Date: Fri, 12 Jul 2013 22:21:21 +0200

25 Years On: The Mixed Legacy of Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, Socialist

Soldier

After four years of Sankara's socialist policies, Burkina Faso achieved near

food self-sufficiency. Then his best friend killed him and took office.

Article | 15 October 2012 - 2:54pm | By

<http://thinkafricapress.com/author/peter-d%C3%B6rrie> Peter Dörrie

12.07.2013

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso:

“Fatherland or death, we will prevail!”

With these words, Captain Thomas Sankara proclaimed the revolution on August

4, 1983. He had just led a successful coup against the government of Burkina

Faso, back then still called Haute-Volta. His words were prophetic, for just

four years later the charismatic officer, later remembered as “Africa’s Ché

Guevara”, was murdered, shot by the men of his best friend.

But these four years were enough to make Sankara one of the most important

political figures of his time. He became one of the sharpest critics of

imperialism and celebrated leader of the non-aligned movement. His social

and economic policies, the centerpiece of his revolution, can still be

called visionary. Nothing drives this point home better than looking at

Burkina Faso today, 25 years after his death.

Unemployment, poverty and high prices

Kpénahi Traoré sits in the leafy garden of the French Cultural Institute in

Ouagadougou, the capital city. The young journalist finished university a

year ago. In this country, where only every fourth person is able to

<http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/burkina-faso/literacy-rate> read and write,

this is a real privilege. But equivalent to prosperity – or even a permanent

job – it is not. “At the beginning of our studies we were told that

journalists can make 100,000 CFA-Francs ($200) per month”, she recalls. “But

this is only possible if you work two jobs.”

The situation isn’t much different for graduates of other subjects. “It’s

not easy to find a job. Everybody takes what he can get, no matter if it

actually fits his degree or qualification”, she tells Think Africa Press.

For the great majority of the population who don’t have any school or

university degree at all, the situation is even worse. Those in the larger

towns often work seven days a week as craftsmen, mechanics or street

hawkers, without making even the official minimum wage of around $65 per

month. In the countryside, most people sill rely on subsistence agriculture.

If the rains don’t suffice, families are not able to afford school fees for

their children and girls are often married off as young as possible because

parents hope that the prospective husband can provide for the bride.

Chrysogone Zougmoré is confronted with these kinds of stories every day. The

56-year-old is the president of the largest human rights organisation of

Burkina Faso and chair of the Alliance Against the High Cost of Living. The

rising costs of living over the last years have driven many people into

poverty, he says.

Prices for the most important household goods – basic food stuffs and

natural gas for cooking and petrol – are rising constantly. Burkina Faso

relies on imports for practically all goods consumed in the country, which

makes it highly vulnerable to changes in world market prices. The little

money generated through the export of gold, cotton and sesame benefits

mostly external investors and the corrupt

<http://thinkafricapress.com/burkina-faso/rule-another-francois-blaise-compa

ore-25-years> elite.

Sankara’s social policy

This was different under Sankara, Zougmoré says: “You have to say that

social policy under Sankara was really good”. Sankara disappropriated the

country’s economic elite who controlled most of the arable land and real

estate at that time. The fields were divided between subsistence farmers and

in the cities social housing was constructed. He even declared the whole

year of 1985 rent free.

In the international sphere, Sankara aspired to a “second independence” from

the former colonial master France. He developed ties to the Soviet Union and

Cuba, which he admired for its domestic revolution. He despised development

aid, conscious of its potential to lead to dependence and external

domination.

To make Burkina Faso independent from foreign loans, Sankara tried to create

an industrial base for the dominantly agrarian Burkinabé economy. Civil

servants were forced to wear locally made clothes during office hours to

increase demand. In a move untypical for many socialist presidents, he also

supported private business, establishing special economic zones and

improving the infrastructure of the country. The programmes paid off: four

years after Sankara came to power, Burkina Faso was practically

self-sufficient in its demand for basic food stuffs. Today, the government

has to

<http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/mafap/documents/Commodity_Selection_

MAFAP_08-10.pdf> import much of its food, even in years with a good harvest.

Compaoré's cronyism and corruption

There is one individual that both Kpénahi Traoré and Chrysogone Zougmoré see

as most responsible for this change of fates: President Blaise Compaoré,

Sankara’s erstwhile best friend, mastermind of his assassination and head of

state since October 15, 1987. It was under his leadership that the current

system of corruption, cronyism and impunity was introduced that keeps

Burkina Faso from developing despite being a relatively stable and peaceful

society.

“The regime depends on corruption”, explains Zougmoré. Important

<http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2006/78721.htm> offices in the

government are given to supporters of the president. Ministers and members

of parliament use programmes for ‘agricultural development’ to chase

subsistence farmers off their land and to develop it into private estates

for sugar cane and cotton production. Gold mining – one of the country’s

biggest foreign exchange earners – is a deeply criminal business and

regularly development aid in the millions is siphoned off through corrupt

practices. One of the worst offenders for self-enrichment and cronyism is

none other than the

<http://africanarguments.org/2012/08/15/burkina-faso-blaise-compaore-and-the

-politics-of-personal-enrichment-by-peter-dorrie/> mother-in-law of the

president’s brother. The political-cum-economic elite show off its wealth

openly, zooming through the city in petrol sucking luxury cars. Under

Sankara, excesses like this were unthinkable.

“Things like corruption, embezzlement, cronyism, all that didn’t exist”,

remembers Zougmoré. “You could talk of an era of integrity. And that was the

pride of the Burkinabé. Between 1983 and 1987, the death of Sankara, we were

proud when we were abroad and said “we are Burkinabé”.”

Sankara abolished many of the privileges of the oversized government

bureaucracy. Civil servants had to donate a month’s wage every year into a

state fund. In what must still be one of the most innovative and humble

government policies of all times, he also sold off all extravagant official

vehicles. In their places, the Renault 5, the cheapest car sold in Burkina

Faso at the time, was made the official vehicle for all civil servants and

government personnel, including the president himself.

But Sankara was ahead of the times in other fields as well. His projects for

environmental protection and his literacy and vaccination campaigns were

highly innovative and mostly successful. He was especially engaged in

promoting the rights of women, leading African countries in allowing them to

join the army, banning female genital mutilation and putting women into top

government and state-owned company positions.

Today, not much remains of these reforms. His revolution followed Sankara

into the grave.

Sankara the soldier

It is tempting to put the blame for this exclusively with those who profited

from this development: the self-serving elite of the country and France,

which could re-establish its hegemonic power over Western Africa.

But the search for the culprit who condemned Burkina Faso’s experiment with

an enlightened and progressive approach to economic and social development

to failure, wouldn’t be complete without implicating Thomas Sankara himself.

Sankara’s character, like his revolution, can only be judged in shades of

grey, not black or white, explains Chrysogone Zougmoré.

Thomas Sankara lived “his” revolution to the fullest extent possible. When

the following regime tried to implicate him in embezzlement of government

funds to justify the coup, it was disappointed: Sankara’s assets at the time

of his death consisted of an average house on which he was still paying off

the mortgage, $350 in the bank and some bikes.

But at the same time, he was a soldier to his soul. It was an army

scholarship that allowed him to attend secondary school. He gained his first

political experience during a visit to an officers school in Madagascar,

where he witnessed a socialist coup d’état. Even as a president, he

continued wearing uniform and his personal sidearm.

“The regime that came into being after the coup of August 4, 1983, was a

military regime. Even though they proclaimed a revolution, they remained a

military regime with military management procedures”, explains Zougmoré, who

still judges Sankara’s legacy critically for this reason. “You had the

impression that the whole of Burkina Faso was a military barracks. There

were not any unions or youth organisations, at least no independent ones.

Committees for the Defence of the Revolution [CDRs] were imposed on

everything. There was a CDR for the youth, a CDR for women, a CDR for

farmers, CDR unions.”

A silenced majority

Independent unions had a long tradition in Burkina Faso. Many Burkinabé,

including Zougmoré, who returned from his studies in France in 1985, had

hoped for political freedoms as well as economic rights when the revolution

started. They were disappointed. When unions called for a general strike in

March 1985, a furious Sankara fired 1,300 striking civil servants and

students and replaced them with cadres loyal to the revolution. These were

ideologically educated, but often brought few qualifications for their

actual job.

Sankara and his supporters also didn’t succeed in getting the larger

population to internalise the ideals of the revolution. “He didn’t

understand that you cannot force a revolution on a population. You have to

educate the population politically before you can start a revolution”,

explains Zougmoré.

But political education in a country where the illiteracy rate even today is

at over 70% and where the majority of the population can only be reached via

poor dirt roads is next to impossible. The change Sankara tried to implement

ended up being too fast and radical for many people.

This was exemplified in his attempt to wrest power away from the traditional

rulers of Burkina Faso. Especially in the countryside, this highly

hierarchic system of kings and chefs de terre still wields tremendous

influence.

“In Sankara’s conception, the traditional rulers were a source of

stultification. They didn’t allow the populace to liberate itself and

comprehend the world”, says Zougmoré. “But he didn’t realise that the

influence of these rulers was real, that you couldn’t just decapitate the

system.” Instead, he made enemies out of this powerful elite and its

supporters.

This was similar in the international sphere. He received acclamation from

leftist circles for his rhetorically brilliant bashing of imperialism. And

he became the hero of the pan-African movement, because he clashed with the

governments of neighbouring countries, which he denounced as kleptocratic

and subservient to French political interests. But he was never able (or did

not want) to convert this clout into real international influence.

That made it easy for his enemies to agitate against him. The deadly shots

by Compaoré’s men and the announcement of a “rectification” of the

revolution did not produce any appreciable resistance in Burkina Faso.

A country at a crossroads

Today, a quarter of a century later, Burkina Faso is at a crossroads. “The

country is finished and without any perspective”, sighs Chrysogone Zougmoré.

Despite its relative political stability, it is still one of the ten least

developed countries in the world (with most of the other nine having

experienced internal conflict during the last 15 years). The president and

his entourage have enriched themselves during a time of mass privatisations

while the rest of the country stagnated.

“They don’t seem to care”, marvels Kpénahi Traoré. “If the government

doesn’t take care, this will lead to an explosion.” Both Kpénahi Traoré and

Chrysogone Zougmoré agree that if this explosion happens, it will likely

come in 2015, the year of the next presidential election. The constitution

does not allow President Compaoré to stand for another term. If he tries to

change this, or, as many suspect, tries to install his brother François,

there will be resistance.

“The population has to mobilise to bring a bit of movement into the affair

and to inject new breath into democracy”, says Zougmoré. “Burkina needs a

profound change.”

If you talk to young Burkinabé about this change, they mention the name of

Thomas Sankara. 25 years after his death, he has become an idol to many who

never experienced his rule personally. Maybe his legacy will soon inspire

the next revolution in Burkina Faso. If so, let’s hope that the

revolutionaries of tomorrow also learn from his mistakes.

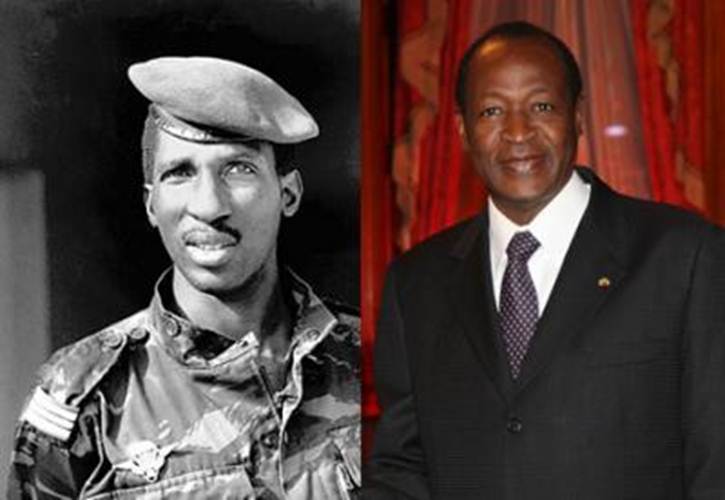

Beschreibung:

http://thinkafricapress.com/sites/default/files/styles/400xy/public/thomas-s

ankara_0.jpg

Thomas Sankara (left) was killed in 1987 on the orders of Blaise Compaore

(right) who has been president ever since. Photographs by Wikipedia and UK

Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

(image/jpeg attachment: image001.jpg)