Date: Fri, 31 May 2013 00:30:31 +0200

Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda-Pipeline poker

East Africa is in danger of throwing away part of its new-found oil wealth

May 30th 2013 | KAMPALA | <http://www.economist.com/printedition/2013-05-25>

>From the print edition

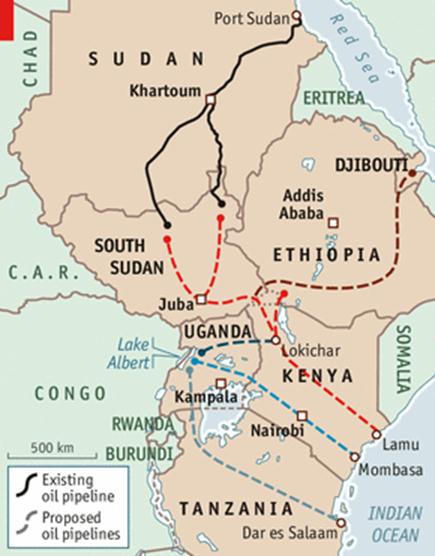

IN MARCH last year the heads of state of Kenya, Ethiopia and South Sudan met

among mangroves in Lamu, a Kenyan town on the Indian Ocean, to launch the

construction of a port and oil pipeline together costing $16 billion that

would serve all their countries and vastly enrich them. Taxpayers were

billed $350,000 for the celebratory meal, according to local officials,

though it actually cost only $4,000. So far, so profitable. But little has

happened since. Plans to build the pipeline have stalled.

The absence of the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, at the launch was the

first clue that all was not well. Uganda recently found 3.5 billion barrels

of oil by Lake Albert. It should be part of any pipeline project that links

new fields in the region. Oil has also been found on the other side of the

lake, in Congo. And across the border in Kenya, exploration looks promising;

Tullow Oil, a London-listed company, says it is pumping 281 barrels per day

(b/d) from a test well. Nearby Ethiopia is exploring furiously, too. South

Sudan, which is already producing oil, hopes to find more big fields along

its border with Kenya.

So an oil bonanza is in the offing. Revenues could lift millions out of

poverty, but only if the oil can find an efficient way to market. The local

fields are expensive to tap, say experts. A single pipeline could serve them

all and would be the cheapest option, running to Lamu via Lokichar in

north-west Kenya and beyond (see map).

But the new oil nations cannot agree on a joint plan. All are obsessed with

refining crude at the expense of exporting it. South Sudan, a country

without electricity, is in the process of building not one but two small

refineries, the first taking 5,000b/d, the second 10,000. “Contracts have

been signed,” says an official in Juba, the capital. Ethiopia has even

grander plans, hoping to satisfy the fuel needs of its 83m people by

building a refinery on the South Sudanese border, absorbing about

100,000b/d. And Uganda sees itself as a petro-supplier for the entire

region. Initially it wanted to refine 180,000b/d but may scale back its plan

to 30-60,000. Only in Kenya is reason slowly taking hold. Insiders say

refinery plans for Lamu have been downsized.

Building refineries makes no sense for east Africa. It would be wasteful and

is unlikely to give countries the energy security they seek, as some of the

fields will run dry quite soon. The economies of scale in refining are vast.

Buying fuel from mega-refineries in Asia will be cheaper for a long time to

come, even if it means losing some of the profits from processing.

Even worse, the new oil states of east Africa cannot agree on where to build

their pipeline. It is possible that three will be built—or none. Leaders in

four countries insist on satisfying narrow national goals. Ethiopia is in

only the early stages of exploration, so why—its leaders ask—should they pay

for a pipeline? The answer is that other investors, mostly from Japan, will

cough up: all that is now needed is a commitment to use the pipeline if oil

is found.

South Sudan has productive fields farther north, plus access to an adequate

pipeline owned by Sudan, its arch-enemy. Again, why pay for a new one?

Because South Sudanese leaders would like to have an alternative outlet,

given northern hostility. Everyone knows that. But officials are dragging

their feet, since the north has just agreed to a new transit deal that will

run at least until 2016.

Separately the South Sudanese are holding talks with the Ethiopians about

building a pipeline to Djibouti rather than to Lamu, cutting out Kenya. This

would cement South Sudan’s friendship with militarily powerful Ethiopia and,

so the logic goes, strengthen its position vis-à-vis the north. However,

such a pipeline would be still more expensive, since it would cross

highlands and swamps and take longer to build. Little advance work has been

done, in contrast to the Lamu pipeline.

Uganda, too, has talked up alternative pipeline plans. Maps handed around in

Kampala, the capital, show three potential crude-export routes. In addition

to the line to Lamu, they trace one to Mombasa, farther south on the Kenyan

coast, and one to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. Both would be for exclusive

Ugandan use, since all other known fields are much farther north.

The southern pipelines would also be more expensive than the Lamu option. A

line to Mombasa, one of the world’s most congested ports, would have to

climb high mountains and require heating the oil, to keep it flowing in the

high-altitude cold; the line to Dar would be extremely long and have to

cross national parks. All this because Ugandans hate playing second fiddle

to Kenya, the regional top dog.

The Lamu pipeline makes the most economic sense for all involved. But

failure to work together may doom it. National and personal interests trump

regional co-operation and commercial logic. In Uganda Mr Museveni is keen to

settle his legacy as the champion of a strong nation, building vast

refineries and spiting the tiresome Kenyans. South Sudan is fixated on

warding off the north at the expense—it seems—of almost everything else.

Ethiopia sees a chance to steal Kenya’s thunder, too. “It’s every guy for

himself,” says an oil executive wryly. “And I thought the private sector is

rough.” Pipeline politics makes a mockery of the East African Community, a

bloc dedicated to regional co-operation. All but one of the countries are

members or aspire to join.

Of late, a new momentum behind the oil push is being felt. The Ugandan

government is in final production talks with three oil companies. Executives

from Tullow, Total and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (better

known as CNOOC), as well as local civil servants, conferred with Mr Museveni

at his farm near the Rwandan border in late April. In June South Sudan will

finish a feasibility study for the Ethiopian pipeline to Djibouti, after

which it has said it will make a decision on export routes. “Everything is

up in the air,” says a diplomat. Kenyan and Ethiopian officials, as well as

oil-company representatives, have been scurrying to Juba to make their case.

Pagan Amun, who leads South Sudan’s talks with the north, is said to be keen

to ditch the Lamu pipeline.

Planners say it could be built in about three years, carrying either 400,000

b/d if all countries were on board, or about half that if South Sudan or

Uganda were not. Kenya’s new president, Uhuru Kenyatta, is pushing for

results. He may be especially keen in order to deflect attention from his

indictment by the International Criminal Court at The Hague. His first big

trip after taking office was to Lamu. None of his counterparts was there to

meet him.

By failing to co-operate, the new oil states are likely to waste part of

their wealth on duplicate infrastructure, building too many refineries and

pipelines. Oil can still be a curse.

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

(image/jpeg attachment: image001.jpg)