The crisis in Syria-The tide begins to turn

Diplomacy is being overtaken by the armed struggle. But on both scores,

Syria's embattled president, Bashar Assad, is steadily losing ground

Jul 7th 2012 | BEIRUT AND CAIRO | from the print edition

SIXTEEN months into an uprising that has now left more than 15,000 Syrians

dead, the diplomatic and military pace of the conflict has become a lot

hotter. On all fronts President Bashar Assad is losing ground. No one knows

when a tipping point may occur. But even his dwindling band of friends seems

to recognise that he is on the way out.

On the diplomatic front, buttressed by his dogged old Russian allies, Mr

Assad is still refusing to give way. Even so, he may slowly be starting to

sense defeat. "A few months ago he was in denial," says a diplomat close to

the action. "But I think he should know by now that the end is near and that

he should have to go."

On June 30th in Geneva it was agreed at a conclave of foreign ministers from

nine countries, known as the "action group", that a "transitional governing

body" should be formed "by mutual consent". The gathering included the UN

Security Council's five permanent members plus Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar and

Turkey but not Iran or Saudi Arabia, deemed so antagonistic as to cancel

each other out. The secretaries-general of the UN and the 22-country Arab

League also attended, along with the EU's foreign-affairs chief.

The Syrian opposition lamented the removal of a specific reference in the

Geneva text to Mr Assad's departure that had been in an earlier draft. But

Western diplomats insisted that even the Russians, despite their subsequent

blustering denials, implicitly accepted the principle of Mr Assad's early

exit, since it was inconceivable he could stay on in a transitional regime

if mutual consent were given. "They realise he'll have to go," says the

diplomat. "He needs some dignity. But he can't kill that many people and

remain legitimate."

Western governments, working closely with the Turks and Qataris and the Arab

League, still hope against hope that the stalled peace plan presented in

April by Kofi Annan, a former UN secretary-general, will regain some

traction. "He's still the centre of gravity," says another diplomat. "He's

the best way we have."

The Syrian opposition is sceptical and impatient. To stress its

disappointment, the Free Syrian Army (FSA), the main group of armed rebel

factions, shunned a subsequent meeting of Mr Assad's opponents in Cairo on

July 1st. The Syrian Revolution General Commission, the leading network of

political activists inside Syria, left early in a huff. The biggest such

event to date, it was intended to forge a common blueprint for the wider

opposition and to give at least the impression of unity. But the factions

from within Syria suspected that exile groups were seeking to curry favour

with foreign diplomats and donors by endorsing the Geneva plan at the

expense of the revolution that they are battling to expand back home.

The Cairo meeting did not mention the Geneva document but instead issued a

vague set of constitutional principles, along with its own plan for a

transitional government. Moreover, the intended show of unity was marred by

rows over the composition of a joint committee to follow things up.

Representatives of the Kurds, who make up around 15% of Syrians, walked out

in protest against being termed an ethnic group rather than a people, and

some left-wingers and secularists reiterated charges against the Syrian

National Council, the largest exile group, that it was dominated by

Islamists (in particular, the Muslim Brotherhood) and beholden to such

foreign backers as Turkey, Qatar and the CIA.

For his part, Mr Assad had upped the ante on June 26th by announcing for the

first time that Syria was indeed "at war", decreeing new laws to punish his

opponents (all lumped together as "terrorists"). State television broadcast

a call for soldiers to seek "martyrdom" in service to the fatherland. His

government voiced tepid approval of the Geneva plan, but as with Mr Annan's

previous plan, which it formally accepted but largely ignored in practice,

suggested that its opponents should first drop their weapons.

This is not going to happen. The military pressure against Mr Assad is

mounting. Day by day, town by town, the balance of power seesaws between the

regime's forces and its loosely organised but increasingly better-armed

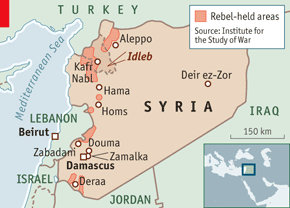

opponents. But the tide is running against Mr Assad. In the hilly

north-western province of Idleb, almost incessant shelling by government

forces has not prevented rebels from keeping de facto control over swathes

of territory, including parts of the border with Turkey which is 900km (560

miles) long.

The war is now everywhere

Fighters stroll across, ferrying in arms and medicine, and greeting refugees

and defectors passing the other way. It is reported that Syrian soldiers

patrolling the border have to be flown into some posts, since they are

unable to cross hostile territory by land. A UN expert reckons that 40% of

Syria's populated area is no longer fully under government control. The

rebels have begun to gain ground, especially in the north-west and the east.

In suburbs closer to the centres of power, the battle is also intensifying.

Mr Assad's forces have shown no mercy there. Deploying tanks, artillery and

air power, and now also routinely using spotter drones and helicopter

gunships, they have smashed parts of Douma, a Damascus suburb that has been

controlled by the opposition and is home to 300,000-plus people, most of

them Sunni Muslims increasingly disloyal to a regime dominated by the

minority Alawite sect, to which the Assad family belongs. In Zamalka,

another rebellious Damascus suburb, a bomb, widely said to have been planted

by security forces, recently killed scores of mourners at the funeral of a

rebel fighter.

Such firepower, along with thousands of arrests and the systematic use of

torture (chillingly documented in a detailed report issued on July 3rd by

Human Rights Watch, a New York-based lobby) has kept the centres of Damascus

and Aleppo, Syria's second city, broadly under regime control. Yet attacks

such as a recent bomb blast at a government ministry show that the rebels

can slip in. Even as state television showed street sweepers returning to a

"cleansed" (but also deserted) Douma, foreign journalists were being

escorted among scores of armed FSA fighters just a few miles away, casually

patrolling in full daylight.

The rebels are felling soldiers at an increasing rate, with clashes doubling

in number between March and June, the bloodiest month of the uprising so

far; in the last week of it, around 100 people were said to be dying every

day.

Many security men now move around in inconspicuous shabby cars, thanks to a

rash of assassinations, many of them in the capital. Higher-ranking

officers, including brigadiers and generals, are fleeing. Turkish officials

reported that on June 5th alone 85 military defectors crossed the border,

bringing their families along to spare them retribution.

The regime is loth to bring out of the barracks enough units to tackle all

rebellious places simultaneously, fearing defections of the Sunni bulk.

Instead, it relies increasingly on armed irregulars, many of them Alawites.

Known as shabiha, they often make up the first wave of raiders and looters

after bombardments by the army have subsided.

But though the regime's forces can take back territory at will, victories

against the rebels tend to be short-lived. FSA groups sprout again as soon

as the firefighting squads move on to bash the next rebellious town,

prolonging a game of whack-a-mole: as one insurgent pocket is squashed,

another pops up. "This is a war not for gains, but to exhaust the other

side," says Razan Zeitouneh, a lawyer in hiding in the capital, noting that

the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor, where a rebellion seemed to have been

suppressed a few months ago, is now aflame again.

Moreover, Mr Assad is also feeling the heat of a failing economy. Inflation

is running at 30% a year. The currency's value has slumped. Fuel is getting

scarce. A Western boycott of Syria's oil, 90% of which was exported to

Europe, is draining state coffers. Tourism is dead. The perception of Syria

as a pariah state is blighting international trade and commerce.

With the war spreading, the economy in trouble and diplomacy intensifying,

Mr Assad looks ever more isolated and vulnerable. Even the Russians' loyalty

may begin to wilt.

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20120707_MAM952.png

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Thu Jul 05 2012 - 18:07:04 EDT