Born in Unity, South Sudan Is Torn Again

By

<

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/people/g/jeffrey_gettle

man/index.html?inline=nyt-per> JEFFREY GETTLEMAN

Published: January 13, 2012

PIBOR, South Sudan - The trail of corpses begins about 300 yards from the

corrugated metal gate of the United Nations compound and stretches for miles

into the bush.

There is an old man on his back, a young woman with her legs splayed and

skirt bunched up around her hips, and a whole family - man, woman, two

children - all facedown in the swamp grass, executed together. How many

hundreds are scattered across the savannah, nobody really knows.

South Sudan, born six months ago in

<

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/10/world/africa/10sudan.html?pagewanted=all>

great jubilation, is plunging into a vortex of violence. Bitter ethnic

tensions that had largely been shelved for the sake of achieving

independence have ruptured into a cycle of massacre and revenge that neither

the American-backed government nor the United Nations has been able to stop.

The United States and other Western countries have invested billions of

dollars in South Sudan, hoping it will overcome its deeply etched history of

poverty, violence and ethnic fault lines to emerge as a stable,

Western-friendly nation in a volatile region. Instead, heavily armed

militias the size of small armies are now marching on villages and towns

with impunity, sometimes with blatantly genocidal intent.

Eight thousand fighters just besieged this small town in the middle of a

vast expanse, razing huts, burning granaries, stealing tens of thousands of

cows and methodically killing hundreds, possibly thousands, of men, women

and children hiding in the bush.

The raiders had even broadcast their massacre plans.

"We have decided to invade Murleland and wipe out the entire Murle tribe on

the face of the earth," the attackers, from a rival ethnic group, the Nuer,

warned in a public statement.

The United Nations, which has 3,000 combat-ready

<

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/u/united_

nations/department_of_peacekeeping_operations/index.html?inline=nyt-classifi

er> peacekeepers in South Sudan, tracked the advancing fighters from

helicopters for days before the massacre and rushed in about 400 soldiers.

But the peacekeepers did not fire a single shot, saying they were greatly

outnumbered and could have easily been massacred themselves.

The attack was presaged by a fund-raising drive for the Nuer militia in the

United States - a troubling sign that behind the raiders toting Kalashnikovs

and singing war songs was an active back office half a world away. Gai Bol

Thong, a Nuer refugee in Seattle who helped write the militia's statement,

said he had led an effort to cobble together about $45,000 from South

Sudanese living abroad for the warriors' food and medicine.

"We mean what we say," he said in an interview. "We kill everybody. We are

tired of them." (He later scaled back and said he meant they would kill

Murle warriors, not civilians.)

Such ethnic clashes were unnervingly common here in 2009, before the final

push for independence. More ominous than the small-scale cattle raids that

have gone on for generations, the attacks often seemed like infantry

maneuvers, fueling accusations that northern Sudanese leaders had shipped in

arms to destabilize the south.

But southerners seemed to rally together as the historic referendum on

independence from the north drew near. The exuberance brought

reconciliation. Major ethnic clashes all but disappeared.

The respite was short lived. Fighting broke out almost immediately along the

border between north and south. Then, only a month after South Sudan

celebrated its independence last July with a new national anthem and a

countdown clock that blared "Free at Last," Murle fighters killed more than

600 Nuer villagers and abducted scores of children. That attack set this

month's massacre into motion.

The makeshift medical clinic here in Pibor now stinks of decaying flesh. It

is full of Murle children with bullet holes drilled through their limbs.

Many have trudged for days to get here, through swamps and murky rivers, and

their wounds are suppurating and gangrenous. The doctors take one look and

whisper the word: amputation.

South Sudan's government has been extremely reluctant to wade into these

feuds, because the government itself is a loosely woven tapestry of rival

ethnic groups that fought bitterly during Sudan's long civil war. The Nuer

are a crucial piece of the governing coalition, and the Lou Nuer, the

subgroup that led the raid on Pibor, supply thousands of soldiers to South

Sudan's army.

"Nuer fighting Nuer?" said a Western diplomat in South Sudan, considering

the complications of a military intervention to stop the massacre. "That

would be explosive."

The government has tried to broker peace talks between the Lou Nuer and the

Murle, but the negotiations broke down in early December, when the Murle

refused to give back abducted children. Nuer leaders then reconstituted the

White Army, a fearsome force of Nuer youths that massacred thousands during

the 1990s. "We had been begging the government to protect us from the Murle,

and they didn't," said Mr. Thong, the Nuer organizer in Seattle. The

decision was then simple, he said: "to make revenge."

The body of a man killed in a raid by Nuer fighters in Pibor. The number of

dead is far from clear. "There are bodies everywhere," a United Nations

official said.

<

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2012/01/12/world/africa/20120113-SOUTHSUDA

N.html> More Photos >

The government said it was planning a major disarmament campaign for the

area, once the rains stopped. Until then, "there's no justification for

anyone to take the law into their own hands," said South Sudan's military

spokesman, Col. Philip Aguer.

As thousands of Nuer fighters poured into Pibor on Dec. 31, United Nations

military observers watched them burn down Murle huts and then march off, in

single file lines, into the bush, where many Murle civilians were hiding.

Murle leaders have complained that they were abandoned in their hour of

need. Neither government forces nor the United Nations peacekeepers left

their posts in Pibor to protect the civilians who had fled, and it appears

that many Murle were hunted down.

Hilde F. Johnson, head of the United Nations mission in South Sudan, said

the peacekeepers had warned residents that the fighters were coming. But she

argued that the United Nations troops had little choice but to stay on the

sidelines. "Protection of civilians in the rural areas and at larger scale

would only have been possible with significantly more military capacity,"

she said.

The rampage continued until Jan. 3, but the number of dead is far from

clear. Joshua Konyi, Pibor's county commissioner and a Murle, said more than

3,000 had died. Several United Nations officials said they doubted that the

numbers were that high because so many people had fled Pibor before the

attack, but they agreed that scores, if not hundreds, were killed.

"There are bodies everywhere," said one United Nations official who was not

allowed to speak publicly. "It's a big area, so I wouldn't be surprised by

1,000."

Many survivors spoke of seeing dozens killed in front of their eyes. One

spindly Murle woman named Ngadok was shot in the leg as she fled with her

6-year-old son cinched to her back. After she fell, she said, the Nuer

raiders stood over her and executed her boy.

"I'm not thinking about anything now," she said, staring blankly at the

white canvas walls of the makeshift medical clinic. "My child is dead."

Murle fighters are regrouping and have already hit several villages, killing

dozens. And it may not be purely about revenge. The Murle survive off cows,

and Mr. Konyi said the community had lost more than 300,000.

A helicopter flies low over the savannah, about 20 miles north of Pibor, and

the emerald green grass suddenly turns white, brown and black. Down below

are cows, thousands and thousands of them, a huge mass of animals as far as

the eye can see. These are the Murle cattle, driven by thin young men who

look up quizzically at the helicopter, slowly making their way back to

Nuerland.

Enlarge This Image

<javascript:pop_me_up2('

http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2012/01/13/world/a

frica/13sudan-map.html','13sudan_map_html','width=720,height=701,scrollbars=

yes,toolbars=no,resizable=yes')>

<javascript:pop_me_up2('

http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2012/01/13/world/a

frica/13sudan-map.html','13sudan_map_html','width=720,height=701,scrollbars=

yes,toolbars=no,resizable=yes')>

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2012/01/13/world/africa/13sudan-map/13su

dan-map-articleInline.jpg

The New York Times

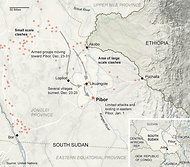

Bitter ethnic tensions have exploded across South Sudan, resulting in a

cycle of massacre and revenge.

<

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2012/01/12/world/africa/20120113-SOUTHSUDA

N.html> More Photos >

------------[ Sent via the dehai-wn mailing list by dehai.org]--------------

Received on Fri Jan 13 2012 - 16:04:16 EST