Syria after the big bomb-How long can the regime last?

After the assassination of some of his closest colleagues, Syria’s

president, Bashar Assad, is staring into the abyss

Jul 24th 2012 | DAMASCUS | from the print edition

EVEN by the standards of Syrian state television, the gap between fact and

fiction yawned unusually wide on July 15th. With street battles rattling

Damascus, the capital, for the first time in Syria’s 17-month uprising, a

roaming camera crew struggled to find a picture of reassurance. “Nothing’s

happening! Its completely quiet!” a trio of veiled women shouted at the

microphone poked through their car window, as gunfire crackled in the

background. They seemed anxious to speed off, as did a lone pedestrian

waylaid on an eerily deserted boulevard, who briskly agreed that things were

“normal—very, very normal”.

In the next few days Syria’s violently flailing regime dropped all such

pretence. Even those blind and deaf to the sight of helicopters pumping

cannon-fire into residential districts north-east of the city centre, to the

whining growl of reptilian armoured cars on its ring road and the crump of

mortars in southern suburbs, could not ignore the news, on July 18th, of the

biggest blow yet to President Bashar Assad.

That morning a bomb struck a meeting of the regime’s 14-man national

security council. The dead included Daoud Rajiha, the minister of defence;

Assef Shawkat, Mr Assad’s brother-in-law, a former chief of military

intelligence and long-time key security man within the ruling family, who

was General Rajiha’s deputy; and Hassan Turkmani, a former defence minister

and éminence grise of Syria’s sprawling, 17-agency security establishment.

Several other top officials are believed to have been gravely injured, or

worse, including the interior minister and Hafez Makhlouf, a cousin of the

president notorious as the top interrogator in the state security agency and

a brother of Rami Makhlouf, the Assad clan’s billionaire chief financier.

As if the slaughter of Mr Assad’s crisis-management team were not enough,

opposition sources claimed that a remote-controlled bomb had been placed

inside the meeting room by a personal bodyguard of one of the men, helped by

other turncoats from within the nizam, as the regime is known. State media

insisted it had been a suicide-bombing, implying that it was the work of a

jihadist fanatic.

The whiff of high-level treachery fuelled rumours of a surge of desertions

by Sunni Muslims, who make up three-quarters of Syria’s increasingly

fractured sectarian mosaic. There were nastier tales of preparations for

revenge by pro-regime snipers and paramilitary gangs known as shabiha, which

are dominated by members of Mr Assad’s Alawite sect. It was more reliably

reported that helicopter gunships and artillery were firing into the largely

Sunni working-class districts south of the capital, including Palestinian

refugee camps.

If the deadly explosion and the fighting in Damascus that has persisted

since July 14th mark the start of the conflict’s end-game, most Syrians will

be relieved. Even semi-official statistics admit to 17,000 deaths so far,

with 112,000 registered as refugees abroad, 200,000 internally displaced,

and another 3m needing humanitarian aid. Foreign relief workers put the

figures much higher, reckoning that 1.5m Syrians have been displaced within

the country, with 250,000 fleeing abroad.

In the past few weeks a civil war has been growing fast in territorial

extent and ferocity. Only small parts of the country have been accessible,

and only sporadically, to outside observers. But relief workers and

displaced people in Syria point to misery and upheaval on a vast scale,

including what may be sectarian “cleansing”.

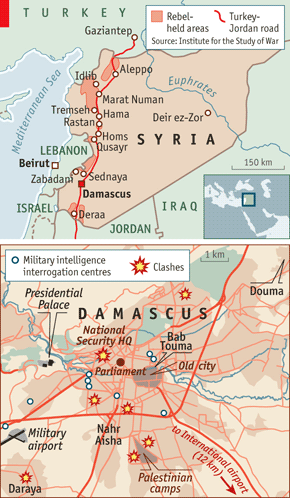

The densely populated spine of Syria that stretches 450km (280 miles) along

the main road from Jordan to Turkey has become a tattered patchwork of

combat zones from which many of the inhabitants have fled. Large towns such

as Idlib, Marat Numan, Rastan and Deraa have been gutted by months of

sporadic shelling and sniper attacks, punctuated by shabiha forays. Perhaps

two-thirds of the 1.2m inhabitants of Homs, Syria’s third city, have fled.

Surrounding villages have also been denuded; there are dismally repetitive

reports of massacre, rape and pillage.

Directed with seeming purpose against poor Sunnis, such pogroms appear aimed

at securing what had been isolated Alawite villages and districts of Homs, a

transport hub astride the strategic approach to the Alawite heartland in the

craggy mountains that fringe Syria’s Mediterranean coastline.

Far to the east, in the Euphrates valley, the large provincial city of Deir

ez-Zor has been similarly devastated, as loyalist troops have wielded heavy

weaponry, including tanks, artillery and helicopter gunships, to flush out

lightly armed opposition militiamen. A three-week assault in June wrecked

much of Douma, one of Damascus’s largest suburbs. Others, such as Daraya to

the south-west, have been ringed by loyalist forces. Shellfire and a

severing of power and telephone services suggest it may soon face a similar

onslaught.

The Damascus slum of Nahr Aisha, in the south of the city, has become a

temporary haven to hundreds of families from the stricken provinces. Seated

on the floor in the home of a local benefactor, a group of refugees from

Homs and surrounding villages recount disturbingly similar stories of

violent dispossession. “It is systematic,” says Abu Omar, still shaken, a

week after a shabiha shot his best friend dead in front of him and his

four-year-old son. “First they shell you to chase you out, then the army

goes in to loot the lightweight stuff like jewellery and mobile phones. Then

the shabiha come in, slaughter anyone who has stayed behind as well as all

the animals, including chickens. Then they steal the heavier stuff, down to

taps and doorknobs, and set houses on fire. The last wave is the Alawite

women, who carry off the fanciest bits of clothing.”

The mounting government offensive, with its increasingly indiscriminate use

of firepower, comes in response to a growing threat posed by the rebel

militias. Most of these are a local mix of defecting soldiers and

volunteers. The total manpower of this so-called Free Syrian Army may be

40,000; no one really knows. Their efficiency and equipment vary markedly.

Those that are close to smuggling routes into Turkey and Lebanon are better

armed, though they all grumble that foreign promises of weapons and cash

have rarely been fulfilled; most equipment has been bought from local arms

dealers, often purloined from army stocks, with donations from wealthy

Syrians. Abu Toni, a Damascus volunteer, reckons that in the capital there

is only one “Roosi”, or AK-47 rifle, for every three rebel fighters. These

now cost $1,500 each on the black market, a fivefold jump since the crisis

began. Reliable bullets fetch up to $2 each. This paucity of arms proved

deadly to scores of fighters in the face of an all-out army assault on the

village of Tremseh, near Hama, on July 12th, which left as many as 200 dead.

Even with meagre means the FSA has itself exacted a rising toll. Estimates

of the loyalist dead range from 3,000 to 7,000. Hit-and-run tactics account

for most of them, but in recent months FSA fighters have mounted a growing

number of carefully planned operations, including the kidnap of senior

officials in the capital, among them the businessman son of one of Mr

Assad’s closest aides. Increasingly, the rebels are relying on a network of

informers inside the nizam. “We know before they do where the army is about

to deploy, and some of the checkpoints in my district can be relied on to

let us through,” says an FSA fighter in Damascus.

Aside from defections and informers, Mr Assad’s 300,000-man army is

handicapped by the unreliability of many of its men. Although a member of

the UN observer mission reckons that loyalist forces include at least two

combat brigades that have been held in reserve, apart from fixed-wing

bombers and chemical weapons, activists report that much of the Sunni rank

and file is in effect idle. “My brother has been locked inside his base for

the past eight months,” affirms a refugee from Homs. A large

maximum-security jail at Sednaya, just north of Damascus, is widely reported

to be filled to capacity with officers suspected of aiding the rebels.

The regime’s escalation of violence has produced a backlash against it. The

influx of refugees into Damascus and Aleppo, Syria’s second city, has spread

awareness of the regime’s brutality even among households that had long

turned a blind eye to the suffering caused, according to the government’s

stubborn account, by “terrorists”. Among minority groups such as Christians,

Palestinians, Druze and Kurds, as well as the prosperous Sunni urban

merchant class, far fewer now view the state as a bulwark against extremism.

“We all know it is a criminal regime, and that they deserve what they will

get,” says an Armenian shopkeeper in Damascus’s Old City. “We would have

preferred a peaceful revolution, and we are scared of Islamist extremists,

but it is the government that has stirred all the hatred.” Prominent

Alawites, some of whom have joined the opposition, voice growing alarm at

the danger of being saddled with collective guilt for the regime’s excesses.

No one looks to the UN any more

As the military balance and popular feeling run against the government,

international diplomacy seemed increasingly irrelevant. All but the regime’s

most fervent supporters and a clutch of hopeful members of the opposition

still at large view the efforts of Kofi Annan, the UN-appointed mediator, as

doomed. Most of the exiled opposition, echoing sentiment inside the country,

have long been unwilling to negotiate with Mr Assad. Mr Annan’s mandate,

that began in April, is due to end on July 20th, though the UN Security

Council may extend it. With even Damascus now looking insecure, it is hard

to see how UN people can maintain an effective presence of any kind.

“Everything is up in the air at the moment,” conceded a UN man forlornly, in

the aftermath of the big bomb.

Only the influence of Russia, Syria’s main ally and arms supplier, has so

far insulated Mr Assad from firmer international sanction. Yet even the

Russians may begin to see their support as self-defeating. As the regime

enters what may be its death throes, it is increasingly difficult to see how

world leaders, with or without Russia, can interpose themselves to solve the

crisis.

Should the regime crumple suddenly or fall back to its Alawite heartland,

Syria’s divided opposition will have a hard time picking up the pieces. Many

hope the end will come swiftly. Some are preparing for the worst, fearing a

spree of lawlessness, as in Baghdad after its fall in 2003. “We are putting

together a unit to protect the national museum, the central bank and

especially Alawite districts against revenge attacks,” says a rebel in

Damascus. “There is still no shortage of volunteers even for that, thank

God.”

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20120721_MAM952.png

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Tue Jul 24 2012 - 17:58:43 EDT