Saudi Arabia-The long day closes

As royal heirs succumb to old age, Saudi Arabia faces an uncertain future

Jun 23rd 2012 | DAMMAM, JEDDAH AND RIYADH | from the print edition

"PRAISE be to Allah," mumbled King Abdullah as subject after subject stooped

to kiss the seated monarch's hand. The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques was

bestowing blessings on a noble deed-13 families had waived their right,

under Islamic law, to demand that the murderers of their relatives be

beheaded-amid a sombre host of robed princes and retainers. The ceremony's

reassuring timelessness was broadcast on state television.

Yet as on most evenings these days, Saudis were more likely to be glued to

their computers than to official broadcasts. Perhaps they were catching the

latest upload of "La Yekthar", one of a growing array of home-brewed comedy

shows on YouTube. That evening's ten-minute episode poked fun at, among

other things, the stodginess of state news broadcasts and the $15m cost of

fixing the toilets in a public park. Perhaps they were watching less

frivolous fare. In May an outraged young Saudi woman in the capital, Riyadh,

used her phone to film the religious police as they tried to eject her from

a mall for wearing nail polish. She then uploaded the video for all to see.

So far it has accumulated nearly 2m hits.

Life in the kingdom has always had its striking contrasts, but there is more

reason than ever for doubting that today's can long be sustained. That may

sound surprising: the pace of reform in the kingdom, it has often been said,

is inversely correlated with the price of oil. With prices coming off record

highs and enough cash in the central bank-$560 billion-to cover a full three

years of government spending things might be taken as looking stable. When a

wave of revolutions washed across north Africa last year, King Abdullah felt

no need to offer pre-emptive political concessions, as King Mohammed VI of

Morocco did. Instead, he opened the tap, pouring $130 billion into such

things as housing, education, unemployment benefits and the like, not

forgetting a little something for the pampered religious establishment. That

reversed what had been a mounting tide of complaint over poor schools,

shoddy infrastructure, capricious courts and a lack of affordable housing.

There was no Saudi spring.

The beards have all grown longer

What the royal house of Al Saud has not done, and quite possibly cannot do,

is get out ahead of the problem. "We are at a golden time, a peak," says a

prosperous stockbroker in Riyadh. "We have the resources right now to set

things right, but the problems are growing faster than moves to fix them."

Rather than the bubbly confidence that might be expected coming off the top

of an oil boom, the pervasive mood is of strained anticipation.

"We are in a sort of trance," says a businessman in the oil-industry hub of

Dammam, "waiting for biology to take its course." King Abdullah, the oldest

surviving son of Abdel Aziz bin Saud, the kingdom's founder, is at least 89.

His back problems cause him a lot of pain, which may well be heavily

medicated. His half-brother and heir, Crown Prince Sultan, who had served

for 49 years as defence minister, died last October at the age of 87. On

June 16th Sultan's replacement as next-in-line, Crown Prince Nayef, whose 37

years as interior minister had left him widely feared, also passed away.

Prince Salman (pictured a step behind King Abdullah) who took over Sultan's

lucrative defence fief last year, is now confirmed as the new heir and crown

prince. He is more than a decade younger, but has already suffered at least

one stroke. Two of his 12 sons have died prematurely of heart disease.

There are three younger brothers who might aspire to the throne, though they

do not command the same standing within the family or popular respect as the

older men: Ahmed, long Prince Nayef's deputy at the interior ministry and

now confirmed as his successor, who is believed to be in his early 70s;

Sattam, who has succeeded Salman as governor of Riyadh; and Muqrin, who

heads the intelligence services. The youngest of the three dozen legitimate

sons of Abdel Aziz, Prince Muqrin is thought to be nearing 70.

In theory the Al Saud family's secretive Allegiance Council, composed of

princes representing the lines of each of Abdel Aziz's sons, decides on

matters of succession. But, assuming that the Al Sauds can sort out among

themselves who is to rule-or, as many Saudis now grumble openly, decide how

to share future spoils-the kingdom lacks formal mechanisms to facilitate or

legitimise change, such as an elected parliament, a respected supreme court,

or an independent press. And the prestige of the Al Sauds is fading.

Rumours abound of extravagance and corruption. Infighting, too, is thought

to be rife, with powerful courtiers jostling for position. The long tenure

of older princes has ensconced rival family branches in key institutions;

each death that thins their ranks reverberates throughout the system.

Sons of Princes Sultan and Nayef hold the main posts in the ministries of

defence and interior, respectively. The National Guard, which protects oil

installations, is a purview of King Abdullah's own branch; the governorship

of the Eastern Province, a giant territory that contains nearly all the

kingdom's hydrocarbons, has been held by a son of King Fahd (Abdullah's

predecessor) for three decades. The recent reshuffle among King Abdullah's

siblings went more smoothly than many had feared; the shift to this next

generation will surely be trickier. The kingdom is now a complex, diverse

country far removed from the Al Sauds' Bedouin origins. Lineage and loyalty

cannot trump competence for ever.

"The Al Sauds' central nervous system has grown weak," says a Riyadh lawyer.

"They can respond to pain, but not to stimuli like complaints or new ideas."

Structural reforms such as granting citizens a real say in government, or

passing laws to bolster private enterprise by allowing mortgages, or opening

equity markets, are sometimes discussed, but the easier option of throwing

money at social programmes wins out. Instead of repairing old

infrastructure, the preference has been for launching huge new projects

named after the king: a giant financial centre on the outskirts of Riyadh,

industrial cities, a university, and so on.

The second pillar of the Saudi state, its stern Wahhabist clerics, is also

weaker than it was. Saudis for the most part remain fiercely attached to

their faith, and the threat from jihadist radicals, which exploded in a wave

of terrorism ten years ago, has receded. But the young, in particular, have

grown sceptical of Wahhabist injunctions that command blind obedience to

rulers. They turn instead to Salafist preachers who decry corruption (and in

some cases languish in prison) or to secret societies associated with the

Muslim Brotherhood, or to the constitutionalist movement, started by

liberals, that has a growing Islamist component-and can thus serve to import

the ideas of the Arab spring. "Our sheikhs have become a joke," scoffs a

Jeddah lawyer.

The country's 30m or so people, two-thirds of them citizens and the rest

expatriate workers or dependents, are largely complacent. Oil wealth does

drip down. But the country is not so wealthy as all that. GDP per person

remains below that of Slovenia. Middle-class households typically employ

maids and drivers, and many Saudis are indeed immensely rich. But unofficial

accounts suggest that as many as 3m Saudis, often in households headed by

divorced or widowed women, live in relative poverty. Last year three young

Saudis, Feras Boqna, Hussam al-Drewesh and Khaled al-Rasheed were detained

after posting a ten-minute film on Saudi poverty to YouTube.

The world looks just the same

With schools stressing religious indoctrination over marketable skills and

foreign labourers willing to accept wages too meagre for Saudis,

unemployment among Saudis under 30 is reckoned to be 30% or more. In the

construction industry, the ratio between average Saudi and expatriate

salaries is nine to one. Despite laws stipulating quotas for Saudi

employees, and despite a near-doubling in the number of non-government

workers, the Saudi proportion of the private-sector workforce fell from 17%

in 2000 to just 10% in 2010.

Part of last year's buy-off was the introduction of temporary unemployment

benefits, which bring 900,000 Saudis nearly $600 a month. For government

employees (all but the most menial of whom are Saudis) the minimum salary

has been raised to $850 per month, double the average private-sector wage.

Money has been poured into universities and 140,000 Saudis now study abroad

on state-backed scholarships, a tenfold increase in a decade. If foreign

education leads to jobs that may help; if it does not, the people who come

home could be a force for change.

Such spending is not sustainable. Today's bills can be met for as long as

the oil price stays above $75 a barrel, according to Jadwa Investment, a

Riyadh asset management firm (others put the number a little higher). But by

2017, Jadwa says, it will need an oil price of $100; extrapolating out to

2030 the figure is a whopping $320. Population increases are part of the

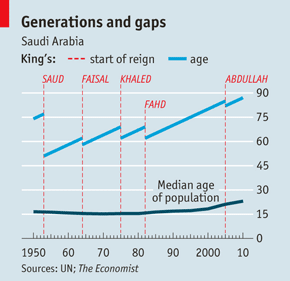

reason-the population is ageing a little (see chart) but it still grows by

1.5% a year. Another part is subsidised power. Domestic energy can be bought

at the equivalent of $10 a barrel, and at such low prices its use is rising

frighteningly fast. By 2030, says Jadwa, consumption could surge from around

3.5m barrels of oil per day at present to 6.5m if domestic prices are not

allowed to rise substantially. Less oil for export means export prices have

to be higher.

Higher prices are possible, but not certain. In the near term, low demand

may keep prices weak; and as during the oil shock of the 1970s, which made

drilling in places such as the North Sea worthwhile, recent high prices have

encouraged a surge in exploration of new hydrocarbon sources, such as tar

sands and shale oil. Traditional oilfields are also producing more. Iraq is

ramping up production, and in time Iran, Libya and Venezuela could well

surpass today's production. Saudi Arabia's output, having increased greatly

over the past decade, has reached technical limits that make further jumps

unlikely.

Oil money is not Saudi Arabia's only means of social control. Small reforms

have been used to placate dissent. More equal access to government jobs and

scholarships have dealt with some of the Shia minority's grievances. The

status of women, who may now travel and work without the permission of male

"guardians", has been marginally improved, and they have been promised the

right to vote, should meaningful elections ever be held. Their right to

drive, though, remains taboo. "It is easier to send 30,000 women abroad to

study than to let one woman drive," says a Saudi diplomat.

That which is not placated can still, for the moment, be repressed.

Human-rights activists report improved prison conditions and more systematic

application of due legal process. But despite a much-publicised programme to

release and re-educate jihadists, there are still at least 5,000 political

prisoners. Arbitrary arrest, secret trials and long periods of detention

without charge remain common. An increasing number of Saudi citizens-by some

estimates now up to 1,000-are banned from travelling. The press is

encumbered with a growing battery of rules. The majority of dissidents are

religious radicals, but vague anti-terror laws and compliant judges have

been wielded to persecute human-rights activists, women defying the ban on

driving and ordinary citizens such as Khaled al-Johani, a 42-year-old

schoolteacher who was arrested in Riyadh in March 2011, after complaining to

a BBC camera crew about limits to freedom. Mr Johani remains in prison.

Waleed Abualkhair, a young Jeddah activist, has faced a range of

intimidation tactics: trumped-up court cases; repeated interrogation;

accusations of apostasy; a travel ban. But he has not been imprisoned. He

says the authorities are careful not to provoke a backlash by acting with

excessive harshness. "We are told directly, it's a red line if you cross

from social media to the street," he explains. Yet recent months have seen a

growing number of instances where Saudis have done just that. In March,

female students in the south-western city of Abha rioted against alleged

corruption and mistreatment by university administrators. On June 6th scores

of Saudis responded to a Twitter message and joined a flash demo outside a

Riyadh shopping mall, demanding release of political prisoners. This was

brave, considering that in April a court sentenced a human-rights activist

to four years in prison for praising a similar protest held last year.

Such acts of defiance will be hard put to spread as they have elsewhere in

the region. Saudi society remains divided by clan, sect and region, and

split between religious conservatives and relative liberals. Active dissent

is confined to small groups of like-minded friends. "Things will change

[only] when the middle class as a whole demands it," reckons the Saudi

diplomat. A lawyer in Riyadh concurs. "In Egypt and Tunisia people felt both

oppression and humiliation. We have oppression, but monarchies are better at

softening the humiliation." However, he notes that everyone he knows avidly

watched Egypt's televised presidential debates, and envied them. Anger and

resentment, he says, have become "structural". If protests have not spread,

it is partly because knowing the king and his brothers are all old men

encourages a wait-and-see attitude. No one needs to act to be sure of

change; it will come of its own accord.

Whatever it is, it's named after the king

A bow for the new revolution

The Arab spring has clearly perturbed the kingdom's rulers, for whom

institutional memory is a long suit. They remember the 1960s, when Saudi

Arabia waged something like a cold war against the region's newly emerged

republics, Egypt, Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Senior princes are said to suspect

Western plotters of fomenting today's unrest. Last year Saudi Arabia sent

troops to help put down the pro-democracy uprising in neighbouring Bahrain.

Official media have highlighted bloodshed in Libya and Syria rather than

peaceful protests in Egypt, Tunisia and Yemen.

Despite talk of Saudi funding for rebels in Syria, no cash has arrived;

official clergy have discouraged even private donations. In 2011 the kingdom

withheld aid to Yemen and Egypt as a signal of displeasure, though it is

dispensing some now that it judges revolutionary fervour to have calmed. The

Al Sauds are likely to be pleased by the Egyptian generals' recent

reassertion of control (see <

http://www.economist.com/node/21557351>

article): they have yet even to recognise Libya's new government. They have

tried instead to bind the region's monarchies closer by making the Gulf

Co-operation Council a more formal union and trying, in vain, to include

Morocco and Jordan in it.

Saudi Arabia's rulers are painfully aware that, should the region's

democratic wave leave lasting change and a new order in its wake, the

kingdom will stand out as a peculiar and seemingly untenable anomaly. Even

if the wave recedes leaving nothing but a mess, it has undermined any

assumptions of rule by divine right. At the same time the kingdom's most

important alliance, with America, may face increased pressure. The United

States is no longer reliant on Saudi Arabia for more than a small fraction

of its energy needs. It has pulled out of Iraq and, soon, Afghanistan. It

abandoned Egypt's Hosni Mubarak. This raises doubts about its strategic

intentions.

Perhaps the Al Sauds will adapt to the new world they find themselves in.

But many of their own people are sceptical. The lawyer in Jeddah, his plush

office festooned with flags of the Arab spring, recalls a Koranic parable.

King Solomon, a great magician, cast a spell on the jinn and set them to

work building temples and pools. On and on they laboured, with the great man

watching over them, leaning on his staff. It was not until a lowly worm

gnawed through the staff and Solomon fell that they realised they had been

tricked: he had been dead all along.

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20120623_FBC455.png

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/p

rint-edition/20120623_FBM927.png

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Sat Jun 23 2012 - 16:37:37 EDT