistan-Pakistan border area. For its part, Hizb al-Tahrir went

underground.

The Central Asian regimes, especially Karimov's, were then able to crack

down on the remaining Islamist militants. Attacks grew rarer throughout the

next decade as militant Islamist groups struggled to survive in

U.S.-occupied Afghanistan.

Militancy Since 2010

Militant attacks in the region became more frequent in June 2010, when

<

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/kyrgyzstan-eyes-turn-moscow-instability-gr

ows> clashes between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks broke out in Kyrgyzstan's

southern Fergana Valley provinces of Osh and Jalal-Abad. As a result, Kyrgyz

authorities conducted security sweeps through predominantly Uzbek

neighborhoods under the pretense of rooting out suspected militant

Islamists.

In reality, these sweeps most likely were directed at ethnic Uzbeks. Many

ethnic Kyrgyz have long been suspicious of Kyrgyzstan's ethnic Uzbeks, which

constitute a substantial portion of Osh's and Jalal-Abad's population. Thus,

security sweeps targeting these areas and the resulting armed resistance to

the sweeps do not necessarily fit neatly with the claims of religious

extremism. Rather, militant activity could be related to the internal ethnic

and political tensions between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. Indeed, these tensions

have surfaced periodically since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

A similar dynamic can be seen in Tajikistan. After the country's civil war,

reconcilable Islamist militants, such as those of the Islamic Renaissance

Party of Tajikistan, were incorporated into the government and security

forces, while the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and other jihadist elements

were suppressed. Violence peaked in the early 2000s, after which Tajikistan

experienced nearly a decade of relative calm. However, a

<

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/effects-militant-leaders-reported-death-ta

jikistan> high-profile prison break in Dushanbe in August 2010 interrupted

this calm. During the escape, about 24 prisoners deemed former Islamic

Movement of Uzbekistan members fled to the Rasht Valley in eastern

Tajikistan. This precipitated security sweeps in the Rasht Valley, which in

turn led to attacks against Tajik military convoys -- attacks that the Tajik

government blamed on Islamist militants.

These militants were much more likely linked to opposition elements from the

country's civil war rather than to jihadist militants. (That they fled to

the east is telling; those from the eastern provinces of Garm and

Gorno-Badakhshan opposed those who came to power in the western provinces of

Leninabad and Kulyab.) The jailbreak could have prompted -- or merely been a

symptom of -- the resurfacing of the political power struggle among Tajik

clans, a struggle that was commonplace during the early years of

independence. In itself, the jailbreak does not signify a jihadist

resurgence.

Moreover, the

<

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/tajikistan-launches-security-operation-res

tive-east> ongoing military operations in Gorno-Badakhshan can be seen in a

similar light. Security forces were deployed to the region after forces

loyal to warlord and former opposition leader Tolib Ayombekov allegedly

killed the region's top security officer. But Ayombekov likely did not kill

the officer out of any religious motivation. Rather, it was Ayombekov's

reported ties to the lucrative regional smuggling networks, as well as his

resistance to the regime of Emomali Rakhmon, that led to operations and

ultimately the death of the security officer. Like militancy in Kyrgyzstan,

much of the militancy in Tajikistan probably is the result of political and

ethnic rivalries, not religious extremism.

Kazakhstan likewise challenges the theory that Islamist militancy is

proliferating in the region. Given its geographic separation from the

Fergana Valley and a comparatively less religious society, Kazakhstan did

not experience Islamist militancy in the 1990s and 2000s. However,

<

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/20111220-dispatch-islamist-militancy-kazak

hstan> in 2011 Kazakhstan began seeing militant attacks for the first time

in its modern history. That the attacks were conducted with different

tactics all across the country, including Almaty, Atyrau and Taraz, is

particularly anomalous.

The Kazakh government blamed Islamist militants and religious propaganda

reportedly circulating throughout the country. However, the timing of these

attacks was curious because they came amid a growing political battle over

the succession of the country's long-serving president, Nursultan

Nazarbayev. It follows that these attacks could have been inspired less by

Islamic radicalism, which has hardly been evident in Kazakhstan over the

past 20 years, and more by the power struggle between various players

seeking to position themselves for Nazarbayev's succession.

Notably, a jihadist group called the Soldiers of the Caliphate claimed

responsibility for some of the attacks, including the October 2011 bombings

in Atyrau. The claims suggest there is a genuine militant Islamist threat in

Kazakhstan. However, the group was unknown until 2011, and there is little

information on its members and leadership.

More recently, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have seen fewer attacks and

reports of militant activity. This suggests that their respective internal

situations are relatively stable and that their governments are secure

enough to not have to use Islamic radicalism to justify their security

crackdowns.

While this is probably true for Turkmenistan, the situation is less clear in

Uzbekistan, which has been more stable than its neighbors in the Fergana

Valley. However, Uzbekistan witnessed an explosion on a rail line near the

Tajik border in November 2011. The government labeled the incident a

terrorist attack. Since the blast occurred in a remote area with relatively

little strategic significance, many speculated that the Uzbek government

conducted the attack to halt traffic and goods into Tajikistan, with which

Tashkent has had several disputes.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan is undergoing its own succession struggle, which could

result in instability. Indeed, recently there have been reports of protests

in the Fergana Valley province of Andijan, the site of a security crackdown

in 2005 that killed hundreds. In this instance again, the government blamed

the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Islamist militant elements. However,

just as in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, this was more likely the result of

power struggles within the country.

Potential Resurgence

As the dynamics and circumstances in most Central Asian countries suggest,

oftentimes it is in the government's interest to refer to any militant

activity as Islamist. Doing so suggests the activity of transnational rather

than localized political elements and gives an excuse to crack down on those

elements.

Of course, jihadist groups and elements exist in Central Asia, but most

evidence suggests that the serious jihadist players have largely been

eliminated, marginalized or pushed into the Afghanistan-Pakistan theater.

However, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan could provoke a jihadist

resurgence in the region. The security vacuum created by the departure of

U.S. and International Security Assistance Force personnel could also

destabilize Afghanistan as various internal forces compete to fill the void.

Due to Central Asia's proximity to Afghanistan and the porous and poorly

guarded border between Afghanistan and Tajikistan, there is certainly

potential for violence and instability to spill over. Particularly worrying

to Central Asian regimes are the Islamist militants in the

Afghanistan-Pakistan border area that have survived and become

battle-hardened in their war against Western forces. However, there have

been reports that Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan leader Abu Usman Adil was

killed Aug. 4 by a U.S. unmanned aerial vehicle strike in Pakistan,

suggesting that the group may be struggling to survive even in the

Afghanistan-Pakistan area.

The degree to which Islamist militant elements become active in Central Asia

again will therefore depend on the U.S. withdrawal and the state of the

Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan by that time. Until then, any developments on

the militant front in the region need to be examined within the context of

the internal power struggles and political dynamics of each country in

addition to the Islamist angle. It is only in this context that the

motivations behind militant actors and attacks in Central Asia can truly be

determined and anticipated.

<

http://www.stratfor.com/sites/default/files/main/images/Ferghana_Valley.jpg

> Central Asia and the Fergana Valley

Read more:

<

http://www.stratfor.com/weekly/militancy-central-asia-more-religious-extrem

ism#ixzz23BAfoYWf> Militancy in Central Asia: More Than Religious Extremism

| Stratfor

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Fri Aug 10 2012 - 17:01:22 EDT